.jpg)

Richard Charles Larter was born just outside London in 1929 to upper-middle class parents, his father working in insurance. But their son rejected both their class and its accent, did his National Service in the late 1940s and then travelled around Europe and Algeria absorbing the art and ideas of that time. During schooldays, he'd attended the Saint Martin’s School of Art, and he returned there briefly to study art. 'But the place was full of squadron leaders with long moustaches drinking a great deal of beer, and it just seemed hopeless to expect to find out anything about art', he later told the National Library Oral History Collection.

Instead, he went to the socialist Toynbee Hall in the East End and spent eighteen months reproducing antique heads, never progressing to life drawing classes. 'At that point, I knew I could draw'. Dick Larter then spent the rest of his life drawing live models, mostly female and many nude, celebrating the joys of heterosexuality.

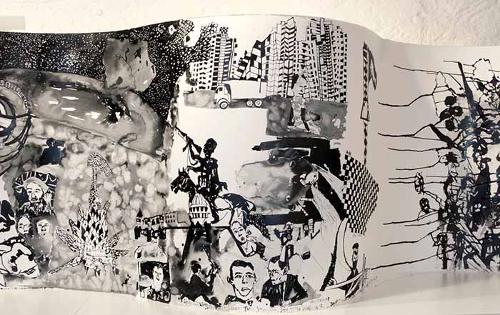

1956 was a key year for Larter’s artistic journey. Two exhibitions took place in London that would guide his future. The CIA-sponsored Modern Art in the United States, packed with New York’s finest Abstract Expressionists, engendered only his derisive response: 'Overnight, people became Abstract Expressionists with a fervour that matched converts to the Billy Graham crusade'. Meanwhile, the pioneering Whitechapel Gallery was showing the first wave of mass imagery as art, way ahead of the US. It involved Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, Victor Pasmore and Lawrence Alloway, the man who would first use the term 'Pop art’, inspiring Larter to a lifelong reuse of popular culture images from comics and newspapers, juxtaposing whores, film-stars, politicians - and Pat, the child-bride he’d got special permission to marry when she was just 17.

Patricia Holmes was his model and muse (and mother of their five children) despite tempestuous times, until her death in 1996. She was also a leading figure – better known outside Australia than within – in the Dada-inspired mail-art movement, making imagery and films with Dick’s help in the characters of the little maid, the schoolgirl and the stripper. These were then mailed around the world, 'challenging the idiot society we live in', as well as providing many of the performative poses that her husband would later immortalise on canvas.

Canvas was also a political weapon for Dick. His 1970 painting First Hand Panorama Way shows a blood-stained child’s body, photographs from Vietnam and a text addressed to ‘Dear little boy of Maylai’, regretting that 'still you died despite my best efforts' to vote, protest and dissent against the war. 'Vietnam is here in my home in my country', he concluded, and the boy’s death 'left my son to live in shame and comfort'. The young Ron Radford bought it for the collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat. Larter explained, 'By depicting evil men (including Malcolm Fraser, John Kerr and Hitler) alongside whores, pin-ups and raving beauties (who often seemed to be enjoying fellatio), I attempted to show what Hannah Arendt described as ‘the banality of evil’'.

When fellow artist Mike Brown was convicted under the Obscene and Indecent Publications Act for his exhibition Paintin' A Go Go!, Larter held a ‘non-exhibition’ at Sydney’s Watters Gallery in protest, leaving the space empty apart from picture hooks and provocative labels.

Larter also challenged the art world rule that you couldn’t be both figurative and abstract by developing a style of painting that combined lyrical abstract patterns with figurative realism. At one point he was using hypodermic syringes filled with paint to produce smooth lines of varying thickness. But the method had to be abandoned when the local chemists became suspicious of his bulk-buying habits and alerted the police.

After migration to Sydney as a teacher in 1962, he and Pat moved out to Luddenham, later Yass. After Pat’s death, Dick moved to Canberra. There he remained a prolific painter into his final decade, though his output dropped from its peak of around 400 works a year to just over 100.