An accidental modernist?

Introduction

On a windblown dusty day in late 1992 Kngwarray had returned from Canberra where she received the Keating Award – An Australia Council Creative Fellowship. We sat on her bunk behind her windbreak surrounded by dogs and she entrusted me with a set of photographs produced from the depths of her ubiquitous old ladies' handbag. The much thumbed prints tell the story of these events – the old woman shaking hands with the prime minister surrounded by a forest of cameras; her predilection for hats – on this occasion a bright blue one encrusted with baubles; her close association with countrywoman Gloria Petyarr, and with various politicians, patrons of the arts, and dealers. The most poignant image shows her sitting in a wheelchair, a slight figure in front of an extraordinary painting which dwarfs her by its scale. Although at this point in her painting career she clearly expressed her desire to retire from painting, and regarded the Keating Award as a prize which would augment her pension, she was to continue painting until her death four years later.

For many of us each return to Sandover country is still tinged with the sadness of an absence. I met the old woman first in 1977, when I arrived at Utopia to work with the women, setting up literacy courses and the fledgling art and craft movement.[1] I taught her to write her name, which she continued to do with inimitable aplomb. Ironically this signature – the only thing she could write, and which she originally learnt in order to sign pension cheques with her name rather than with the anonymous cross of the non-literate became a signature of another order.

Acclaimed by some as one of the major abstract painters of the 20th century, the eye of the market has been led by analogies drawn between Kngwarray's work and that of past masters such as Matisse, Monet, Renoir, Kandinsky and De Kooning.[2] In 1990 she had her first solo shows in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. These were followed by many exhibitions both in Australia and abroad, and by her posthumous representation of Australia in the Venice Biennale in 1997. She worked with immense speed and assurance, and in her brief eight year career as a famous artist her output was prodigious, an estimated 3000 works - an average of one canvas each day.

Kngwarray became perhaps the first Australian indigenous female art heroine, in an industry previously dominated by individual male artists (as opposed to the many women who participated in community arts projects). She was a counterpoint to Albert Namatjira, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Rover Thomas and others. Traditional in her life and outlook, she grew up in her ancestral country at a time that pre-dated significant incursions of European settlers into the region. When she became famous she was already an old lady, who lived in an isolated community, and did not speak enough English for her reality to impinge on the needs of the market.

Painting History

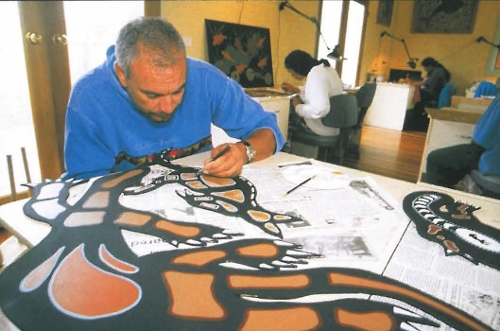

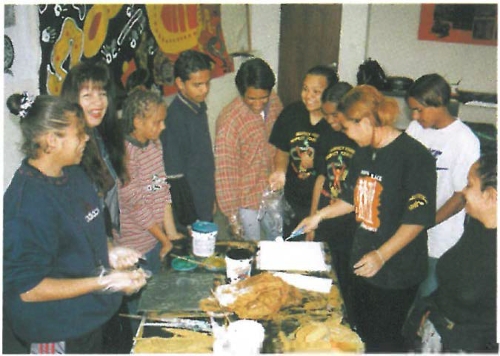

Batik (and tie-dye) was the first major innovation providing the creative link between the traditional and the contemporary for Utopia women, and Kngwarray began experimenting with these newly imported art materials in 1977. For Utopia women, batik was their first experience of using brushes and painting materials, and, like Kngwarray, most had no previous exposure to non-traditional art forms. Kngwarray made no particular distinction between art and craft practice, and spoke of tie-dye and batik as the beginning of her 'other' artistic life.

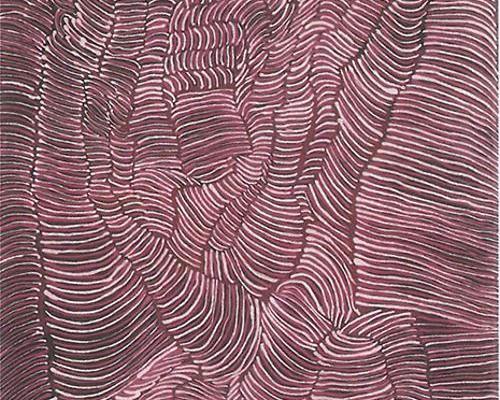

The Utopia women developed a style which is distinctive for its spontaneity – 'the art of free gesture and wandering line'[3] and Kngwarray's early batiks personified this. Frustrated by malfunctioning cantings[4] she worked on, unperturbed by the resulting wax puddles, which she freely incorporated into her designs. This integration of the so-called 'accidental' became the hallmark of the work of some Utopia artists, and of hers in particular.

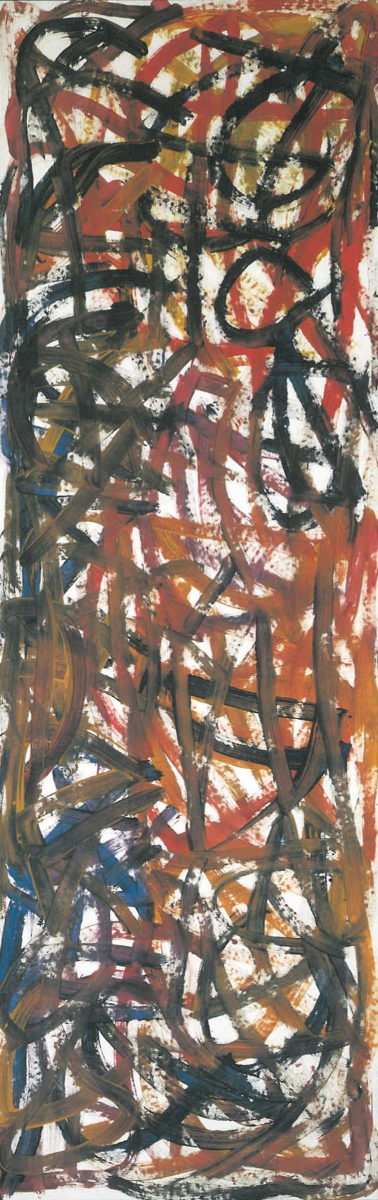

In 1988 Kngwarray changed over from batik to acrylic painting, and in her earlier works on canvas the resonances of batik style are still apparent in the overlaying of colour and images, reminiscent of the layering of wax. For some of the Utopia artists painting was an attractive alternative to batik, being more immediate and involving less technical processing. For Kngwarray the change from batik to acrylic painting was based on pragmatic considerations – she regarded painting as 'easier' and on other occasions gave her failing eyesight as a reason for the change. There is also no doubt also that the economic returns for works on canvas soon outstripped those from batik work.

Symbolism and interpretation

The expectation that Aboriginal art is about 'something' certainly has its origins in early perceptions by a non-indigenous audience that these artworks were best understood in an ethnographic context. Although by no means universal, this perception is based on the fact that marketable indigenous art in many regions of Australia has grown out of what may be loosely termed 'traditional' art forms. Many Aboriginal artists are themselves well aware of the market-enhancing aspect of a 'story', and the value of telling the 'story' is reinforced over and over again in the market place. The willingness of Aboriginal artists to share aspects of their 'story' can also be understood as a generous attempt to communicate important aspects of Aboriginal culture to the wider community.

For artists from Utopia the choice of imagery for use in marketable art forms such as batik or acrylic painting is by no means random – artists paint designs associated with particular country, and this reflects the very precise knowledge they have of their environment and their cultural Law. Although the nuances of difference between various species of plants and animals may seem inconsequential to the outside observer, they are of paramount significance to the custodians of these Dreamings. While the restraints on subject matter operate in the community at an ideological level, this does not preclude experimentation, and the divergence of styles characteristic of these artists is evidence of their creative licence.

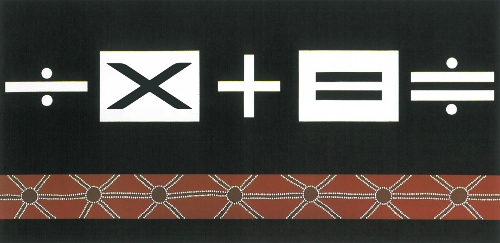

Kngwarray went further than others. Her work challenges pre-existing notions of the 'traditional' in Aboriginal art precisely because she did not use the more familiar imagery of the Western Desert painters – motifs such as concentric circles, animal tracks and stylised implements, which allow the viewer a partial literal reading of the work.[5] As her painting life evolved, her style changed to obscure the residual iconicity in her work. For outsiders the 'story' that linked the artwork to cultural interpretations was not immediately apparent, and, in an art world hungry for explanation, the effect of her perceived reticence to explain has led to much speculation about the meaning of her art, as well as mystification of her persona.

The fact that she spoke almost no English, and that her interlocutors spoke even less of her Anmatyerr language added to the mystique, and the few phrases she is credited with uttering have become almost sacrosanct. Some have interpreted the monumental white lines on black in her yam paintings of 1995 as statements of reconciliation between black and white Australia,[6] and others have read a cosmic world view into the limited documented statements of her intent as an artist. The often quoted 'whole lot' statement – said in response to questions about her painting, but also in response to a question about what colours to order from a Matisse colour chart is a prime example of this mystification.[7] Yet she did have a point of view.

According to Kngwarray's own testimonies, the themes of country and Dreamings in her work remained a constant throughout the transformations of her style.[8] For Kngwarray the locus of this power lay in Alhalker country, her country of spiritual origin for which she maintained a connection inherited through her fathers and their fathers before them. Painting her country was a exercise of right – to nurture, celebrate and protect – and on one occasion, after returning from an exhibition of her paintings in Western Australia in 1990, she said that she had gone there to secure her country from threats of mining.[9]

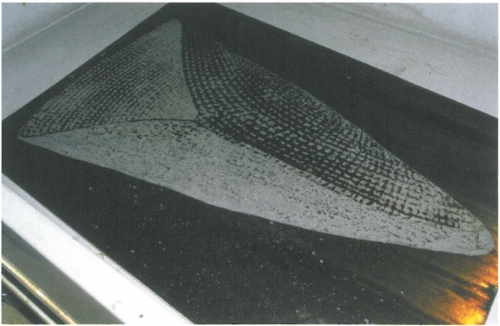

Her main traditional concern was with the atnwelarr (pencil yam), a creeper with bright green leaves, yellow flowers, and edible roots.[10] Over and over in her imagination she recreated the underground network of roots and tubers of the pencil yam – visible as an underlying tracery in earlier works, almost entirely obscured by dots in others, and emerging in bare linear form in her later works. Her name itself, kam, comes from the seeds and flowers of the pencil yam plant, and the practice of naming a person after a particular feature of a Dreaming from where they originated emphasises their personal connection to the Creation.

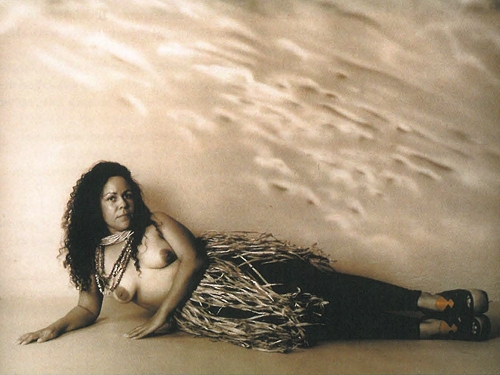

The awely, or women's ceremonies, from Alhalker country were an underlying theme in Kngwarray's work. In the 1970s the visual symbolism of these ceremonies found a new form in the batik designs on silk, and in acrylic paint on canvas. In 1994 the profuse dotting which had characterised Kngwarray's earlier work was replaced by more austere works of bold, often monochromatic, linear gesture. This imagery has been interpreted as signifying the markings, called arlkeny, which are the basis of the body painting for women's awely ceremonies.

Individual fame or collective anonymity

My own position in relation to the 'Emily phenomenon' remains equivocal. In the early days of the batik movement at Utopia she was an indomitable and energetic force, producing work of astounding and idiosyncratic beauty. She was an accomplished hunter, a great singer, and she had a perplexing sense of humour, the nuances of which I would never claim to fully understand. When she became a painting heroine my personal feelings ranged from appreciation of the finest work–which has that indescribable quality which moves the spirit–to anxiety about the social price she was paying for fame.

A biographer of Jackson Pollock said of the New York school that 'the media needed one person – they couldn't go to the public with a community'. This comment could also have described the tension that exists in Aboriginal communities between the place of the individual artist as a star of the art market, and their position within the context of their kinfolk and on-going obligations within the community of artists.[11] Kngwarray's trajectory to fame in the later years of her life embodied these contradictions – she became famous – others did not. As her success escalated, others from her country group were puzzled by the disparity between the financial return they received for painting, and the prices Kngwarray commanded – after all it was the same country, the same story. Furthermore, Kngwarray worked faster, and with seemingly less care than her countrymen and women – she was never an exponent of the minute and careful dotting techniques, and used large brushes and bits of old thong to apply the paint, rather than satay sticks. As her career progressed her technique became wilder and freer.

I also found myself at times looking backwards over my shoulder, preferring the earlier works and not immediately appreciating the new. Whether this was based on nostalgia, or on my own innate lack of sophistication, at any rate she broadened my view – she grew me up. In a wider sense the radical departures of her style provided a conduit which signalled a new phase in the appreciation of the work of Aboriginal artists, less reliant on interpretation guided by the paraphernalia of ethnography or 'eurocentric' art theory.[12] A more detailed story may one day emerge from the community to which she really belonged, and who no doubt understand the complexity of her story better than anyone.

Footnotes

- ^ For discussion of the beginnings of the batik movement at Utopia see essays by Green and Murray in Ryan and Healy (1998) 2 See Jane Cadzow Good Weekend 1995 . Terry Smith in Isaacs (1998:24-42). Margo Neale (1998:23).

- ^ See Jane Cadzow Good Weekend 1995 . Terry Smith in Isaacs (1998:24-42). Margo Neale (1998:23).

- ^ Ryan, J & Healy, R (eds) (1998) Raiki Wara. Long Cloth from Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait. National Gallery of Victoria.

- ^ A canting is a small Indonesian tool shaped like a pipe that is used to direct fine lines of molten wax onto fabric in the process of batik making

- ^ See Roger Benjamin (1998:47) in Neale

- ^ Daniel Thomas (1998) says that "We cannot help but read these austerely graceful canvases as grand statements of black/white racial equivalence.' See also Terry Smith in Isaacs (1998:41), Roger Benjamin in Neale (1 998:48), and Time Magazine July 1 6, 1990

- ^ An information panel at the Queensland Art Gallery in 1998 stated: 'Later, she declared that her work encompassed "the whole lot", suggesting that Kngwarreye was well aware that her a:rt dealt with transcendent realities. "Whole lot" is another way of saying that her paintings express wholeness, a seamless totality." See also Janet Holt (1998)

- ^ These comments are based on conversations I had with Kngwarray in her language, Anmatyerr, over a period of many years.

- ^ Although title to Utopia Station was handed over to the traditional owners in 1981, as the culmination of the Land Claim process, Alhalker country was not included in this claim as it lies substantially to the west of the claim area on a neighbouring pastoral property.

- ^ Although non-Indigenous scientists only recognise one species of this yam (Vigna lanceolata), Aboriginal people name two distinct plants - atnwelarr and arlatyey. Kngwarray also painted other Dreamings including ankerr (emu - Dromaius novaehollandiae), intekw (fan flower - Scaevola parvifolia), akatyerr (Solanum centrale), and ywerrk (wild fig - Ficus platypoda).

- ^ See Terry Smith (1998:26) for comments on the role of self expression in contemporary Aboriginal Art

- ^ See Roger Benjaminin Neale (1998:53)