Entering the Samstag Museum I find myself amid a cacophony of things both material and abstract, including histories, objects, relationships, people, houses and plants that inhabit liminal cultural zones or sit outside formal archives. Upstairs Madison Bycroft’s film BIOPIC or Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée takes the story of eighteenth century French diplomat Chevaliere d'Éon into wild territory while below, Alex Martinis Roe’s To Become Two (2014–2017) is a carefully observed archive of female relations carrying radical restructuring potential. Both artists, through very different means, have created works that cultivate meaning and power by reimagining histories.

Bycroft’s BIOPIC or Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée is filmed in a grand, disorienting house. Part home, part boat, the architecture is spoken about as being terrestrially attached via barnacles and limpets and the inhabitants bail out its hull against the threat of breaking its fragile moorings. The Estate is in an ongoing process of being mastered by means familiar to colonial Empire-building: taming the land (the Chevaliere proudly proclaims that the marshes have been shaped into an Eden of exotic species); guarding the house (wearing absurd crested armour); mapping ‘uncharted territory’ (all now thoroughly surveyed, we are assured). But most of all, it presents systems of taxonomy that need to be learnt, repeated and ingested (the ritual eating of sea urchins along with nomenclature exercises). The order of things are disturbed however when the Chevaliere, while night gardening, comes across a plant with previously unknown properties, including the will to move of its own accord. This finding challenges the known world, and when emissaries of the (potato head) King make clear that there are no new names nor capacity to extend beyond a ‘rooted condition,’ The House d'Éon enters a state of revolt.

But despite appearances and the labours of the characters, The House d'Éon was never really stable; from the outset it seemed to be on a voyage of errantry, perhaps of the kind Édouard Glissant describes in counterpoint to the rootedness and straight lines of colonialising forces.[1] BIOPIC is full of ambiguities and metamorphoses creating tremors between being one thing and another that destabilise the house. While the Chevaliere is referred to as ‘he’ within the film (born in 1728, living between France and Russia) ‘they’ inhabited the roles of spy, soldier and diplomat, and lived as both man and woman, as the feminised noun infers.[2] In Bycroft’s film this central character is powerfully portrayed by Dolly West and the film touches on, rather than explicates, a life ‘told in misrecognitions, omissions, visibilities and invisibilities’.[3] Bycroft describes this as a queer film, in part because it addresses queer history (its representations and negations) but primarily because the creative process involved queer and trans methodologies of production and collaboration, exploring the potentials of a queer aesthetic, unfolding, unformed and forming.[4]

Held together in The House’s fold are three young characters Lu, Andrea and Charlie, who are at once child/student/protegee/worker, or parts of a sprawling self with names derived from the eponymous Chevaliere Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée. These players are shown in the process of rehearsing, internalising and training towards anchorage in the estate, but are prone to unexpected flights of rebellious desire. The house has hidden parts. Downstairs is a world of soft-sculpture pink intestines and poetry from where illicit texts call out to the inhabitants, allowing them to see their house afresh and with it the possibility of freedom from its enclosure. Andrea describes the budding change within herself as a civil war, ‘If you chase the wild out the door she will come through the window’ she says, of the uprising in her nether regions. There is an echo here of the work of feminist conceptual artist Claire Fontaine (a singular identify, created by a collective of women and named for a notebook), who offers the provocation to begin a ‘human strike’ by starting with refusal of structures already swallowed, to prevent them taking shape within us.[5] Here too, the powers of wildness recall Jack Halberstam’s celebration of the uncivilised (anti-colonial, anti-capitalistic and radically queer) in his book Wild Things (2020) where a call to bewilderment (moving in the opposite direction to colonial knowing, into the woods) disorders the structural inheritances of modernism that we inhabit and that inhabit us.[6]

BIOPIC is an example of the radical potential of art to set adrift mobilities of thought and action. In the house’s downstairs room, the three learn how to read aloud, their voices releasing words that carry their listeners towards somewhere else. Poetry is described as a place that never settles and its depiction as ‘a trembling thought’ recalling Glissant’s invitation to tremble with the world in all its opacity.[7] The trio fall asleep ‘softly floundering’ in the unknowing that poems bring, a sentiment echoed when the disordering power of music is described as that which ‘keeps us from thoughts of the system and systems of thought’.[8] BIOPIC is itself a poetic drift brimming with colour and texture, exemplified in wild handmade sculptural costumes and props including a ceramic milk-moat and finger-like egg holders that throw relationships with food into disorder. The mise-en-scène Bycroft creates is seductive and unsettling and the audiences may be ‘unmoored’ or (hopefully) challenged by their own sense of familiar logic when encountering the work.

The architecture of the Samstag Museum is such that at times the rich musical score in Bycroft’s film and women’s voices singing together in Alex Martinis Roe’s Our Future Network (2016) mingle in the grand void at the gallery’s centre. A reading room installed in Gallery 3 supports audiences to think with these artists by offering texts that bridge their complex research practices and provides further reference to politics of relation and difference. A screening of Bycroft’s preceding work the fouled compass (2020) shows a looping poetic script leading a sequence of experimental film from which pervasive concerns with the sea emerge. Martinis Roe’s book To Become Two (2018) is located alongside some of the texts and historical films referenced within it, providing an alternative in-road to her extensive research. I am particularly drawn to Margot Nash’s film Shadow Panic (1989) where a dreamlike atmosphere of seemingly wilful weather locates stories of three unconnected women, its circular narrative structure a complement to Bycroft’s work.

In 2014, both Martinis Roe and Bycroft undertook Anne & Gordon Samstag International Visual Art Scholarships. Martinis Roe went to Berlin where she began tracing her own feminist genealogy by developing a living archive of the practices that inform a position she describes as ‘solidarity-in-difference’.[9] Her commitment to Luce Irigaray’s writing on difference positions the work, with her instinct to trace a female genealogy perhaps a response to Irigaray’s attention to their neglect.[10] Through situated research Martinis Roe collects an expanding archive of relations including conversations, arguments and friendships between women. Using care as method, she identifies approaches to being in relation, providing radical alternatives to dominant androcentric modes of work and community under patriarchal capitalism. She describes this work as being a little like falling in love; she can be seen on screen, directing video from the inside while engaging closely with others.[11]

The relationship of ‘affidamento’, exercised and discussed since the 1970s within the Milan Women’s Bookstore co-operative is a politically radical relation of entrustment that involves establishing committed support between women so that each might in their own ways, further themselves within the patriarchy.[12] Martinis Roe spent time at the co-operative amongst other feminist collectives in Barcelona, Utrecht, Paris and Sydney to learn how, in practice, these relationships of entrustment are formed, and to take part in the practice of ‘giving the other authority’. The situations instigated and documented, and the objects collected, became the Samstag Museum work that exceeds the exhibition framework to form an inchoate archive and an expanding feminist network into the future.

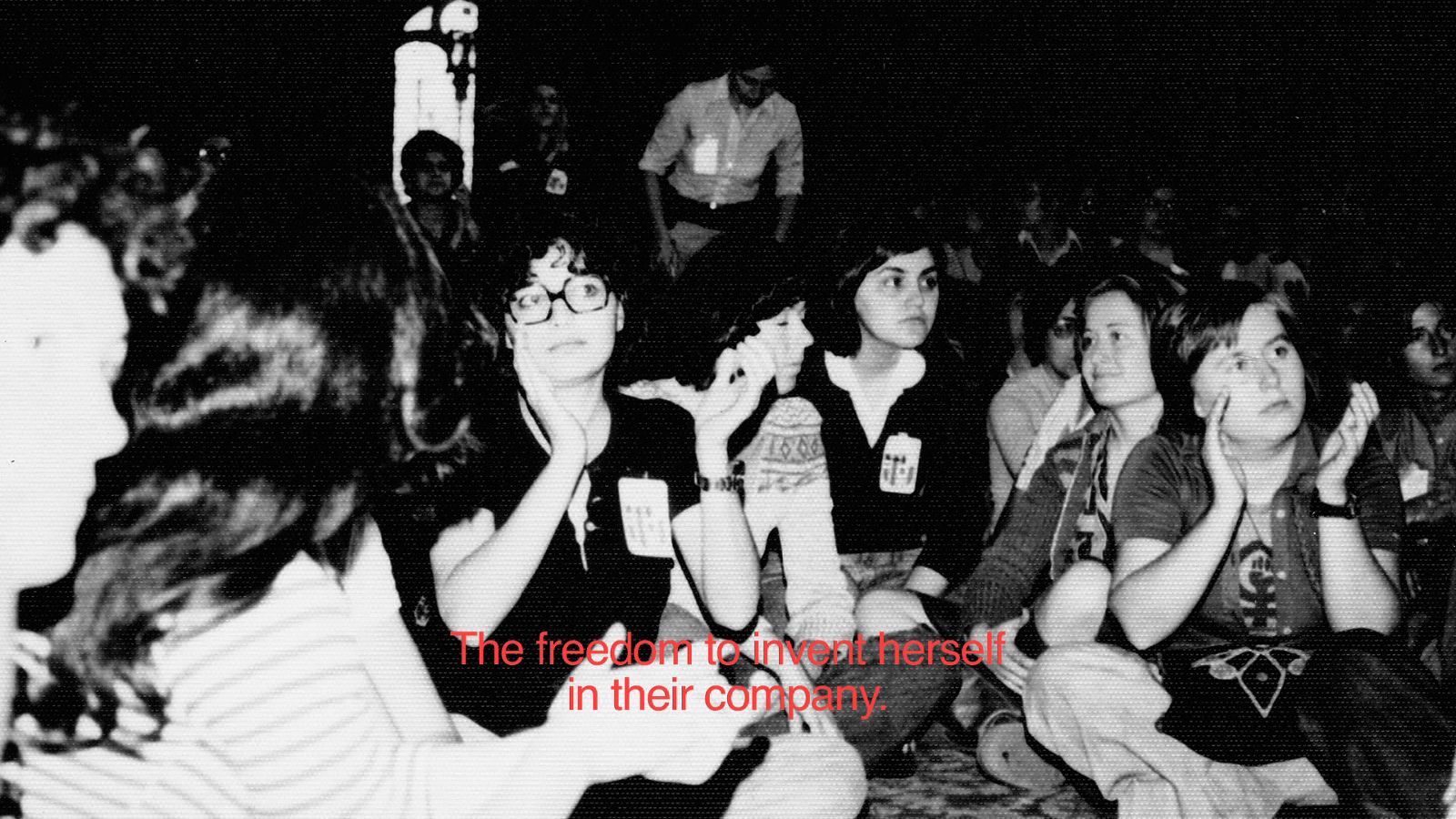

Navigating among artefacts, visitors to the space animate histories along their own chosen trajectories, enlivening and re-thinking events, informally repeating Martinis Roe’s work with the collectives. 'It was an unusual way of doing politics: there were friendships, loves, gossip, tears, flowers...' (2014) involves a script based on interviews recalling the meeting of 300 women at La Tranche-sur-Mer, France, in 1972, with footage recorded in Super 8 film and HD digital video. The work was performed by feminists and queer activists loosely re-enacting found film from the historic gathering. This reflective act of long memory activates bodies and forms relationships (both now and through history), where collective re-articulations ‘correct’ archives of omission.

The soundtrack to Martinis Roe’s Our Future Network (2016) can be heard across the gallery space overwhelming quieter screens and domestic objects. The propositions for feminist collective practices described within are invitations to (and practical guides for) generating shared futures. Perhaps because of the great shuddering mansion depicted upstairs, I am drawn to the discussion of ‘architectures for encounter’. This proposition considers how spaces are entangled with material politics and how they influence the arrangement of bodies, relationships and speech. I am reminded of the character Charlie in BIOPIC who struggles restlessly with the challenge of how to place their body in an anchored colonial architecture. Martinis Roe’s proposition outlines counter-strategies such as designing spaces open to different actions and exceeding the buildings’ original uses. Accordingly, polyvalent structures fill the installation space in the form of visually porous metal room-dividers to encourage multiple viewing pathways. Amid the installation is a pile of posters with the text OUR FUTURE NETWORK, an infinite edition and a familiar strategy in contemporary art shows. As I pin it up on a wall at home, I feel myself becoming a node extending the ever-expanding reach of this work.

Martinis Roe writes of a correlation between the emergence of feminist collectives and share-house living (in 1970s Sydney), where successful co-habiting compels working on relationships lovingly.[13] The practice of listening is discussed as part of the reciprocal act of speaking, critical to forming decentred understandings of the self.[14] In BIOPIC, identities are multiplicities that are unstable and not fully knowable (even to the self)—‘I think I might try Blue, as a name’ says Charlie-becoming-Blue at the film’s conclusion. I think of these two exhibitions by Martinis Roe and Bycroft as wonderfully different co-tenants that meet around their investment in complex identity cultures and ways of approaching politics of difference. Taken together, the artworks provide practical and poetic ways of countering fixed or reductive identity politics and conventional hierarchical relations.

With its six-month ‘season’ To Become Two allows repeat visits appropriate to the density of the research, further enhanced by workshops, talks and a feminist film program. The work has shown in the UK, Europe and Australia attracting extensive written responses, but it is iLiana Fokianaki’s thoughtful catalogue essay which so affectively positions Martinis Roe’s care-full methods as reparative acts against patriarchal systems. These exhibitions were preceded by Irish artist Jesse Jones’s installation Tremble Tremble[15] in which incantation called up feminine rituals and prompted covens to generate new female-centred law. These magical (Jones) careful (Martinis Roe) and wild (Bycroft) ways of living and being otherwise indicate refreshing and timely programming at Samstag, forming a non-traditional family of alternative knowledges from female and queer experiences.

Footnotes

- ^ Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 11-22.

- ^ https://womenshistorynetwork.org/charles-genevieve-louis-auguste-andre-timothee-deon-de-beaumont-1728-1810/; accessed 20 August 2021.

- ^ BIOPIC or Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée, Director’s Statement, Madison Bycroft, 2021.

- ^ Madison Bycroft, email to the author, 10 August 2021.

- ^ Claire Fontaine, The Human Strike has Already Begun & Other Writings (Leuphana University and Mute Magazine: the Post-Media Lab, 2013), 27-35.

- ^ Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: the disorder of desire (Duke University Press: Durham and London, 2020).

- ^ Glissant, 111-120.

- ^ Text from the film dialogue, BIOPIC or Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée (2021).

- ^ Alex Martinis Roe, To Become Two: Propositions for Feminist Collective Practice (Archive Books, 2018), 49.

- ^ Luce Irigaray, Je, Tu, Nous: Towards a Culture of Difference (Routledge: New York and London, 1993).

- ^ Alex Martinis Roe in conversation with the author, 21 July 2021.

- ^ Martinis Roe, 55-58.

- ^ Martinis Roe, 108.

- ^ Martinis Roe, 277.

- ^ Tremble Tremble was shown in Samstag’s 2021 Adelaide//International, the second in a three-part, biennial series aligned with the Adelaide Festival (2019, 2021, 2023).