The circus comes once a year, Lily

Then we gotta go

So come and laugh a while Lily

Come and join the show

“Hi Lily Lily Hi” Carnival Song, Tim Buckley

The English translation of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables is only one of several translations I’m told. Beyond the admirable central character, there are The Miserable Ones, The Outcasts, The Wretched Poor, The Victims or The Dispossessed. They are exotic people from exotic places; fairy-tale people from fairy-tale places. In the Australian context, this could describe both Aboriginal and carnies, the precarious dirt poor surviving on their physical talents, providing thrills, joy and warmth vicariously to their audience.

In art imitating life imitating art, The Dickensian Circus of Karla Dickens unfolds in three parts from three entrances in its Lismore appearance. Collating parts from her loved Adelaide Biennial installation with new pieces from Lismore’s recycling centre, a carnival of wonder, of sweet and sour, rolls out. As you come up the stairs a playful children’s façade theme park type entrance welcomes you; cute but embedded with racist stereotyping from the moment you pass through the barrier into an area filled with Warner Bros cartoon characters. A Warner Brothers Porky Pig in a police hat innocently smiles but jars as you become aware of its label Warn a Brother and Lawless Piggy. We find large blow-ups of a series of weird postcards of black and white children around the age of four in boxing gloves and poses, black eyes and scenes of white supremacy with racially stereotyped black boys and men.

These images are powerful in the thought that they were once seen as cute and playful by a certain section of society. They introduce us to the hard life side-show alley boxing troupes where many Aboriginal men earned a crust. I read somewhere that there are eighty-six billion neurons in the human brain but that “trace memory” neurons track specific information. And that, in recalling information–memory, sets of neurons interact and collaborate so to speak to recreate the memory-based sensory and emotional image. There is a theory that memory and personal traits are also stored outside the brain in the heart and other organs as a kind of embodied memory.

Moving through, the main room opens to a menagerie of objects, signs, jam jar labels, toys and other found objects carrying other people’s shadows from other people’s lives. A strong path of Australiana runs through the hundreds of amazing, differing magical things that catch your eye here and there, but shimmer with emotional response.

“Peter’s Ice Cream – The Health Food of a Nation.”

The main gallery also continues the salt and sour theme just slightly out of sight with one side presenting fragments of our awkward, poverty-stricken traumas with a heavy theme of Australiana, an Australiana of people and things left behind as junk and ditched to the side of the road; objects that seem familiar, even joyful, but are now darker and have lost meaning as we’ve grown older or moved away. A set of marsupial species, a Koala and a rocking-horse Kangaroo (LIVE STOCK), are wonderful to behold, but as we know the actual native species will possibly be extinct within our lifetime due to complete neglect.

“A Bloody Good Business and a Bloody Good Life”, Jim Sharman

On the other side of the door are a set of silver and gold boxing gloves mounted on rods a metre high that appear dream-like as rising serpents from a Greek myth, as Theatres of Power. Recently departed and loved local Bundjalung artist and one- time side show boxer Digby Albert Moran, Elder, Artist, Boxer, is remembered here with his side show drum. A double practice of colonisation was the rubbing out of this historical record of the Aboriginal presence and of Aboriginal people attempting to keep our history in societal memory. We now know more of the cost of poverty associated with putting their lives on the line. Up to ninety percent of boxers are known to be suffering from brain damage and memory loss.

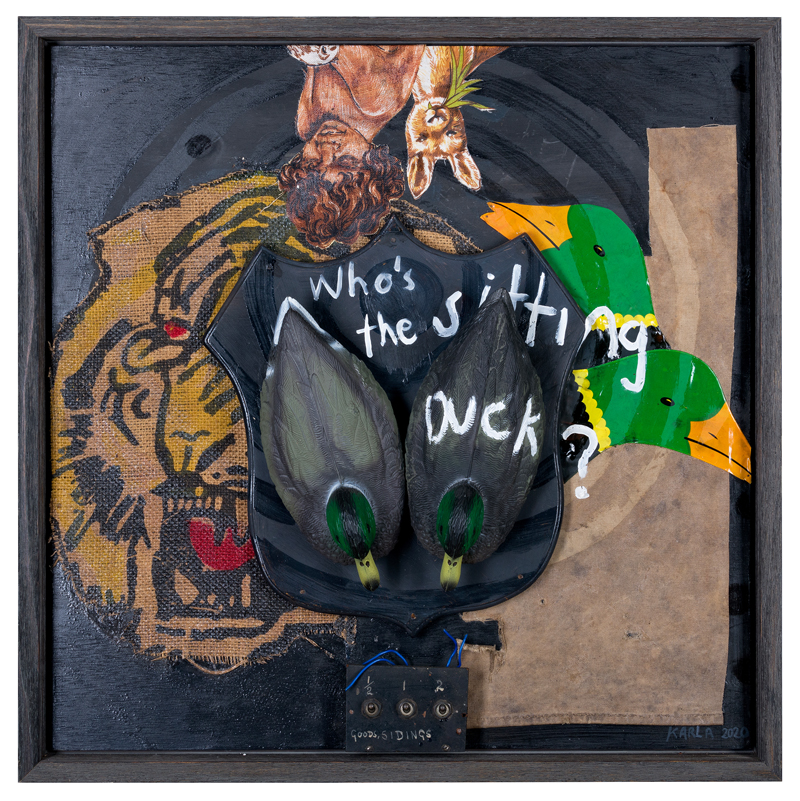

I thought of Karla’s surreal installations and constructions here as being akin to two movements through the dream trauma cell enclosures of great feminist artist Louise Bourgeois and bird cages that abound within Karla’s installation. Here, as the direct use of the found object, they are both loosely arranged and gathered and formally framed in a set of Schwitters-like collages that make up the back wall: Johnny on the Spot, Who’s the Sitting Duck and so on.

In 1938 Aboriginal activist William Cooper led the Aboriginal Advancement League in protesting to the German government over the treatment of Jewish people after Kristallnacht. Aboriginal people of course were also suffering in the 1930s. Here, featured in a single side room is a beautiful 1930s woman’s motherly voice and the sexy joyful moving images of Lismore-born Con Coleano (Cornelious Sullivan) the Greatest Tight Rope Walker in the World.

Although famous and acclaimed, Con avoided revealing the fact of his Aboriginal descent due to the problems this would cause as Aboriginal people were still non-citizens. Two large declarations fill one wall opposite the entrance: a large floor-to-ceiling pennant with Lismore and Bundjalung in large running writing letters next to it fix us to place and Aboriginality, to who we are and to where we are. The one place without hidden fear. Here we bathe in the warm joy and glow of beautiful Con, sister, and wife, as they effortlessly create impossible athletic feats.

I see the whole collection of Karla’s cross material objects, audio, and historical moving image as a one-piece powerful engaging artwork that engages on so many levels and should be in a collection somewhere. It will also be shown in Orange Regional Gallery later this year and is a “must see” exhibition.