I like group shows. I get a kick out of the “open call” agricultural show displays and local art society exhibitions. I can be entertained by the efforts of institutions that stage subject or theme‑based exhibitions to reveal, explicate or interrogate the unique qualities of their collections. I even enjoy art prizes such as the Archibald, Glover, NATSIAA, Moran and Freycinet award exhibitions, that support the gambit of direct application by cultural producers. I also admit to some passing interest in the prize money and sponsorship rights. (Australia Loves a Winner!). In these exhibitions, wide-reaching critical notice and public acclaim is enmeshed with skilled marketing around socio‑historical cache and relevance.

It is this compounding series of juxtapositions – haptic, formal, serendipitous or merely convenient – that can stimulate new understandings of cultural production at a particular point in time and place. At their best, group or survey shows offer viewers the experience of an “archive in transition” (Harald Szeemann) and a heady form of “cross‑pollination” (Hans Ulrich Obrist).[1] These rewards are central to the appeal of The National sounding much like a horse race (like the rogue element of Elizabeth Taylor’s entry into the great British steeplechase, also known as “The National” in the 1944 film). At Carriageworks, the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the Museum of Contemporary Art, curators Clothilde Bullen, Anna Davis, Daniel Mudie Cunningham and Isobel Parker Philip have worked collaboratively to present 70 artists across three venues.

Now in its second iteration the program was developed to counter the rise of Melbourne, Brisbane and Hobart as major cultural destinations, also to trumpet Sydney’s continued pre‑eminence in its support of contemporary Australian art. As the distant spawn of the Australian Perspecta (1981–99), The National is a group show of the “Zeitgeist trawler” type. Like the more globally ambitious Biennale of Sydney and the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, these exhibitions offer audiences an encyclopaedic (empirical, objective, universalising) and also idiosyncratic (political, experiential, empathic) snapshot of current agendas.

The National 2019 creates what perhaps is now a gap in the market for something more truly home‑grown, driving a sense of community and creativity through its expansive invitation. Feel‑good elements are balanced with timely political instruction (relevant to this hovering mandate of the “national”) to create an edgy and exciting crowd pleaser. I applaud the curators assigned to produce these behemoths. They juggle the demands of the marketing department, current ideas of institutional profile and philosophy as well as the idiosyncratic nature of the available exhibition spaces, and of course the pulling‑power of the artists themselves. It is well‑known that curators often become surrogate counsellors corralling artist’s expectations, as well as travel agents and advocates for further funding from public and private sources. The valuable research and discernment of qualities in the artwork selected also can be seen to blaze a path for future commissions and opportunities. It is to be hoped that the host institutions will also do well through the significant bump in audience numbers.

The National 2019 curatorium claim that their show is like the second child in a family “a bit rogue” and “our little rebellion”. [2]That may be pushing it a bit far, as the most radical element is the gender breakdown: 43 women, 27 male artists. In spite of the desire for “a third space” of experimentation and “different conversations”, there is a familiar 21st‑century earnestness to much of the work and the quality is varied (an outcome, as previously stated, of the group show effect). Here, there are many instances of the Over Literal and Over Egged, as well as the Unformed and the Severely Encoded by Higher Degree juxtaposed with some wonderful, provocative and possibly sublime pieces to subtly reconfigure the Australian cultural landscape. And, to this extent, the curators have chosen well.

Thresholds to each exhibition space reveal the lie of the land. Mudie Cunningham goes large for maximum impact at Carriageworks (the former Eveleigh Railway Workshops), providing the opportunity for artists to respond to the industrial heritage of the site. The hegemonic ideals of modernism are ironically referenced in the billboard‑scale train/person portraits of Thom Roberts, the milky steam environment by Tom Mùller and the Ken Done‑style sign Utopia by Sam Cranstoun. Parker Philip elegantly underlines the empty power of the Temple (History, Classicism and the Enlightenment vision) in the vestibule and grand entrance hall of the Art Gallery of New South Wales with the placement of multiple dissected portrait busts of an unknown Italian noble by Andrew Hazelwinkel, while enormous curtains lift to reveal dissembling humanoid forms on protest placards painted by Tom Polo. “Look at Me!” they demand.

(3 parts), 2019, powdered pigment, gypsum cement, mild steel. Installation view, The National 2019, Art Gallery of NSW. Photo: Mim Stirling. Courtesy the artist and Reading Room, Melbourne

At the Museum of Contemporary Art, Bullen and Davis throw audiences headlong into a consideration of origin stories, the primordial cultural forces, particularly noteworthy in works by Curtis Taylor, Tina Havelock Stevens and Hannah Brontë. Taylor’s grotesque museum vitrine with perfectly lit disembodied tongues writ with crudely carved language is one of the most powerful statements of colonial destruction and survival of indigenous cultures. Havelock‑Stevens and Brontë re‑present the chthonic as ultimately positive affirmations of self and community.

The themes of the mutable natures of History, Gender, the Self and Materiality weave throughout The National 2019. Izabela Pluta’s epic photographic installation Apparent Distance at the Art Gallery of NSW is a bravura synthesis of her work to date. Exploring once again the origins of ruins, sham or otherwise, and the processes of their displacement through unveiling alternative archaeologies of truth, memory and the experience of place. The viewer is taken to Yonaguni Jima, an island in the Ryuki archipelago 120 kilometres from Taiwan where in 1986 a local diver discovered what looks like submerged architecture.

The sandstone structures are logically explained by current geological frameworks, but many think that these stones are the remains of Mu the Atlantis of the Pacific. The viewer is placed on the edge of land where all is in flux. Various scaled photographic images are combined with architectural punctuation points on aluminium panels leaning against the wall. The images depict a cliff top fence line, a child’s soccer ball trapped in the rocks, the ocean and the flotsam and jetsam that remains. Interestingly, the site has been renamed Ruins Point, Iseki Hanto.

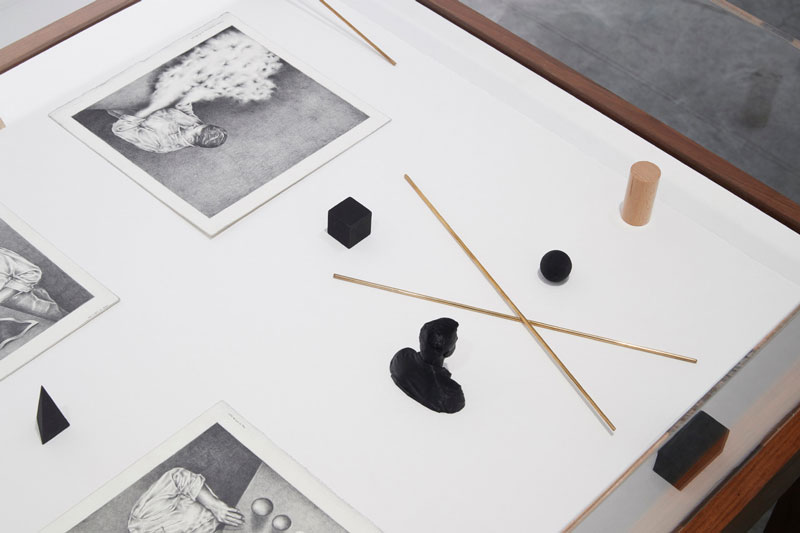

At the MCA, Julia Robinson’s sumptuous and sexy, sewn, stuffed, padded and braided forms dance across space reminiscent of 1930s surrealism as well as the Arcimboldo‑like plant forms and hyperbolised fragments of Elizabethan costume and Kandinsky’s painted abstractions. Similarly, in The Black Captain Teo Treloar re‑purposes motifs from Albrecht Durer’s Melancholia (1514) for the 21st century in a series of meticulous and extraordinarily detailed pencil drawings. Rather than an androgynous angel with an epic case of thwarted creativity, the classic writers block, Treloar employs the figure of a middle‑aged businessman with a white shirt and encroaching paunch to search the dimensions of visual reality. He is locked into a nightmarish Moebius strip of imagination, creation and distillation. There is no way out and no languages to redeem this landscape of infinite pointless production that is neither representational illusionism nor abstraction.

The installation dis(order) by Eugenia Raskopoulos features a neon pendulum flashing the title of the work. In the scheme of things this element is superfluous. Opposite this alcove is a single‑channel projection of a performance made in situ at Carriageworks, the roughly painted surface of this industrial space giving the appearance of looking into an old mirror or the flickering of a Super8 home movie. A silver‑haired woman dressed in black operates a boom lift cage. The woman (Raskopoulos) slowly places familiar labour‑saving devices – a washer and dryer, microwaves, toasters etc. – on top of each other to create a Jenga‑like accumulation of white goods. Then the process is just as carefully reversed with each item from the tower of household appliances dropped from a great height. The documentation feels like a homage to women artists of the 1970s, such as Mierle Ladermen Ukeles. This is a transgressive but also hilarious feminist critique of consumerism and the instruments of domestic oppression.

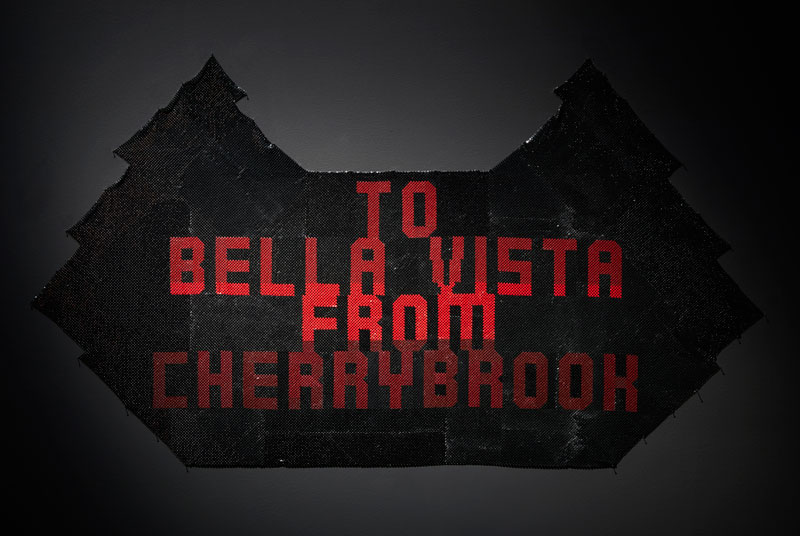

Postcards (2010) by Troy‑Anthony Baylis similarly subverts the wearing of breastplates endowed by the British settlers on the Indigenous population during the nineteenth- and early‑twentieth centuries. Featuring queer cloaks of silver and gold, Bayliss explodes this richly ambivalent heritage of honorific apparel. Inscribed with texts such as “To Crystal Brook From Sandy Gully Via Alice Springs” or “To Nelly Bay From Mona Vale X” the work honours the existence of Blak Queens and Sista Girls as shape shifters. These shimmering monuments in motion are made with tiles from vintage Glomesh handbags purses, cigarette and glass cases, make‑up compacts etc.

I am reminded that Glomesh ensembles of halter‑neck top and a matching handbag, worn by glamorous hostesses from Sale of the Century, who were the height of fashion in Australia in the 1980s. Glomesh was made by Glo International of Sydney a company founded in 1958 by Hungarian immigrants Louis and Alice Kennedy. The company also made pieces in the less showy hard enamel colours of beige, black and bronze that were more suitable for day wear. I am sure Baylis appreciates the alternative name of breastplates as a form of decorative armour, the gorget.

James Nguyen’s Portion 53 on exhibition at the MCA was for me the most successful work in The National 2019. This three‑channel video installation modestly placed in a hall between two larger galleries is a collaboration with the artists’ parents and composer Kezia Yap. Not that there is much recognisable music only the sounds made by insects in high summer, perhaps the trace noises made by rubbing Polystyrene together. This plastic, along with all types of trash and asparagus weed, has infested a site that was once an Indigenous settlement of the Dharawhal people up to the early 1950s when the land was taken over by the Australian Army and later made into the East Hills Migrant Hostel. Nguyen’s father speaks (English, subtitled in Vietnamese) in shocked tones to the architectural remains that stand in for his family’s first experience of Australia, after fleeing Communism in Vietnam and a refugee camp in Indonesia.

These scenes of the artist and his family cleaning up the rubbish they discover are accompanied by a poem, recited by Nguyen’s mother (Vietnamese, subtitled in English), composed after learning of the Indigenous history of the site, also in reflection on its later gentrification as Voyager Point. Her poem concludes:

33 years since your removal,

My family came.

housed on this patch of beloved soil

I don’t have to think so far,

to feel a loss,

and think how my new life,

owes much to your ancestors

Granted a peaceful refuge

My Gratitude.

Such respect is overwhelming and transformative, as with the best of the art that The National 2019 delivers.

Footnotes