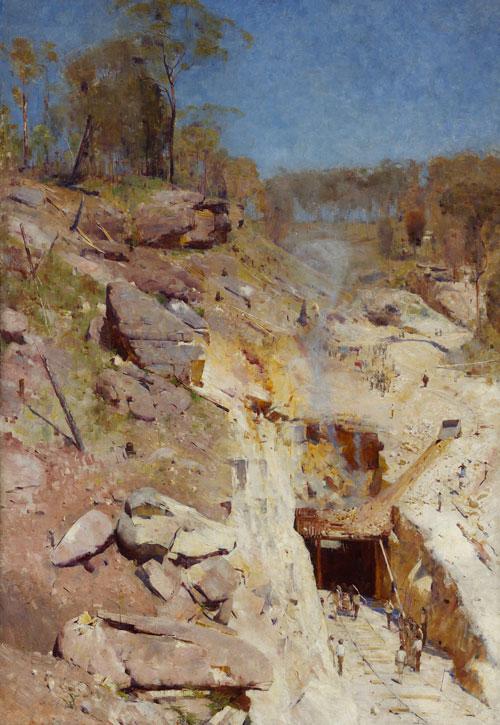

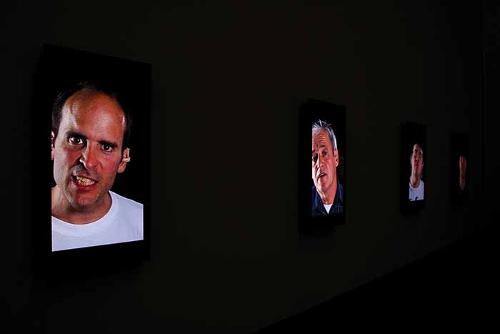

What artist takes mining as the subject of their work? Mines have featured in the iconography of art for a long time across different cultures, for different reasons. In Australia Jan Senbergs has drawn a kind of wry attention to the look of dirty industry in a bush landscape while Noel McKenna has taken a more lyrical look at the machinery and its shapes and rhythms. The work of Martin Walch in the copper mines in Tasmania narrated the toils of the men who worked those dangerous underground seams. For artists today the subject is a loaded one. Craig Walsh’s recent work in the Pilbara is dark and menacing, with the faces of elders fractured by the fissures of ancient rock faces, as around them iron ore is extracted in ever-increasing quantities for shipping overseas.

Any reference to mining now has to acknowledge that mineral extraction in Australia has reached a point where the public as a whole is uneasy at best and many people are becoming deeply worried. We have found, In curating this issue of Artlink about mining, we have found that even John Gollings’ spectacular aerial photographs of gigantic open-cut mines, seemingly captured with the objectivity of a camera at a great height, engage in this concern. What is it we are really looking at? Is this what raw money looks like? Is this exploitation beyond the pale? Mining and the price of minerals are now so precisely calibrated that an open-cut gold mine changes its form on a daily basis according to the market price of gold – as the price fluctuates so the trucks move from one section of the mine to another. When the price is high, the areas of low concentration become viable, and vice versa.[1]

Bill McKibben and his 350.org campaign to encourage institutions to divest their stocks in fossil fuel has recently drawn attention to the Galilee Basin in Queensland containing the largest unexploited thermal coal deposit in the world, which when burned will account for 7-8% of the world’s atmospheric carbon, and play a part in taking the planet past the two degrees of warming which will change human lives forever. The notion of peak oil and peak coal are now an anachronism. There is always more fossil fuel in the planet, even if whole regions and their water supplies are devastated in extreme extraction processes such as fracking. The very recent discovery of gold particles in the leaves of trees in Western Australia, with the obvious implications, are a marvellous case in point. McKibben says to prolong the Age of Coal, which has long since reached its use-by date, is lunacy. Cities around the world like Seattle, San Francisco, Portland, and 380 university campuses in the US are hearing this and acting to get rid of their stocks and shares.

Australia is in an agony of indecision about the costs and benefits of mining of fossil fuels as the same global corporations that mine thermal coal and coal seam gas also extract umpteen other minerals which of themselves do not increase global warming. Twiggy Forest (Fortesque Metals) announced a massive endowment to the University of Western Australia in October this year. Rio Tinto is wellknown in the arts as a generous sponsor of a range of exhibitions and arts projects and has in place some programs providing assistance of various types to Indigenous communities in the north of Western Australia. BHP Billiton is also a large sponsor of the arts, as is SANTOS. With arts sponsorship being so hard to obtain, who can blame the big museums for supping with the devil.

But every time a new discovery of minerals is made, further and further into the most vulnerable places remote from view, such as most recently the ocean bed of PNG, we shudder at the thought of the as-yet unknown impact of gigantic machines scouring around the volcanic vents. Fiona Hall, recently accorded the Order of Australia, has been a powerful force for the subtle understanding of ecological atrocities. On her recent sojourn as a “searider” into the Kermadec Trench, between Tonga and New Zealand, picturing these extraordinary places and creatures being obliterated, many of which we are seeing for the first time, she said: “behind my eyelids I saw red.”[2]

Footnotes