Layered with visual and conceptual ambiguity, Yuki Kihara’s photographs, video and texts point to (or jab at) the limitations associated with illogical binary views of people, cultures and the world. Disturbing the Eurocentric notion of the canon, Kihara’s installation Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King for the New Zealand Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale, is an interruption that collapses boundaries between contemporary art, art history and Pacific geography. Kihara offers photography as a means of unpacking the complexities of colonial representation, visibility and ethnography of global cultures as they exist in Paul Gauguin’s late nineteenth century Tahitian paintings.

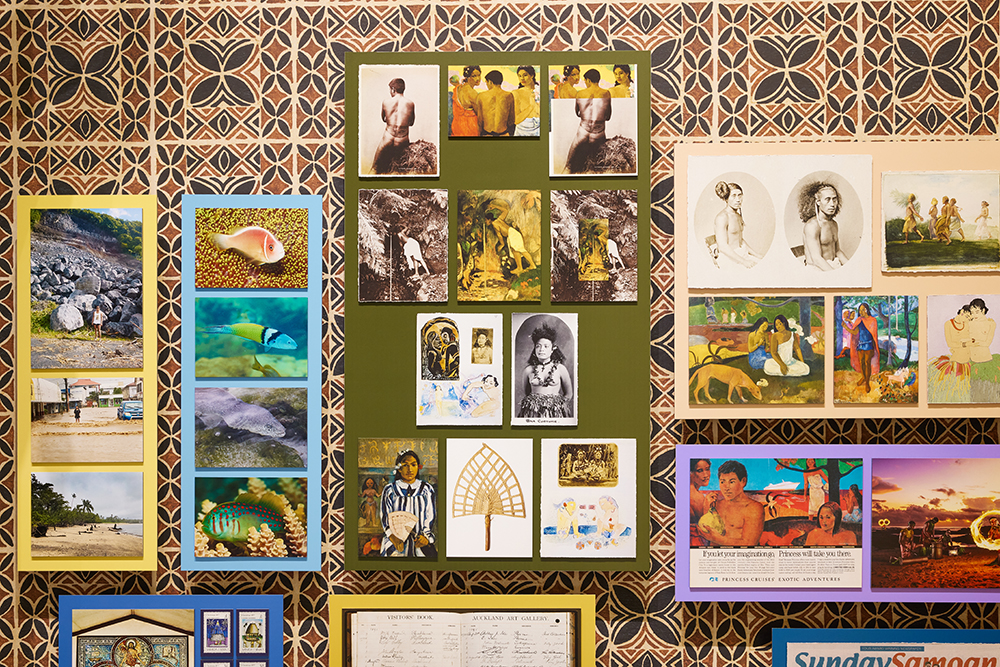

The main body of Kihara’s photographs, unadorned with frames or glazing, are mounted in a cluster on a digital wallpaper image of an idyllic Samoan coastline. This installation pays considerable attention to the subjects of the images while maintaining the travel brochure-like idealism of island, ocean and tropical climate. Other works are mounted against wallpaper printed with siapo or tapa design, the painted bark cloth made in the Pacific Ocean Islands, particularly Fiji, Samoa and Tonga. Set against the geometry of traditional patterning, these images appear contextualised within a bigger narrative of continuity. The idea of being ‘schooled’, as is suggested by the tableaux nature of the display, quickly dissipates as the viewer engages with the images and discovers the sense of fun that arises less from a singular voice (Kihara), and more from the thoughtful and riotous collective of Samoan fa’afafine, who recognise third and fourth genders.

Nuanced and multi-faceted, the title of the project Paradise Camp reveals Kihara’s capacity to simultaneously appreciate, laugh at and critique Gauguin’s work involving Pacific Islander cultures. ‘Camp’ for example is likely derived from the French term se camper, meaning ‘to pose in an exaggerated fashion’. Suggesting kitsch, wit and flamboyance, it’s use in the title shifts the emphasises towards the subjects of the paintings, rather than the artist’s fetishising of them. Also referring to an outpost and a collective of supporters of a particular party or doctrine, ‘camp’ implies both tightly focussed and expansive. ‘Paradise’, another loaded (and gendered) term, is suggestive of the Old Testament’s Garden of Eden in which ‘woman’ succumbs to temptation, and introduces humanity to concepts of shame and evil. ‘Paradise’ conjures a carefree world, untouched by the trappings of materialism.

Popular culture offers the most direct (and rewarding) access to the wealth of Kihara’s ideas. Filmed, acted and scripted as subversive mimicry of morning—or more accurately mid-morning—free to air TV), the videos are manifested as a whacky tacky talk show mashup that is part documentary, part mockumentary and part game show. First impressions: Paul Gauguin is a five-part series which captures candid responses of a panel of the Samoa’s fa’afafine community to Gauguin’s iconic paintings.[1]The panellists view the post-impressionist paintings through the lens of their own lived experiences in Samoa, and speak generously and openly about gender inequality, Christian shame, nakedness, the body and hormone treatment. Their discussion of Gauguin’s work in First Impressions: Paul Gauguin is frivolous, bitchy and heartfelt… words that can also be used to describe the highly subjective, competitive and unregulated world of contemporary art.

In one such work, Kihara, via a prosthetic transformation, presents herself as Gauguin in an attempt to ‘understand’ him. Speaking artist to artist, she proceeds to interview her ‘Gauguin-self’, calling out his (in)appropriations of Tahitian culture and his subsequent denial of the appropriations in his journal first published in 1901 as Noa Noa. Kihara’s dialogue with her Gauguin alter ego demonstrates her brilliance at using humour and satire to highlight the impacts of colonial male arrogance. Kihara presents Gauguin with clear evidence of his direct appropriations of Samoan culture, and he has nowhere to hide. It quickly becomes evident that Gauguin never imagined a world with Google images, nor did he ever anticipate a world in which anyone might question his methods and attitudes. Kihara the artist has the last word in this dialogue, ensuring that her Gauguin self is aware of her importance by telling him that shemust leave the interview because she is exhibiting in the Venice Biennale.

Kihara’s use of photography to de-centre and re-centre who is looking at whom cannot be underestimated in her investigation of Gauguin. More specifically, her still photography and video evidence a kind of symmetry at play in her analysis. As Kihara hilariously points out, Gauguin used ethnographic photographic material of Samoans as a source for his paintings. Gauguin could never have imagined that over 100 years later, Kihara would use his paintings as ethnographic source material for her photographs. Gauguin uses a rich but muted palette to imbue his work with a dreamy haunting psychology. His paintings, while tonally complex, are not bursting with joy. Instead, his figures seem charged with a mysterious internalised emotion. In contrast, the colour in Kihara’s photographs is gloriously lush and vivid. Her images can be understood as sophisticated, larger than life transpositions of Gauguin’s compositions that highlight his consumption and abuse of paradise. Gauguin used photography to create paintings for western audiences. Kihara has used Gauguin’s paintings to create video and photographs for Samoan audiences. Kihara describes her process of inserting members of the fa’afafine community into the roles in Gauguin’s works, as ‘upcycling Gauguin’. Distinct from recycling, upcycling refers to the reuse of discarded objects or materials to create something of higher quality or value than the original—in the case of Paradise Camp, a suite of images that restore, generate and engender visibility.

The notion of interruption seems central to Paradise Camp. Kihara’s work is an interruption to Gauguin’s binary view of the world as either primitive or civilised. The videos and photographs throw shade on Gauguin and the cultural arrogance associated with his art: the ‘primitivist’ appeal for which it was once celebrated is now its greatest flaw. A further demonstration of interruption to conventions of art critique is that Kihara’s process grants agency and authority to people who have mostly been excluded from this role, yet have lived experience to draw from and to inform their authority. This aspect of Kihara’s work points squarely at the problems and limitations implicit in colonial legacies in contemporary art, art history, museology and curatorship; by giving overt presence to fa’afafine, Kihara interrupts standard narratives of the ‘native’ and portrayals of gender. Potently articulating the idea that in art, one can never be certain of what they are looking at, Kihara’s imagery dissolves the assumption that viewers are looking at women or girls in Gauguin’s paintings. The real joy in these works is that there is no compulsion to pass the fa’afafine as something else, nor is there any attempt to fly them under the radar. Importantly, the images suggest the acceptance and celebration of third and fourth genders in Samoan culture.

Kihara’s work injects a welcome and all too rare sense of humour into the often-impenetrable seriousness associated with art history’s notions of ‘heroic genius’ tropes. It’s the clever messing with one of the bastions of Western art that lies at the heart of Paradise Camp, which transcends the one-line gag of a prankster. The works evidence a profound respect and desire for deep looking, expansive reflection and focussed interrogation. Although there is a cultural specificity about Kihara’s imagery, its resonances are universal and urgent. Paradise Camp calls into question the relatively unquestioned canons of Western art—not just the artists and the art, but more importantly the seeming immovable structures held in place by fat books, museums and other forms of authority.

Paradise Camp will show at The Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, 24 march – 31 December 2023.

Footnotes

- ^ First Impressions: Paul Gauguin, 2018 is a 5-part episodic talk show presented on Samoan television and co-commissioned by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Denmark

2018_watercolour and gouach on tracing paper.jpg)

- Fotografer Ariyanto Nugroho_card.jpg)