The Metro Arts Galleries have a distinctive feel. It could be the spicy smelling floorboards, their weathered unevenness and the stillness of the air in there. It's hard to forget where you are, although easy to forget you're in the middle of the city, somewhat tucked away. The space is palpable and memorable. It casts an extra layer over the art.

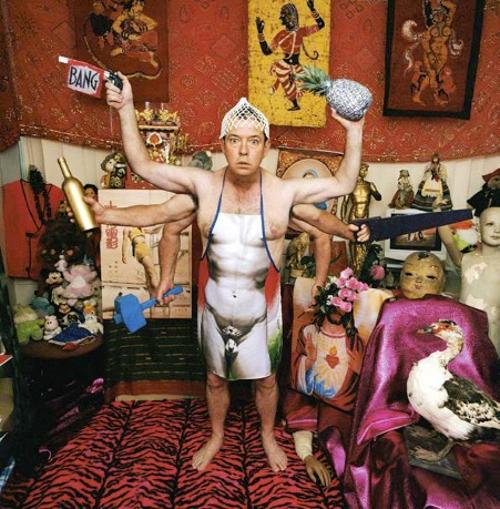

This is mostly a positive thing, but I struggled initially with the choice of Metro Arts for this particular exhibition. Topsy, a show evoking altered physical and experiential realities, seemed paradigmatically at odds with a gallery setting. And the strong presence of this gallery at times battled with a show that also felt strongly physical. Topsy centred on the theme of circus or carnival, that sensual, otherworldly, 'new order of things', to quote Mikhail Bakhtin in the exhibition's catalogue essay. Works played with ideas of surrealism, the grotesque and the anarchic. On this last point, Bakhtin, and subsequently Umberto Eco explored liberation and suppression in the medieval carnival, with the former hailing the events as temporary leave from the power of Church and King. In the 1984 book Carnival!, edited by Thomas A. Sebeok, Eco concluded instead that carnivals were 'authorised transgressions', only conceivable in that they reminded patrons of the rules they were transgressing, thus affirming the law.

There was a sense, then, that Topsy needed to escape completely from its environment, to create and inhabit one of its own; curator Chris Comer had even set the scene with music and covered the windows with theatre-style drapes. But escape completely? Would a more immersive environment, a 'new order of things' have been the order of the day? Possibly – though potentially detrimental to the art.

In the end, it was precisely this meditation on not quite belonging to one place – or more particularly to a rational or conceivable place – that made this show so compelling. Works dealt broadly with surrealism or the rupture of 'rationality' and easy readings. Such ideas were expressed by evoking dualities (the strange yet familiar, for example) or images of 'in-between-ness'. In fact, the gallery – or art – might be compared with carnival. Both exist in physical space, and in law (generally speaking) but to different degrees aim towards transgression. As the catalogue emphasises, the carnival or circus '... is a sojourner of the environment, not resident of it. It does not belong anywhere'.

Big Top by Kim Demuth appeared as though 'sojourning', resembling an extra terrestrial. Suspended like a child's night-light, it expanded inside into a nightmarish diorama. Alice Lang's glittered sculptural objects, resting in her photos on human faces, look both out of place yet strangely familiar: innards turned outwards or grotesque objects of desire.

A large installation by David Spooner included his plush Dimetrodons, a species that he has explained were not mammals or reptiles, but somewhere in-between. These are beguiling in that they're all at once humorously grotesque, sweet and odd. They sat in front of a knitted 'map' and fragments of ideas and words that suggested histories and locations. It's a personal and enigmatic symbolism that seems, in the manner of human experience, in a process of flux and resolve.

Grubbanax Swinnasen's installation of fordigraph prints (The photocopier replaced the fordigraph. Swinnasen's installation included an original fordigraph machine and viewers were encouraged to take away signed copies of the reproductions.) recalled the words of both Bakhtin and Eco. A poignant meditation on ideology and power, the series is about the school as carnival. Both are miniature worlds within worlds, and in Swinnasen's prints, punishments (being banished to the corner, writing lines) strike one as sanctioned madness reinforcing ideology. School also births the dichotomy of 'insider' and 'outsider', the marginalisation, for example, that enforcing 'our' National Anthem causes.

Two works had a surreal 'bent', confounding straightforward readings. Ray Cook's mock-theatrical photos challenge because it is difficult to know how to take them. Can we empathise with the young man who stares out of one, boxing gloves raised? He's beautiful, angry, but where is his reality as he stands before a backdrop of stars? He's somewhat tangible, yet quite removed. Finally, Eleanor Avery's sculpture suspended a plastic horse from a crane-like structure, which was weighted down with concrete bricks. A nonsensical play on physical principles, it had a serious undertone linking nature, labour and 'civilisation', not to mention the carnival animals used formerly for human edification. How easily power breeds cruelty and madness!

Coincidentally, a website tells of an elephant – named Topsy! – who allegedly assisted in building Luna Park on Coney Island. Topsy killed three men. Deciding she needed destroying, authorities supposedly sacrificed her to scientists Edison and Westinghouse who used her to prove their differing theories about electrical current. (See www.roadsideamerica.com/pet/topsy.html)

Overall Topsy (the exhibition, not the elephant) was engaging, rich in good work and ideas that expanded far beyond the limitations of a gallery setting.