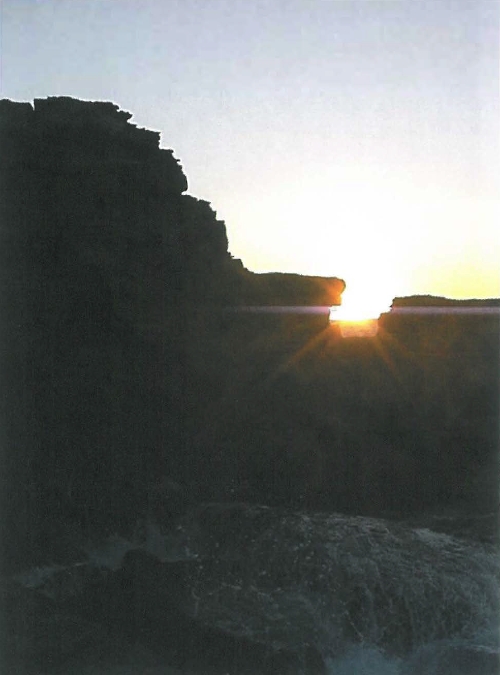

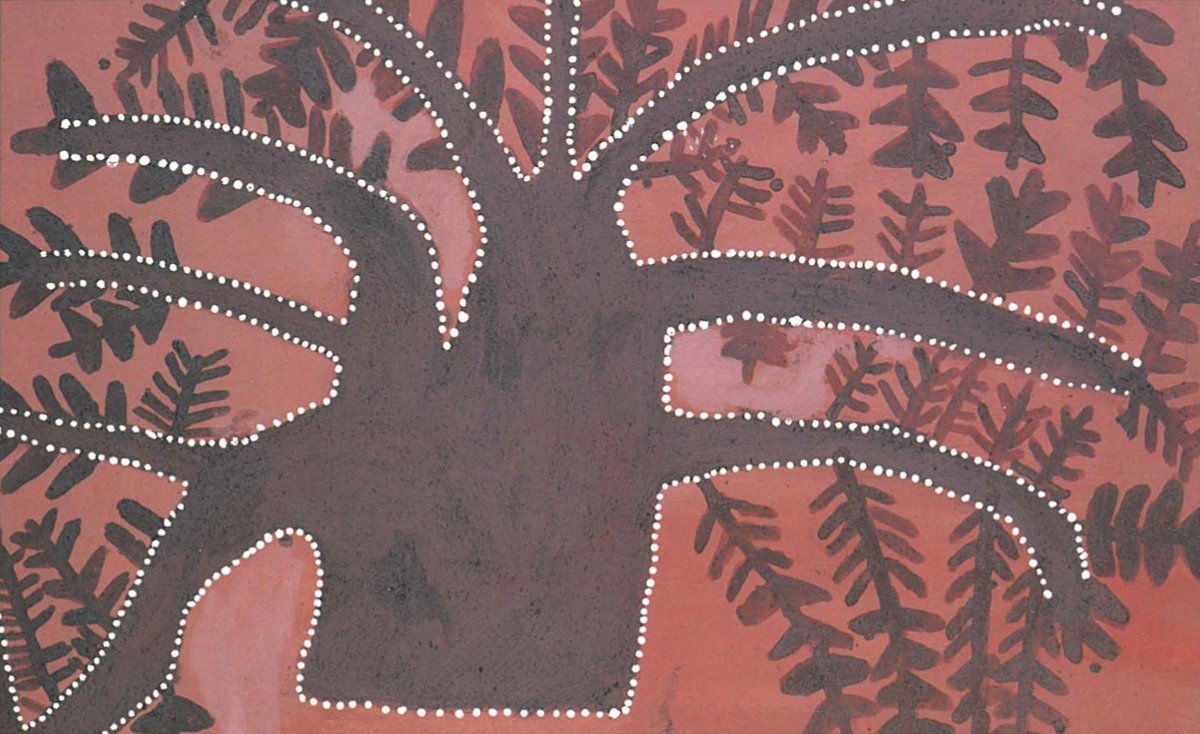

"Yarlka, this white mountain, this my spirit place. My mother, old Dinah, she found white porcupine la swag la Yarlka. That porcupine [echidna] was me. That white stone from that hill, they break him up for spear. Good spear, that one." (Queenie McKenzie, tape 1994).

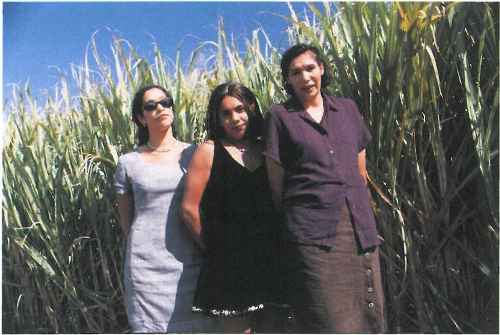

Queenie McKenzie (formerly Oakes), or Mingmarriya, was born on old Texas Downs on the Ord River in the rugged East Kimberley. Indeed, she lived there all her life until the respected manager, with whom a close knit group of Aboriginal people ran the cattle station for many years, retired. The 'Texas Downs mob' then all moved to the Warmun Community at Turkey Creek, which was located on an adjacent property. Queenie was therefore focused on a locality from which she never moved, a landscape that she knew intimately: 'Every rock, every hill, every water, I know that place backwards and forwards, up and down, inside out. It's my country and I got names for every place.' It was this singularly close relationship with her country, that prompted Queenie to take up painting, but not until she had already led a full and energetic life.

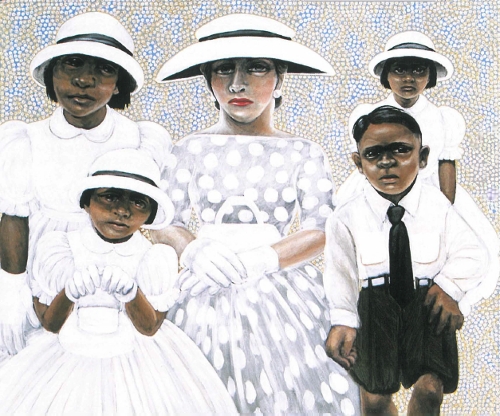

Queenie's mother Old Dinah, a Malngin woman, was a stalwart supporter of 'women's law business' which Queenie came to inherit. Her biological father was a white horse breaker who returned to Queensland, while the 'real' father who took responsibility for her was a Kija song man with strong links to the ancestral spirits. Despite her light skin colour and fair hair (her nickname was Garagarag, meaning 'Blondie'), Queenie was miraculously never taken from her family to be institutionalised as part of the official Government policy of assimilation. With no mission contact and no western schooling, her background was therefore truly that of a traditional station Aboriginal, which included a practical knowledge of managing cattle and riding horses.

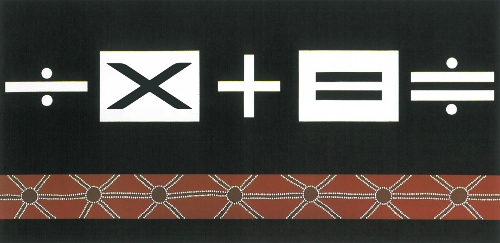

Old Dinah and her daughter eventually became stalwart supporters of Roman Catholicism when a member of the Texas Downs mob returned to the station after prolonged treatment in the care of Catholic sisters at the Derby Leprosarium and became a dedicated proselytizer. Queenie's hearty singing will long be remembered at the Warmun services where a particularly Aboriginal flavour was introduced to the sacrament sung in the Kija language. There were no apparent conflicts in Queenie's mind between her traditional and her Christian beliefs.

Queenie and her husband Charlie McKenzie had no children of their own, but adopted a son Jason who grew up to give her several grandchildren, many of whom she also brought up. Queenie enjoyed close companionship (though she was also quick to berate misbehaviour and to retain her personal space), and in her later years as a widow in the pensioner's quarters at Warmun, she always shared her large bed with a dog or a grandchild or both.

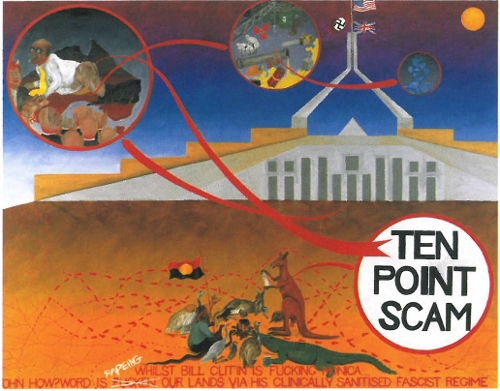

In community affairs, Queenie's forthright and decisive personality was a power to be reckoned with, and she threw her considerable energy into assisting with health problems in the clinic, working out methods to cope with the invasive alcohol problem, teaching the Kija language and culture in the school, and empowering the women through encouraging them to participate in 'women's law business'. Indeed, Queenie's first ever drawing, made in 1982, was to reproduce the body painting and associated gear used in the women's ceremony of which she became the keeper.[1] Later, in the school classrooms, she soon realised the power of pictures as a teaching aid. Initially, she lacked confidence to do the illustrations herself and asked a younger, educated woman to help. Slowly, she experimented with representational art herself and her earliest paintings, done circa 1986, show dreamtime stories about Emu and Crow, and of Mary the Mother of Jesus.[2]

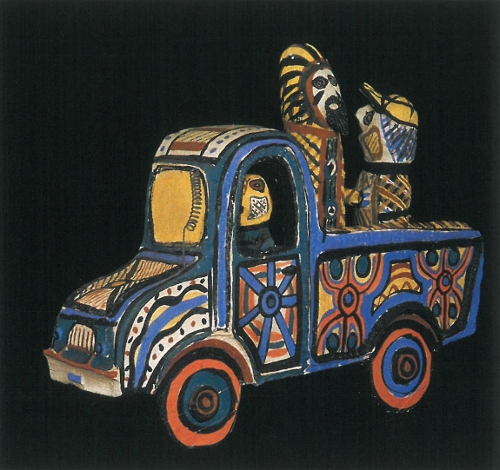

During the late 1970s, when Queenie was actively involved in defending a women's site that had been damaged as a result of diamond mining, Rover Thomas (one of the Texas Mob), introduced a new dance. The performance was dramatised by painted boards of country held on the shoulders of the dancers, but only men were involved in the painting. Later, Paddy Jaminji and Rover Thomas became well known for their art which derived from the dancing boards, and the paintings fetched good prices.[3] Later, in 1990, while Queenie was camped in the bed of the Ord River at the foot of her beloved Wertim (Red Butte Mountain), she made a side elevation drawing of the mountain in the sand, and declared that she too, could make paintings like Rover Thomas. And that was the start of Queenie's career as a painter for the commercial market.

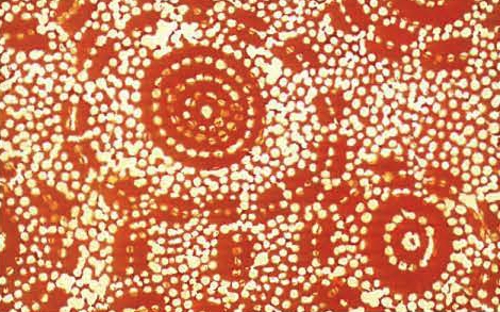

By this time, Queenie, now a widow, was living in the pensioner's quarters at the Warmun Community where she was fed and cared for without the responsibilities of running her own home. She had time and she had energy, which, from then on, she directed towards painting. Canvases were provided by the community co-ordinator or by Aboriginal art organisations or, in some instances, by private individuals who requested paintings. The natural earth pigments came mostly from the hills around Turkey Creek, but as Queenie became too old to dig the ochre herself, she traded with others who were fit or bought a supply through Waringarri Aboriginal Arts in Kununurra. When she discovered the technique of mixing the pigments to create different colours, she particularly liked the pink effects obtained by mixing red ochre with white kaolin, and shades of pink became a hallmark of her later works. Unlike Rover Thomas's plan view paintings, Queenie's landscapes were mostly represented in profile, but with features such as rivers and roads inserted in plan. As Queenie's work became better known and was represented in most of Australia's major art galleries, she was encouraged to identify her work with a finger print, but she soon learned how to write her own name. However, for all other purposes, she remained non- literate to the end of her days.

Queenie displayed no hesitancy when faced with a blank canvas, and her painting style was therefore characteristically decisive and vigorous. At times she almost scrubbed the paint on the canvas, and if she did not like a particular shape or colour, she would summarily paint over the top of that section. She often found finishing off her work tedious, and one sometimes thought the matchstick with which she applied the outline dots would go right through the canvas. While she was painting, she showed no particular reverence for her work, often placing cups of tea or plates of food on the canvas, or propping her work casually against a wall among her beloved dogs.

Invitations to participate in exhibitions or workshops all over Australia broke the tedium of her work routine and, as her paintings commanded higher prices, Queenie opened a savings account. She was very proud of the sum that accumulated, but was also generous to a fault in the amounts of money she was forever distributing to her adopted family. Once she had material security, Queenie stopped gambling, and was also very proud of the headstones, paid for by herself, that were erected in the Warmun cemetery in memory of her mother, her brother and her husband.

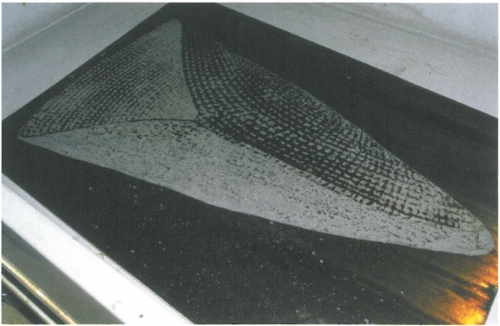

During the year before she died, Queenie was honoured by being chosen, with eight other Australian artists, to create prints to commemorate the Olympic Games in Sydney, and she was also among eleven Western Australian artists selected by the State Government as 'Living Treasures.' Over the last 14 years of her life, Queenie was an almost obsessive painter, producing canvas after canvas with frenetic energy. Some of her subjects addressed social topics such as drunkenness and massacres, but predominantly, her work was simply her country and the lore that the landscapes embraced. She not only touched the lives of many people in different walks of life, but also influenced them and left her mark.

In later years, when Queenie could no longer get about easily, she turned to painting her country with as much energy as she used to walk and ride. She revisited all the familiar places in her mind, then painted her visions on canvas to share with the world. Her deepest wish was that Texas Downs should be turned over to the Texas Mob to run as a cattle station, but she died suddenly, in November 1998, before the realization of this dream.

Footnotes

- ^ Vinnicombe, Patricia Women's sites, paintings and places: Warrmarn Community, Turkey Creek. Report on a project with Queenie McKenzie, funded by the National Estate Grants Programme

- ^ ibid p44, and photographs taken by Sister Veronica Ryan in 1990, Library of the AIATSIS, Canberra

- ^ Roads Cross: the Paintings of Rover Thomas, National Gallery of Australia, 1994