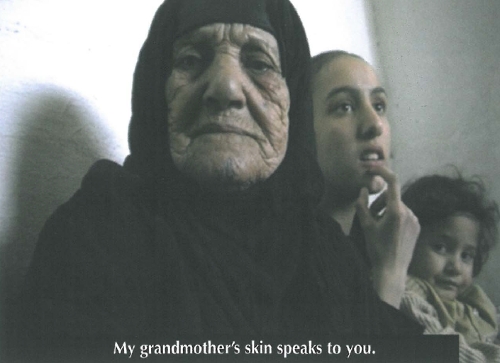

Some ninety years ago, a child was born at Kuntumarrajarra, a waterhole in the south central region of the Great Sandy Desert. On Saturday 4th December 2004, Paji Honeychild Yankarr died having completed over these years one of the most inspiring personal journeys of any Australian.

From birth, she lived with her family around Yirtil a permanent, spring fed waterhole surrounded by her beloved sandhill country. They were living here when her mother announced that her husband had come. She moved, not far, to another stand of desert paperbarks skirting the waterhole, and stayed there, a little frightened with her first companion. He was clearly much older and some time into the relationship, he became ill. She was charged with the responsibility of accompanying him on his departure from the camp and from their world. He died several days after their self-imposed exile and she stayed with his body until she was strong enough to undertake the four-day walk back to Japirnka, the main jila for her family further to the north.

As a young woman she became an accomplished hunter and gatherer of an extremely diverse range of bush fruits, seeds and meat. Mona Chuguna and her husband Peter Skipper remember how well she provided for them in the years in the desert. 'When we were living in the desert, even in weather like today, parrangka we call it, hot weather time, she would go hunting for animals and bush food. All of the kids had to wait in camp. She was a good hunter for us. She collected all of the bush tucker that she put in her paintings. She found wirlka, (sand goanna) and maliri (Hare wallaby) and all of the seeds like kulparn, lungkurn and puturu'.

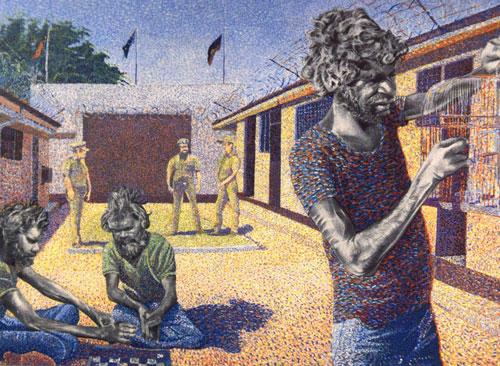

She moved further north to the station country with the last wave of her countrymen in the 1960s. She came first to Timber Creek, a watercourse on the fringe of the pastoral country. She stayed there for several months, afraid, watching the foreigners. Her nephew, the late Jimmy Pike had gone ahead to see the station and he came back for her and several others. They went to Old Cherrabun Station where she worked washing clothes, watering the garden, cutting the grass with scissors and cooking for the stock camp.

In tandem with the introduction of the equal pay laws of the early 1970s, she moved into town, living at the old mission near the newly established town community of Junjuwa. She became involved with Karrayili Adult Education Centre and began painting; as Jukuna relates, Honeychild asked herself what she should do now that her work was finished, 'I will paint my own country, the desert'; and for almost twenty years she did this. Her first images were the product of language classes at Karrayili and these caught the eye of the publishers at Magabala Books in Broome. In 1990 they produced the Boughshed series of cards that included images from fellow artists such as Nyuju Stumpy Brown, Janyka Ivy Nixon (dec), Nada Rawlins and Jukuja Dolly Snell. These provided the impetus for the first Karrayili group show at Tandanya Aboriginal Cultural Institute in 1991. Honeychild was one member of the core group of artists who continued to paint and exhibit consistently throughout the 1990s with shows nationally and internationally.

Her immediate family include some important artists. Jukuna called her jaja or grandmother, she was ngawiji or father's mother for Peter Skipper, aunt to Jimmy Pike, sister for Jimmy Nerrimah, aunt for Wakartu Cory Surprise, ngawaji for Walka Molly Rogers, sister to Llanyi Alec Rogers and Murungkurr Terry Murray called her juku or niece.

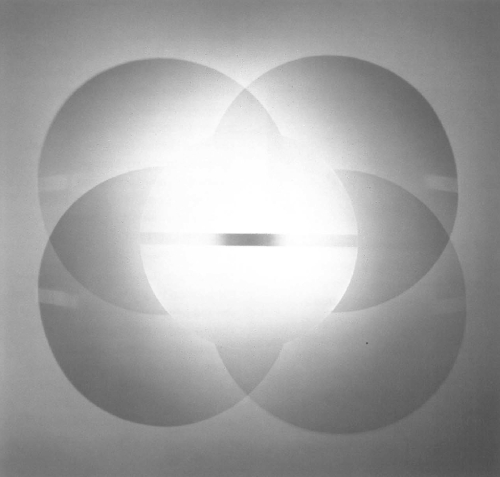

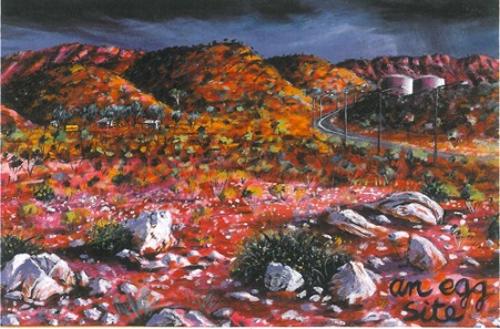

She worked on the two Ngurrara canvases with these and other artists including her late husband Boxer Yankarr. Her works are blatant records of her desert country. The inclusion of bush foods as decorative elements in the work was omitted as she grew older. As she stated in 1994, 'I put water in my paintings, places we were walking around' and this was unchanged as her central motif. To watch her paint, there was a sense that she walked around in her paintings, with the broad sweep of the brush, around the places that she walked as a young woman. The waterholes gradually took over the picture plane with the elliptical forms of the centre of the waterhole, bleeding over the edges, reconstructing precisely the view that she would have known as she drew water from the jila.

For Jukuna, the reason why she should be remembered in these words was for her unswerving efforts to look after her and her siblings as they were growing up in the desert. It was not an easy task but she was a great carer, provider and she knew all of the bush medicines and their applications. She 'grew up' seventeen children although none of them were her own biological offspring. She has many nieces and nephews and is survived by one brother, Watikakarra Stalin.

On Monday 6th December, Mangkaja was closed, in a hopelessly inadequate tribute to a most remarkable individual, hunter, carer and artist.