Edited by Ian McLean

Power Publications with Institute of Modern Art, 2009, 341pp, RRP $49.95

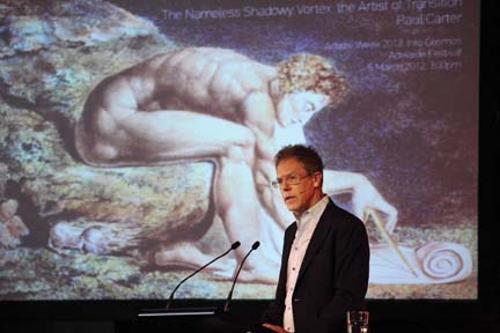

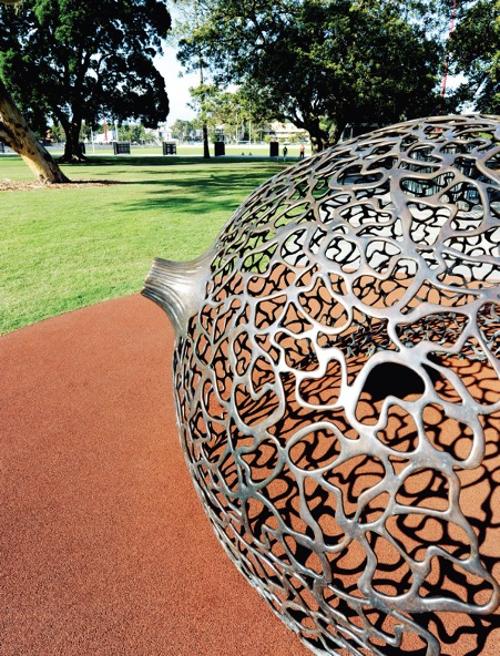

As happens every two years, Adelaide was the site of a visual arts marathon recently with the conjunction of Adelaide Festival Visual Artists' Week exhibition events at contemporary art spaces throughout the CBD and surrounds. The city centre, designed on a square mile grid, tested the physical fitness of local and visiting arts aficionados with the venues hosting Adelaide International 2012: Restless.

One suggested route could commence at the Flinders City Art Gallery in the bowels of the State Library on North Terrace before heading west on to the Anne and Gordon Samstag Museum of Art and the Australian Experimental Art Foundation at City West Campus of University of South Australia; travel parallel to West Terrace, crossing South Terrace to Parkside for the Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia; turn east back towards the city and visit Deadly: between heaven and hell at Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute on the corner of East Terrace and Grenfell Street; before turning west on North Terrace once more to Parallel Collisions, 2012 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia.

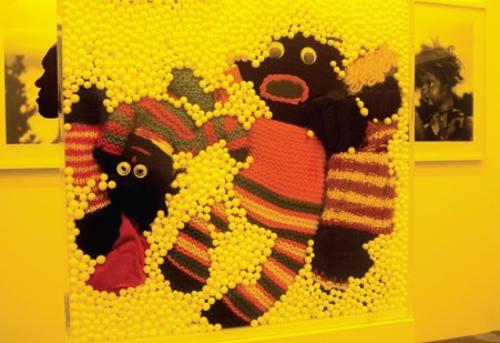

On entering the imposing colonial edifice of the state gallery, passing its soaring Palladian columns, through the front entrance of the Elder Wing, visitors were hailed by a commanding wall mural by polemicist Richard Bell, employing his customary palette referencing 20th century international art heroes such as Pollock and Johns, and closer to home, Ronnie Tjampitjinpa’s Tingari icons; bordering familiar, yet at the same time foreign images drawn from the public domain.

Solidarity (2012), daubed directly onto the stately walls behind the front desk by Aboriginal arts students who worked under the guidance of Bell during its installation, refers to a relatively unknown incident at the radical end of the 1960s where national sporting prowess collided head-on with a rising international consciousness. At the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico, Australian sprinter Peter Norman, who had won silver in the 200 metres - in a time still standing as the Australian record – stood on the dais alongside African-American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, in a stance of silent, dignified unity with Smith and Carlos as the latter each raised a black-gloved fist in the Black Power salute.

His position supporting human rights earned Norman the decades-long ire of the Australian Olympic authorities, in stark contrast with long-standing admiration from many within the US Athletics and Sporting fields. Bell’s admiration of Norman’s pacifist, humanitarian position was eloquently advocated during his artist’s talk and one can only imagine the distaste with which some conservative commentators might have viewed its provocative location. The deliberate placement of this work emphasises the fact that there is a cinder in snow’s chance of averting one’s gaze as visitors enter the hallowed halls of the state’s finest art museum.

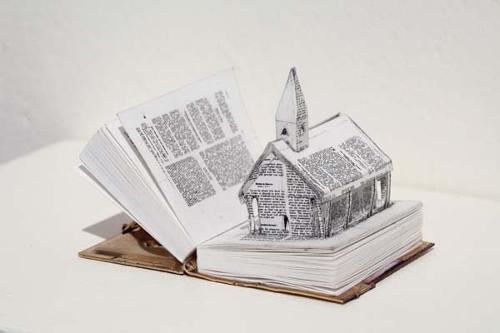

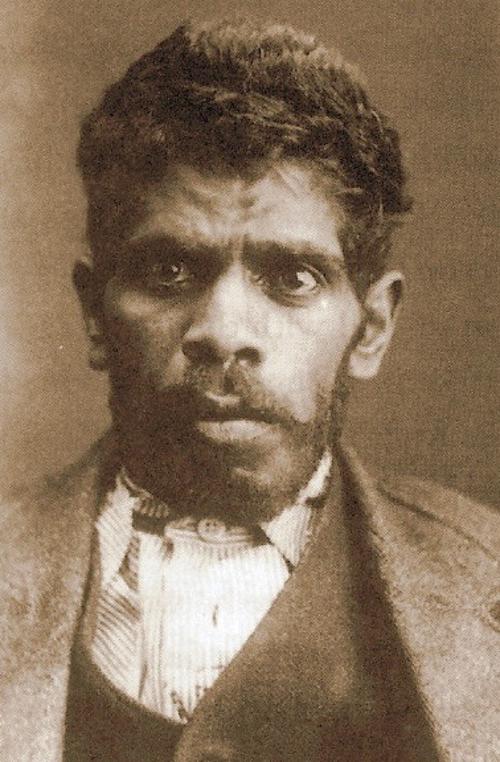

Adelaide, known as the City of Churches (less-widely appreciated for its infamous crimes throughout the 20th century), prides itself on its cultured position as the Festival State, although it has slipped from pole position in recent years due to competition from other states. Fitting then that Richard Bell, Cultural Agent Provocateur/Raconteur, has made his mark front and centre of the contrary institution that led the way in 1939 as the first public art gallery to acquire an work by an Aboriginal artist – Namatjira – as a work of art, not artifact, was the first institution to acquire works from artists of Western Desert communities in the early 1980s, yet was the last in the country to create an identified Indigenous curatorial position, shamefully as a three-year curatorial traineeship, just over 4 years ago. Astutely, the current AGSA Director, the passionate and inspired Nick Mitzevich, swiftly amended this shortly after commencing his tenure in mid 2010.

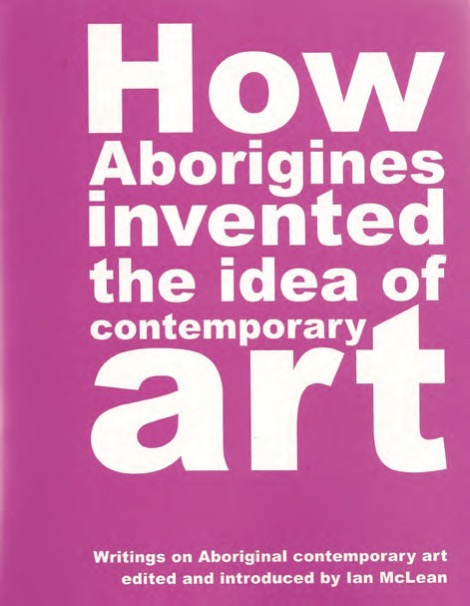

Readers may wonder what all this has to do with How Aborigines invented the idea of contemporary art, the weighty tome recently published by the Institute of Modern Art and Power Publications. Part of the series 'Australian Studies in Art and Art Theory’ this significant anthology is introduced and edited by respected academic Ian McLean, Research Professor of Australian Art at the University of Wollongong, and received assistance with publication from the Australia Council for the Arts, the Getty Foundation, and the Nelson Meers Foundation. An art historian whose specialist area is Indigenous art, McLean is perhaps best known for his comprehensive theoretical writings on the work of contemporary artist Gordon Bennett.

Cheekily, the cover is large block white text on shocking pink background – not a stippled dot or rarrk line in sight – even the ‘dot’ above the ‘I’s are square, not roundel, just to make it clear to readers that this is not another coffee table volume, nor an exhibition publication.

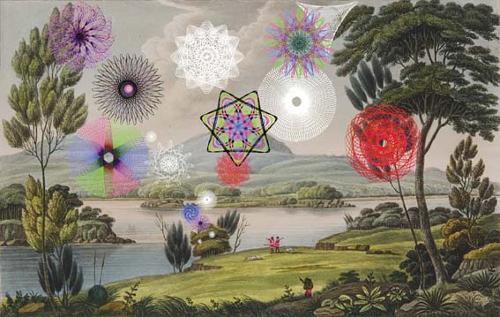

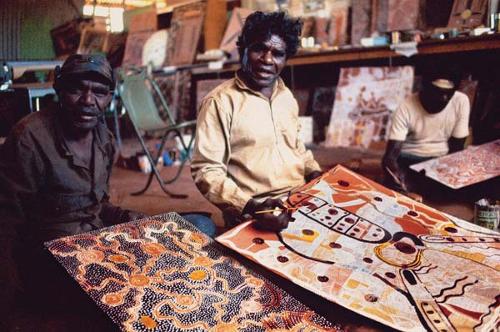

This reader loved the outer skin, though was not so certain of the choice of non-Aboriginal artist Tim Johnson as being the most appropriate for the inside frontispiece (no slight intended on the work of Mr Johnson). However, that sits with the overwhelming focus on the movement known as the Papunya Tula/Western Desert school(s) in relation to Aboriginal art being arguably considered as contemporary art.

Just as cheekily, Richard Bell is firm in his stance with what he and a number of cohorts challengingly (and to many, disrespectfully) term as ‘Oogabooga’ art. Bell is just as adamant that his work is contemporary, and that work by artists from ‘remote’, ‘traditional’ (insert ‘authentic’, ‘truthful’, ‘unadulterated’) can not be considered as contemporary. For those working as curators in the multi-disciplinary, multilayered – literally and metaphorically – cosmos of Indigenous visual expression, particularly Indigenous curators (a role with which this author has some experience), any work being created now, and in recent decades is contemporary, irrespective of the origin/domicile of the artist(s), as attested to in the writing of respected curator Hetti Perkins, "Even ‘traditional’ art is contemporary". Or to quote highly regarded artist Judy Watson: “my art is both Country and Western”.

The anthology is chronological commencing in 1945 and running through to 2007. Assembled into contextual chapters of ‘autonomous narratives’, McLean states clearly from the outset that the anthology intends to “weave a coherent – though not comprehensive – picture of the artworld’s infatuation with Aboriginal art.” This it succeeds in doing and whilst it is intriguing and incredibly useful to be able to chart the discourse and journey of the Aboriginal art industry over six decades, there are some glaring omissions, to this reader’s eye at any rate.

From the outset I declare my interest as someone who has been immersed within this sector for over a quarter century. However, the voices that appear obviously absent include those of Indigenous curators from community organisations, ethnographic and fine art museums, other than the expected inclusions of Djon Mundine and Hetti Perkins, yet even in their case they are not represented in the way one would expect, for example: Mundine’s erudite and eloquently philosophical essays from a diversity of publications (examples include They are meditating: bark paintings from the MCA’s collection (2008), The Native Born: objects and representations from Ramingining (1996); Perkins’ absence from the section on “Zones of engagement – Arnhem Land”, with little mention of the significant exhibition, Crossing country: the alchemy of western Arnhem Land art (2004), curated during her tenure at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, although the catalogue is noted (somewhat ironically) under “Aboriginal voices in Artworld Criticism”. Likewise, the "Zones" section on the Western Desert should include other voices than just those included here.

Under “Urban Australia” where is there any mention of the south-west of the country – the Carrolup child artists from Marribank, WA, of the 1940s/50s; the print-makers of the late 1980s/early 1990s, such as Sally Morgan? Where is reference to seminal exhibitions such as Koori Art ‘84 or critical discussion on the contribution of Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative and similar collectives such as proppaNOW?

In the section on “Appropriation” why no reference to respected Indigenous curator Franchesca Cubillo’s considered response to the late Elizabeth Durack’s invention Eddie Burrup? No mention under “Abroad” of either the 1990 or 1997 representations from Australia at the Venice Biennale; no reference within “Gender” that the 1997 representation at the aforementioned event included the work of three Aboriginal women artists (Emily Kam Kngwarray, Yvonne Koolmatrie and Judy Watson) and was curated by two Aboriginal women, Perkins and Croft, with the assistance of Victoria Lynn. What of the major Australian Indigenous Art Commission for the Musée du quai Branly, curated by Perkins and Croft in 2006?

Within the section “Ethics”, there is not a single Indigenous voice, despite the considerable contributions of people such as Doreen Mellor, Terri Janke, Cubillo and many others towards publications on cultural protocols for the museum and art sectors, and the 2006 Federal Inquiry into Australia’s Indigenous visual arts and craft sector.

What of the considerable role of photography within the contemporary Aboriginal art/Aboriginal contemporary art movement(s), and the extensive writings on this area by Indigenous and non-Indigenous authors? Although Nikos Papastergiardis’ lyrical essay on the work of the late Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi photographer and filmmaker Michael Riley is included?

Under “Politics” I would like to have seen reference to the critical exhibitions Tyerabarbowaryaou: I shall never become a white man, curated by Mundine and Fiona Foley for the Museum of Contemporary Art in 1992 and revised for the 1993 Havana Biennial in Cuba; and True colours: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists raise the flag, a joint initiative between Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative and the Institute for New International Visual Arts, UK, (2004); discussion of the term ‘Blak’, coined by Erub/Kuku/Mer artist Destiny Deacon, first publicly aired in her work Blak lik mi, with its clever sly nod to the 1961 publication by white American journalist, John Howard Griffin (oh, double irony!). Griffin’s non-fiction book detailed his – at the time shocking – journey through the racially segregated deep south of the USA in the late 1950s, while disguised as a Black Man.

Women artists are given short shrift, as are the considerable contributions from notable non-Aboriginal women curators, art centre co-ordinators, commercial representatives and writers. Although Judith Ryan and Margie West gain notice others that come to mind include Jenny Green, Dianne Moon, Marina Strocchi, Naomi Sharp, Karen Dayman, Beverly Knight, etc. Likewise, the “Craft vs Art” discourse is ignored, as are the artists, curators and writers associated with the Torres Strait Islands, Deacon aside.

It seems there is a distinctly Y-chromosome bent throughout the publication – sadly, the lack of input from Perkins as initial co-editor is noticeable, for although Professor Langton provided guidance, the aforesaid omissions impact on this reader’s engagement with the book – I kept hearing Perkins’ quote “Margin, a white space for black people” as the gaps became more apparent. A bibliography or further suggested reading section could have alleviated these concerns, for as the editor reiterates, he wishes most of all to provide “a portal that will encourage readers to return to the original texts.”

It may appear that I have found little to commend in this publication but that is not the case, for reconsidering many of the original texts and reading some for the first time was a fascinating experience, recalled myriad memories of the good fights that so many of my colleagues fought at the time for recognition and acceptance, and continue to do so.

At a recent conference in Alice Springs - the ‘dead heart’ of Australia to some, the birthplace of contemporary Aboriginal art/Aboriginal contemporary art movement to others – organised by advocacy agency Desart for art centres from central Australia, much of what was discussed was, frustratingly, the ‘same old, same old’, with few apparent lessons learnt from the experiences of those gone before – artists, curators, art centre co-ordinators, etc. The room seemed full of bemused ghosts, particularly the spectre of Namatjira – what, if anything, has been learnt from lessons past?

So, let us return to the raised fist of Bell, as he stands alongside Solidarity in the Art Gallery of South Australia, in the heart of venerated and cultured city of Adelaide, in the second decade of the 21st century. Even though Bell is sometimes apparently dismissive of work from ‘remote areas’ he also champions his work as part of a 21st century Dreaming, his Dreaming, others nightmares. How did Aborigines invent the idea of contemporary art? Perhaps this is simply volume #1 in an endless series on the issue and the next editor may be Indigenous – a Never-Ending Story.