Eco-Critical

Issue 44:1 | Parnati–Kudlila / Autumn–Winter 2024

Eco-Critical lands as the ‘hottest year ever’ is declared (again), and scientists formally reject the Anthropocene as an epoch in geologic time. How do we précis such apparent incongruities? This issue rallies writers from across our region in response to the climate crisis and how it manifests in exhibitions, works of art and creative activism. As a collection of ecocriticism, Eco-Critical offers a survey of the ways artists and writers are using the raw materials of image and language to engage with these momentous issues now—whatever the terms.

In this issue

Tough luck to the wood that becomes a violin.

– Arthur Rimbaud, letter to Paul Demeny, 15 May 1871

The picture which is looked to for an interpretation of nature is invaluable, but the picture which is taken as a substitute for nature, had better be burned…

– John Ruskin, Modern Painters, 1844

Like an enveloping atmosphere, ecology has become a dominant framework for contemporary art. In parallel, criticism has assumed the task of interpreting and re-interpreting art and its history for the ecological moment. Despite its near-imperialistic tendency to redefine the meaning of art works in ecological terms, the use of ‘ecology’ as a framework often precludes critical analysis rather than invites it. We are compelled to equate ‘ecological’ alongside terms like ‘life’ and ‘care’, with ‘good’, neatly bypassing both aesthetic and political judgment. Ecology is levelled to any lively, activated network, ignoring the dead, inorganic and artificial aspects of real ecologies. In the efflorescence of eco-art, the living overtakes the dead at the cost of art’s function...

To continue reading...

Lucienne Rickard’s Extinction Studies (2019–2023) was a long durational, live drawing project commissioned by Detached Cultural Organisation and staged in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s Link Foyer spanning four years and three months. Delivered in two iterations, the project focused on extinction as a key concern of the global ecological crisis and a phenomenon much talked about, but rarely witnessed at close range. Informed by links between the destructive impact of human activity within the Anthropocene and the ‘sixth’ mass extinction event, Rickard’s daily presence in the Museum framed extinction as a phenomenon to which we might bear witness in the here-and-now. Employing the double-edged strategy of drawing an extinct or endangered animal on a large sheet of paper and then erasing the image, Rickard’s project alluded to evolutionary cycles as viewers could witness, sometimes over months, the emergence of an anatomically accurate creature, only to watch it disappear in minutes under her eraser.

To continue reading...

It’s 2am, and I am editing images on my MacBook Pro to include in this visual essay. I am using the Pomodoro method while I work, my iPhone keeping track of time. I am thinking about rare earth elements (or REEs, or rare earths) and their wide use in contemporary art, particularly media art, photography, video, film and animation. If life cannot be separated from art, then it is impossible to have an art practice in 2024 that does not depend on the mass-scale extraction of stolen Indigenous land and resources.

To continue reading...

2022 Tiyari, Tiwi season of hot and humid. We felt unsettled watching the news of Jikilaruwu Tiwi Island clan seniors taking South Korean Government to Seoul Central District court; a sip of solidarity beyond state borders to halt financing Santos and SK E&S Barossa Gas Project near Tiwi Islands. But the court dismissed the case after two months as foreign environmental rights are inaccessible to the Korean constitution. In scrutiny, ‘rights to clean air’ as basic rights is categorised under South Korean private law, which was a seeded sacrifice when the constitution was first drafted in the ‘60s after the Korean war—the beginning of economic boom and resource privatisation. This underlying legislative code of proprietary extractions has been reinventing “natural environment”, “resources” and “wealth” using becoming-Global-North colonial science, where the environmental law in Northern Australia is sprouted from these legislated Ponzi schemes.

To continue reading...

I have never seen a Gouldian finch “in the wild”, but over the past two years I have become familiar with its image on signage in Darwin streets and byways along with the words Save Lee Point. This typically shy, mostly silent and endangered bird is the brilliant icon of a grassroots movement to protect one of Darwin’s last remaining woodland corridors.

To continue reading...

Some things won’t change, a woman told me in a small room on Bundjalung Country, filled with other women weaving; the smell of raffia and pillows. It was raining so we couldn’t sit outside. I began to weave a circle.

We thought we trusted the bush to be there, but then fire comes, Ruth said. We thought we could turn to the river, but then it overflows. The places we take refuge don’t feel so safe. But we can count on galaxies and bacteria and stones to be around long after we are gone.

Driving my carbon-belching hatchback from one colonial settlement to another, I listened to a book about microbes under a slivered moon. Fires flanked me at one point on the road. They weren’t close enough to scare, contained, but there: the contents of my gut, and the flames.

To continue reading…

The art-raft project is, in Hakim Bey / Peter Lamborn Wilson’s words, a materialised ‘temporary autonomous zone’, where collaborators and activists have space to playfully propose questions, be involved in a common cause, generate connection and envision more positive future narratives.

The project began as a response to the needs of the People’s Blockade, a peaceful ‘flotilla’ protest organised by Rising Tide, held annually in the harbour and river mouth of the Coquun/ Hunter River, at Muloobinba/Newcastle. United on Awabakal and Worimi land and waters, the November 2023 protest saw 3,000 people occupying the world’s largest coal port for 34 hours.

To continue reading…

South Australian creative duo Laura Wills and Will Cheesman are the artists we need for the future. Partners in life and work, the pair have collaborated informally for nearly two decades, since the mid-2000s. Working across public art, relational and participatory practices, the duo—formalised as Wills Projects in 2020—invite many hands to co-create and deliver their projects, promoting non‑hierarchical structures of engagement that cater to the capacity and diversity of their participants. Based in Tarntanya / Adelaide, on Kaurna Yarta, Wills Projects is an exploration of the artists’ action-oriented yet reflective way of responding to the world. Prior to meeting, the pair lived parallel lives, riding bikes around Australia, living in squats in Europe, volunteering and WWOOFing, all while creating art. These experiences brought them together in what Wills refers to as ‘a shared culture’.

To continue reading...

decolonial poetics (avant gubba) (2017), by Bundjalung poet Evelyn Araluen, captures a poignant facet of Katie West’s practice: ‘there are no metaphors here’ [poet’s spacing]. Amid the turbulent aestheticisation of changing climates, biodiversity, colonial legacies and land management, Araluen cautions us to ‘…not touch the de’ [poet’s emphasis]. The rapid adoption of “eco-critical” and “post”-colonial curation, making, staging and writing, in recent times, manifests in work that leaves us with an ecological feeling, a subtle gesture or zephyr. The process of decolonisation, however, cannot simply linger in the air, resting in the conceptual world. Nor can the “eco‑critical”. There is little room for the metaphorical rendering of these material challenges. The relationship between anticolonial projects and environmental consciousness is pervasive, and the health of Country mirrors the health of peoples. The theft and degradation of land always follows in colonialism’s footsteps: Violence inscribed upon the land is inscribed in both minds and bodies.

To continue reading...

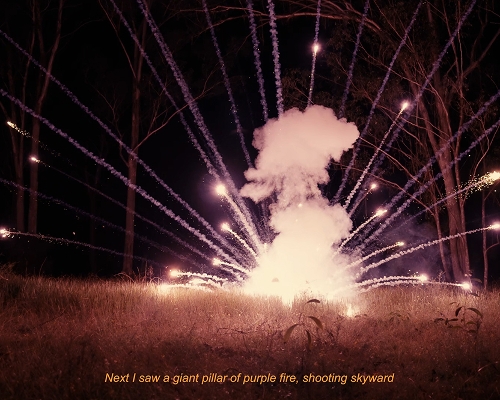

In addition to the well-known effects of climate change—melting ice caps and rising sea levels, the increasing frequency of natural disasters, drought and dangerous heat—there are more subtle, psychological affects: feelings of anxiety or dread while thinking about the future, exhaustion and fatigue when reading news stories about the climate emergency, or a churning stomach when trying to come to terms with our limited agency in the face of this capitalism-induced climate crisis.

To continue reading...

Leading up to the first sculpture exhibition held in the grounds of Hans Heysen’s 132-acre property, The Cedars, in March 2000, the area around the shady pool, the site of one of Heysen’s iconic paintings, had slowly been cleared of the head-high broom that covered much of the estate. The back-breaking working of cutting and swabbing the weeds was undertaken by a group of volunteers headed by environmentalists Trevor Curnow and his partner Helen Lyons as the group Trees Please! (an offshoot of Trees for Life), established in 1998 to support the preservation and regeneration of the remnant bush at The Cedars. The late Helen Lyons was a local Hahndorf artist, and her connection with The Cedars landscape inspired her idea of holding an exhibition of installation-based artworks in the vicinity of the shady pool. She had previously founded The Artist’s Voice collective in 1997 and had artists ready and willing to be involved in the venture. The Artist’s Voice members exhibited regularly at the Hahndorf Academy’s upstairs gallery, but some members were open to Lyons’ vision for a non-commercial, experimental exhibition at The Cedars focused on environmental principles. The Cedars’ long-term curator, Allan Campbell was also supportive, and Lyons invited the twelve participating artists to make works in direct response to the landscape, making use of materials found on the property. This inaugural exhibition, A Homage to Nature was the first of many, now known collectively as the Heysen Sculpture Biennial, a series which can be considered a visceral response to the environmental art movement that emerged globally in the 1960s.

To continue reading...

Related issues