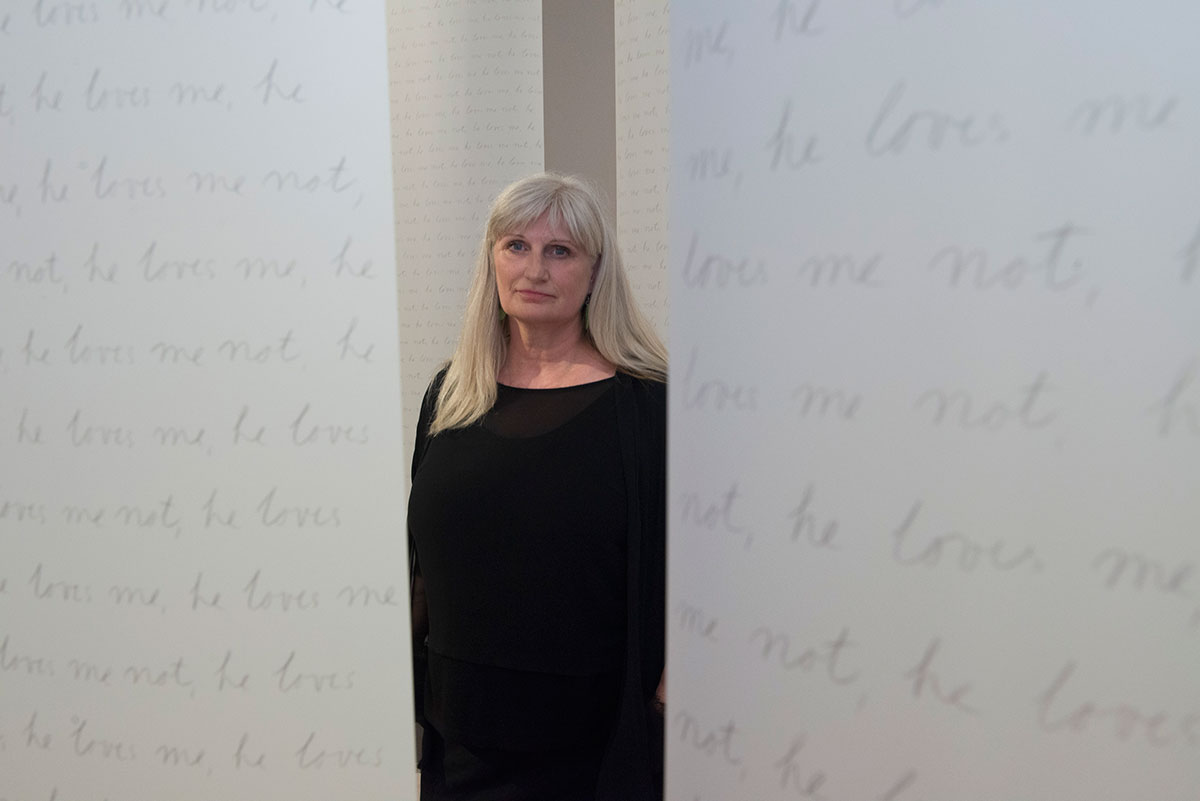

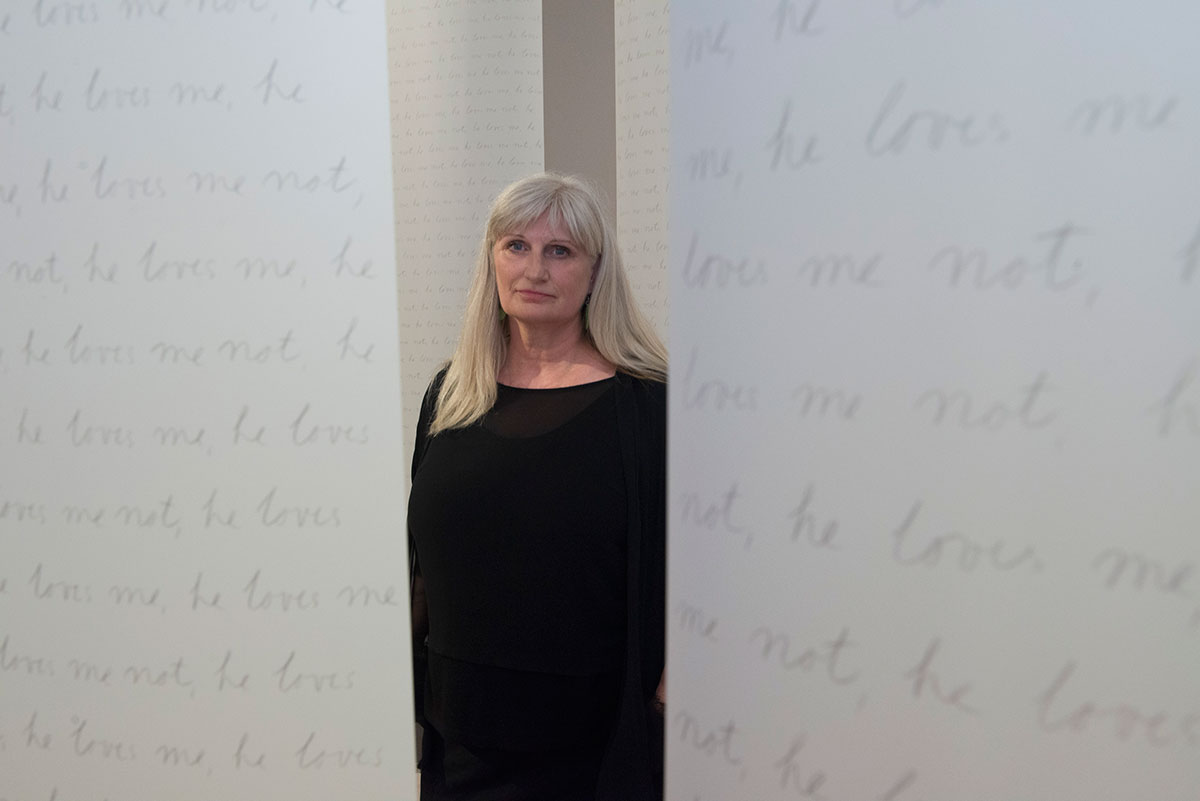

Like a Mills & Boon hero, Elizabeth Gower’s installation He loves me he loves me not commanded immediate attention. From every possible perspective, both material and theoretical, Gower’s work registered as significant. Moreover, she quietly but emphatically answered the many qualms and myths about feminism as a secondary practice in art-making: polemical, under-achieving, content with the half-baked and above all the (oppressive) mouthpiece of white middle class women of privilege. All this was achieved with the integrity of the physical presence of the highly effective and uncompromising installation in the RMIT Gallery.

As a long-term, consistently achieving contemporary artist, Gower refuses art market clichés of the irrelevance of women’s art. Without either vaginal imagery or a narrative of career and personal martyrdom, such as drove the legends of Beckett, Hester and Gentileschi, Gower challenges basic understandings of what could be seen in Australian contemporary art spaces. She brought in fabrics, light, shimmering, evanescence, the fragile and the ephemeral, paper, and modalities of making that were subtle and delicate, speaking neither of the blow torch nor the gallon-sized can of paint. Her mid-to-late-1970s works were unquestioned successes of contemporary feminism, yet never played on less-than-mainstream terms and were never sequestered from histories of abstraction and minimalism.

Gower’s works remain significant to recent art histories even as their substance increasingly is impacted by the passage of time. While she deployed fabrics, paper and softness during the era of the flourishing fibre arts movement, Gower’s formal and intellectual rigor avoided the new age modalities of its North American fairy godmothers. The clarity and logic of her works, even as they were subtle and emotionally appealing, shows up some of the limitations of certain early experimental feminist work and may suggest that Gower’s importance is global as well as national, when curators worldwide are increasingly prepared to advocate for 1970s feminism.

Within Australia, she integrated a female presence into the structures of contemporary art. She achieved many career firsts for professional women artists without any superficial trumpet-blowing or self-promotion, such as being the first woman appointed to the teaching staff of the century-old National Gallery School (part of the Victorian College of the Arts) and the first woman to become head of painting. Claiming a first that was impossible for any of her illustrious forebears (from Eugene von Guerard to John Brack), Gower even became the first pregnant lecturer at the school.

Her installation was a retrospective of sorts: we saw the play of light, of opacity, of layering, of the interaction between physically permeable ranks of modules, that shift as the gallery visitor moves between them, swaying and gently dancing with the passage of air. All these elements thread throughout many of her larger installations. It is also biographical: Gower has written the phrase “he loves me he loves me not” 21, 319 times with pencil on drafting film representing every day passed between her fifth birthday and the exhibition opening. But this work wore its history lightly, feeling and acting as contemporary. As an experienced artist, Gower is less burdened than Nolan, Boyd or Ray Crooke by the albatross or burning tyre of stereotypical expectations around the neck. He loves me he loves me not’s revival of feminist sentiments, politically based commentary, craft and the hand-led gesture or the self-contracting to a repetitious task of mountainous proportions lie entirely in the present.

Concurrently, Gower and her collaborators – gallery director Suzanne Davies and writer Helen McDonald – do not retreat from awkward politics in framing the exhibition, itself the result of long feminist-based interaction with Gower. The catalogue, whose aesthetics resonate with the restrained grace and delicacy of the installation, segues between intimate personal observation and a wide-ranging political historical overview of feminist ideas. While McDonald suggests that Gower is refusing neoliberalism’s deployment of romantic fictions behind its systematic uncharitable cruelty, Davies’ introduction quotes the artist’s observation that women are globally dependent upon the authorisation of males, either through the family or through legal-political structures.

These sentiments partly parse and rethink contemporary post-colonial arguments that ascribe male/female power disjunctions to the trauma of colonial intervention or imposition of alien value systems, or those mostly North American voices that reject feminism because visible difference exerts a more tangible oppression than does gender, and therefore female agency is sited within rather than across communities. If, as the catalogue states, “in some societies the behaviour and choices available to women are more restrictive and require cultural authorisation and consent”, and the unquestionably widespread domestic violence of settler Australia is not denied, then the increasing mutability of social structures, the unprecedented movement of people (with its upside of unprecedented cultural exchange), means that globally imbalances of female agency resonate further and in greater multiplicities in the peripheries as much as in the centres of power.