.jpg)

Riot: an instance of “unrestrained revelry” that threatens to “disturb the peace”, a “disorderly profusion” that is at times “wildly amusing”.

Merriam Webster Dictionary

FEM-aFFINITY is a riot of form and colour, celebrating diverse experiences in playful provocation to exhibition-making norms. It presents the work emerging from a six-month collaboration between fourteen female-identifying artists, seven from Arts Project Australia—a centre of excellence in Northcote, Melbourne, that supports artists with an intellectual disability—and seven “non-marginalised” contemporary practitioners. Curator Catherine Bell has a long track record in community-based participatory projects and a close working relationship with Arts Project artist Cathy Staughton.

Motivated by the desire to “shift the discussion away from disability and focus on the artistic interests, aesthetics, processes, and social interactions of the Arts Project studios”,[1] Bell facilitated the creative interactions between the two groups of artists, pairing Staughton with Prudence Flint, Jane Trengove with Fulli Andrinopoulos, Helga Groves with Wendy Dawson, Eden Menta with Janelle Low, Dorothy Berry with Jill Orr, Lisa Reid with Yvette Coppersmith, and Bronwyn Hack with Heather Shimmen. Herself an artist, Bell was guided in her choice of participants and the eventual selection of works that spoke to the shared experience—alongside existing works that contextualised the new responses—by a fluid notion of affinity, one based on feminist principles of collaboration, questioning established categories and hierarchies of practice, to acknowledge that voices and identities are shaped by these interrelations that are always in the process of becoming.

The final exhibition clearly reflects these principles. It is hung so as to activate as many correspondences (or affinities) as possible, not just between the collaborating artists. Works by each pair are installed adjacent to each other, but there are at least two contributions by each artist so that an ongoing dialogue is created—a painting in the back gallery pinging back to a photograph in the front to reconfigure the conceptual and formal links. This is one way in which the sense of a riot is invoked, but the appeal of such random profusion is by design. Another is through the changes in scale and medium throughout the exhibition, where intimate and informal life drawings or family snaps are interspersed with large-scale, slickly finished paintings, where floor to ceiling prints are set off by tiny abstract doodles, where works distinguished by their purity of line or colour punctuate performative photography.

Each work reaches out to the others, across time and space and medium, testament to the relationships between long-term studio neighbours, the spark of newly formed creative partnerships, and the generous and intelligent facilitation by Arts Project and Bell. This is not just curatorial balance: it underlines the relational nature of the works and processes on show. FEM-aFFINITY embraces the feminist ethics of care, understood as an alternative to the moral imperative based on the injunction to respect the rights of autonomous individuals. The moral imperative of care by contrast is based on relationship, on nurturing, and a responsibility to “alleviate the ‘real and recognizable trouble’ of this world”.[2] Care is evident in all aspects of FEM-aFFINITY.

An ethics of care could also be said to underpin the Arts Project studio, which over its forty years has created a community of artists supported by arts workers of long-standing. The productive energy in the studio is fuelled by acts of intense making and companionship—of great appeal to artists, who occasionally rue the solitariness of the private studio. Such riotous creativity can loosen established ways of making, issue license to experiment and take risks, as several non-Arts Project artists, including Prudence Flint, Jane Trengove and Helga Groves, experienced. They confided in the curator that the collaboration had led them to reflect on their own approaches and processes; in particular, it had thrown into sharp relief their own inner censor that in a patriarchal world can be redoubled by internalised gender expectations. Inspired by their collaborators, and the collective free-wheeling, these artists found themselves taking unexpected turns.

Flint’s fast and furious sketches of a couple in various erotic entanglements is a great example, giving free rein to impulses more often placed under tight control in her carefully constructed compositions. Sexual desire and sensual pleasure are also activated in the dialogue between Flint’s paintings and Staughton’s responses: together, Cut on the Cross (Flint, 2013) and Catherine Bell Love Anne Baby Same (Staughton, 2019), unleash the repressed eroticism of the encounter between a woman and a dressmaker’s dummy. In Flint’s commanding Feed (2019), the breastfeeding mother appears determined and self-possessed, but alongside Staughton’s mother and child (A Man Doctor …, 2008), the latent riotousness emerges. This creative abandon appears in a different guise in the intimate scale and restrained palette of Trengove’s and Andrinopoulos’ minimal forms. Here the intensity is in the repetition of infinite nuance. The works were created in dialogue—one can imagine the meditative trance of a silent collective practice—but continue their interaction in the gallery: Trengove’s glowing spheres hover between two and three dimensions, between pure light and solid mass, their near-perfection brought back to earth by Andrinopoulos’ texturally expressive and rapid experiments. A similar exchange of energy animates the collaboration between Groves and Dawson. Groves’ intricate abstract paintings, in part inspired by natural geological formations and patterns, both stimulated and responded to Dawson’s concentrated mark-making, as mutually corresponding creative cues in rhythmic synch.

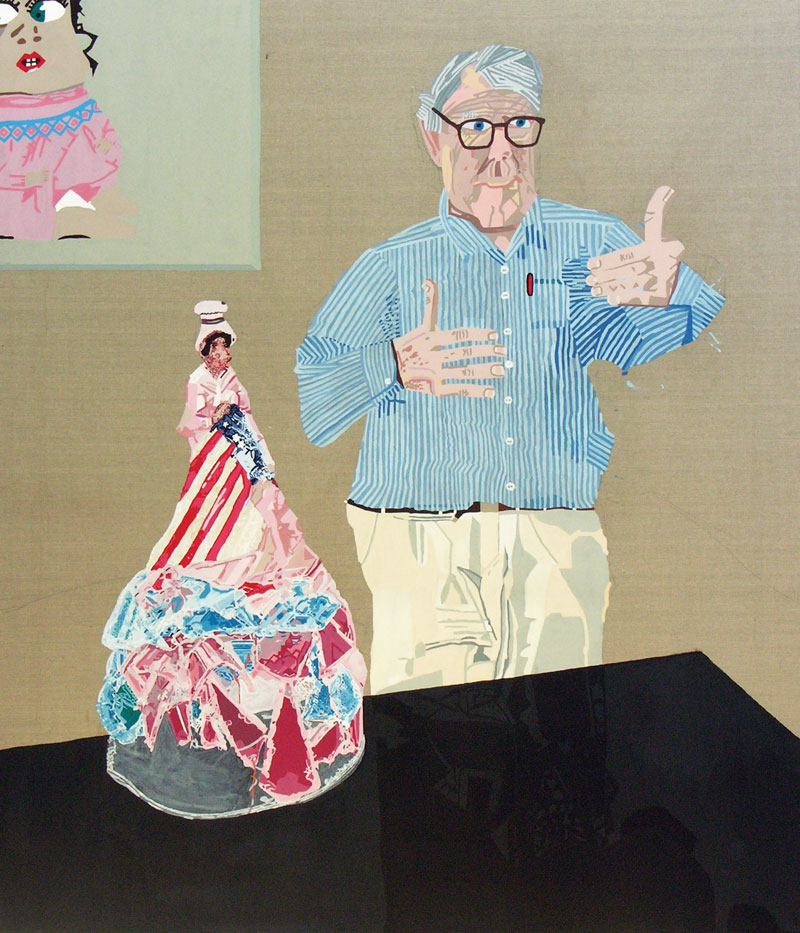

This erotic charge surges through the exhibition, setting upon and connecting unlikely works. Reid’s portrait of collector Peter Fay (2007)—a longtime supporter of Australian artists, particularly those who don’t identify as insiders—captures the subject’s infectious enthusiasm in his gesturing hands and bright eyes. The portrait shares further affinities with Reid’s life drawings and Coppersmith’s portrayal of a shirtless John Safran and a cool Mark Feary (John Safran, 2009, and Forever in Blue Jeans, 2007). In Reid’s striking pen and ink depictions of naked men of a certain age, detail of the striped fabric which drapes across the models’ bodies echoes in Fay’s preppy shirt, while vulnerable bellies find fleshy counterparts in Safran’s maladroit body. To me, these juxtapositions evoked Dani Marti’s video portrait of Fay (Bacon’s Dog, 2010), which achingly documents Fay’s first sexual experience in late middle age.

The power of vulnerability—as a form of resilience in remaining open to others and the world—is embodied in the cadavre exquis created by printmakers Shimmen and Hack. The wall-to-ceiling work stitches together body fragments harvested from the artists’ shared love of true crime and Gothic imagery to represent the monstrous feminine coursing with sexuality and laughter. The monstrous feminine as a kind of alternative ethics, not grounded in anthropocentrism, is also picked up in the animal–woman hybrids invoked in Orr’s performances such as Lunch with Birds (1979)—one of the few historical works in the exhibition, as the outcome of a pairing that did not involve actually working together.

It is a treat to see the full suite of the performance photographs in the original scale; like a series of horror film stills, Gothic skies included, they depict Orr beseeching the seagulls of St Kilda beach, body splayed as an offering of fish and loaves. Adjacent hangs a painting of a bird–woman by Berry (Not Titled, 2009,), whose use of bird motifs over many decades arguably amounts to a self-portrait. While Orr’s invitation for inter-species communion was ignored, Berry appears to inhabit the bird, a feat Orr got closer to in the stunning Antipodean Epic-Interloper (2016).

Photomedia artists Menta and Low, who first met as a result of this exhibition, are now firm friends and plan to collaborate on another show. That rapport is evident in the works here, glimpses of intimate moments shared (Eden in the Mirror, 2019) alongside photographic explorations of identity and sexuality (such as Low’s Untitled (self-portrait), 2013 and her poignant series of family portraits where the faces are blotted out with gold leaf). But perhaps what best captures this creative relationship and indeed the spirit of FEM-aFFINITY as a whole is the glorious Eden and the Gorge (2019), a jointly-authored inkjet print. Menta lifts her skirt to the Australian landscape in a gesture of freedom, joy and defiance that powerfully embodies feminist activist Audre Lorde’s definition of “the erotic as power”: “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them, and lessens the threat of their difference.”[3]

Guided by intersectional feminist principles, FEM-aFFINITY as a process and exhibition indeed “forms a bridge” to ways of feeling and thinking about contemporary art that unsettle existing categories.

Footnotes

- ^ Catherine Bell, FEM-aFFINITY, exh. cat., Melbourne: Arts Project Australia, 2019, n.p.

- ^ Maxine Ryder, Dorothy Berry: Bird on a Wire, exh. cat., Melbourne: Arts Project Australia 2009, p. 9__3 Audre Lorde, Uses of the Erotic: the Erotic as Power, Kore Press, 2000, first published in 1978.

- ^ Audre Lorde, Uses of the Erotic: the Erotic as Power, Kore Press, 2000, first published in 1978.