Shadows are ephemeral, but the shadows of Sangeeta Sandrasegar's works linger in the mind.

Her sustained research and development of a visual language of shadows has led to 'White Picket Fences in the Clear Light of Day Cast Black Lines', an exhibition comprising one new work of the same title and some older works created between 2007 and 2009.

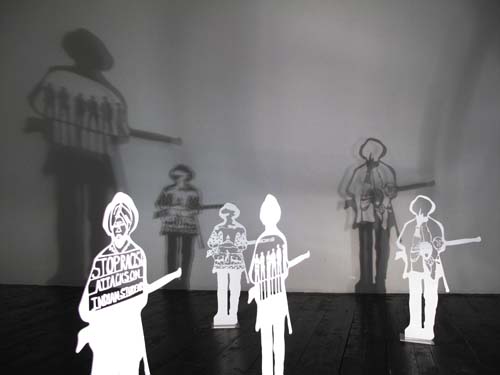

The cacophony of busy Hay Street of Sydney’s Chinatown dissipates in the dark and quiet enclave that the artist has created in the gallery. On the upper level 'White Picket Fences...' consists of two groups of two-dimensional, white acrylic sculptures of a soldier’s silhouette, standing about a half a metre tall. Lightbulbs lying alongside give the work a second dimension - or rather a second life - through the shadows cast on the pristine, white walls.

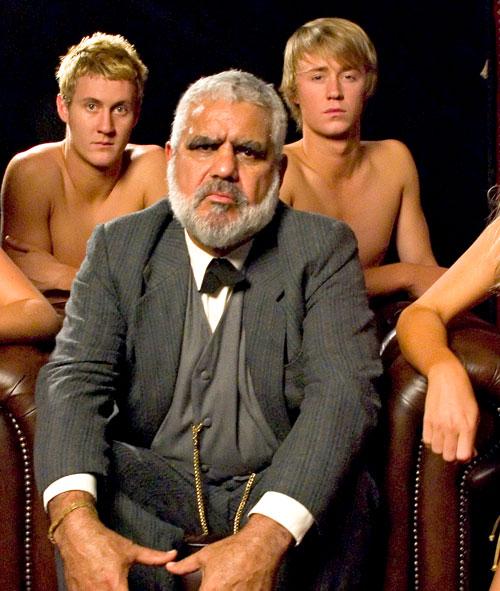

Within the silhouettes, lie a range of seemingly disconnected images - the Buddha, the Indian deity of Krishna, Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station, idyllic landscapes from miniature paintings, hennaed palms, police squads and protesters holding up placards condemning racism. And there the narrative emerges. Those who followed the frenetic media coverage of racial attacks on Indian students in Australia recently will immediately identify these images of police and protesters.

Sandrasegar was in Spain as part of an Australia Council residency when the attacks were reported. The constant bombardment of images by the media left a mark on her psyche. The hysteria is recreated for the viewer in this work through the multitude of sculptures and in turn, their many shadows. The images of the protesters and police are copied from news clips that the artist saved at the time.

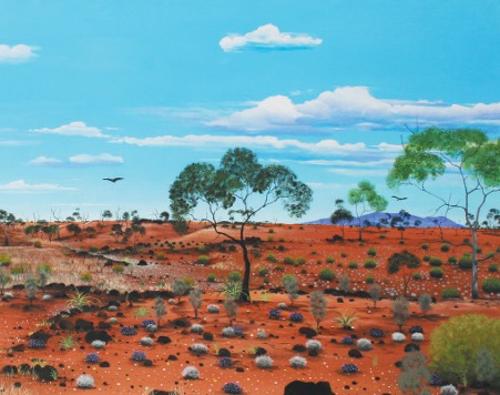

The viewer, drawn in by this part of the story, must now walk around, into and through the work, to piece together the rest of the story. Krishna is an iconic image of India and Indians, pointing towards the home of the immigrants. The idyllic landscapes - are they the homeland that the immigrants have left behind, or the new land they sought, but cannot find in Australia? The Buddha is a symbol of contemplation and looking again, and that seems to be Sandrasegar’s primary motive: to encourage viewers to reconsider the issues and read between the lines.

The title of the work introduces further layers of interpretation. White picket fences are the symbols of ideal middle class suburbia to which many Indian immigrants to Australia aspire. Picketing also has the alternate reading of protests alluding to those staged by the Indian community in Melbourne after the attacks.

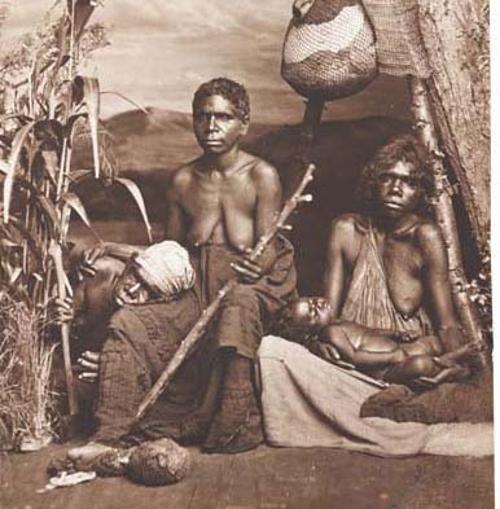

Sandrasegar says that the motif of Black Lines came to her after reading Tasmania’s history. The 'Black Lines' refer in part to the infamous period of conflict between European settlers and local indigenous inhabitants known as the Black War. During the 1820s, a human chain of male colonists convict and free was formed in northern Tasmania, in a failed attempt to move southwards for six weeks, pushing the Indigenous population into the Tasman Peninsula.

'This sounded like modern detention centres these stranded spaces in Australia that they start creating,’ she says. ‘Although we have now apologised, how we deal with people hasn’t changed whether those people were here first, or are coming in now.’

Even with the storm over the Indian student issue subsiding, debates have been raging over the ‘boat people’. For Sandrasegar this labelling of the ‘UnAustralian’ and the ‘Other’ is a continuing area of exploration.

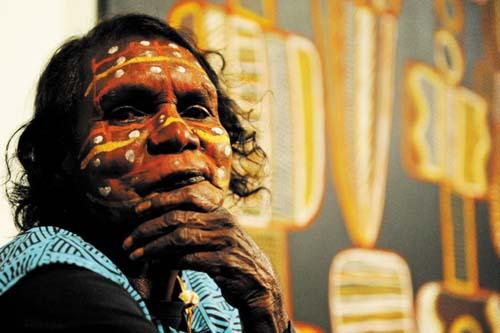

The second part of the exhibition on the lower level gives voice to other minorities - people caught on the margins of society. Among these, are three works from the series of seven, titled 'The Shadow Class', depicting the myriad forms in which slavery exists today. A carpet-weaver, a sex worker and a domestic, each one a silhouette of the artist cut out from felt and then embellished with mixed media are the Shadow Class.

Unlike her usual practice of objects that cast shadows, these works of black felt are shadows themselves - the slaves are gone, only their shadows remain.