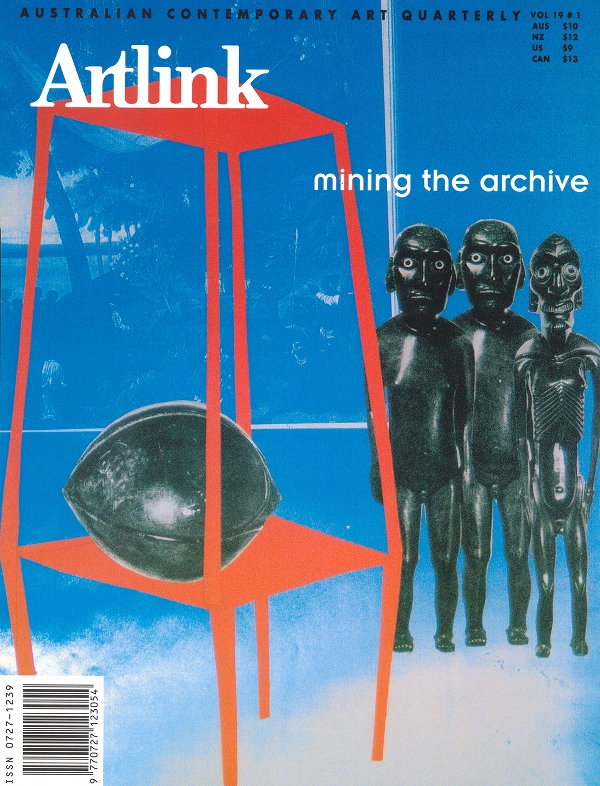

Mining the Archive

Issue 19:1 | March 1999

Guest editor Zara Stanhope. Reflects a range of recent artistic and curatorial responses to particular collections as well as considerations of the nature of archival material and knowledge in the broader sense.

In this issue

"So the question raised for art theory is this....Is a physical autographic sculpture - a Brancusi woodcarving for example - only an 'instantiation'(albeit rather a privileged one) of some imperceptible, intentional object that is the 'real' sculpture? Are sculptures more literally than metaphorically - 'poetry in stone'? Are they in a word 'texts' whose proper reading (as we are told) had best be undertaken in French?"

Four artist's projects initiated by the National Gallery of Victoria engage contemporary art practices and the role of the museum and public galleries as mediators between the collections and the viewers. Impacts on policies regarding the moral rights of artists.

The notion of the artist working with the museum collection is not new. Historically, artists have drawn inspiration from museums and their diverse collections - archaeological, ethnographic, medical, botanical and zoological- as a basis for academic studies and finished works.

Examines two multi-site exhibitions Archives and the Everyday, Canberra Contemporary Art Space September/October 1997 curated by Trevor Smith: and Collected, Photographer's Gallery London June 1997 curated by Neil Cummings. The museological urge in artists has for some time been a part of contemporary practice...leading to the new museology.