(1).jpg)

In the grand surroundings of the Royal Academy, Oceania makes the intentions of its curators clear from the start. While it includes artefacts from the great collections of Europe and beyond, this exhibition is not about consigning the creativity of Pacific peoples to the past, and neither is it interested in viewing these objects through an ahistorical primitivist lens. This show is about a living past, and the vibrant present. The visually momentous Kiko Moana, a representation of the great Moana, the ocean itself, runs floor to ceiling in the opening gallery. It is a work woven and sewn from polyethylene fibre by the Mata Aho collective: Elena Baker, Sarah Hudson, Bridgit Reweti and Terri Te Tau. Its blend of traditional skills and contemporary synthetic material speaks of the endurance and adaptability of the cultures depicted here. This piece from Aotearoa New Zealand, and its position in the exhibition, also indicates the role of the ocean in linking the otherwise far-flung islands of the Pacific. This understanding of the ocean, as the unifying link in the contemporary Pacific, was articulated by the great Tonga thinker Epeli Hau‘ofa when he wrote that what Pacific peoples have in common is that “the ocean is in us”.[1]

Just as the ocean is home to the cultures seen here, it is paradoxically also the single largest threat to life and home in the age of anthropocentric climate change. Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, who came to world attention when she addressed the United Nations in 2014 with her poem “Dear Matafele Peinem”, is shown reading “Tell Them”, a poem about life in the Marshall Islands, which finishes with a stark account of how the ocean threatens the capacity of the islanders to stay on their islands: “tell them/we don’t want to leave/ we’ve never wanted to leave/ and that we/are nothing without our islands”. For the ocean is indeed home but because of almost two hundred years of unchecked industry elsewhere, it is rising at a rate that is already making life untenable on the atolls of Jetnil-Kijiner’s home. This is a salutary context from which to view the rest of the exhibition, a reminder that the time in which action can be taken is limited. The other striking thing in the first room is a large map of the Pacific showing all of the island groups. It is a rare thing to see this vast region depicted in its entirety without a line through it, or on the edge of more powerful places. Almost all of the island groups are shown here, and to emphasise the importance of this, the guide to the exhibition features this map on its reverse side as well. It may be the first time most visitors to the exhibition have seen Oceania mapped in this way, as its own entity.

These understandings at the start of the exhibition – Oceania as a discrete and specific zone, the incorporation of tradition into contemporary art and vice versa, and the Pacific’s current state of environmental threat – provide the context in which these treasures, these taonga to use the Māori term, are to be understood. The curators, Peter Brunt (Aotearoa New Zealand/Samoa) and Nicholas Thomas (Australia/UK) undo European divisions of Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia in favour of linking Oceania through the foci of “voyaging, making places and encounter”. The region was populated by masterful acts of ocean voyaging and the two navigational teaching charts from the Marshall Islands remind us of this, as do complete canoes from Papua New Guinea and the Solomons, carved Māori prows and sternposts, and a range of delicately carved oars and paddles from across the region.

An instance of continuity across Oceania is the juxtaposition of a Tahitian “sculpture of two double figures and a quadruped” (1690–1730), and a very early and distinctive Māori sculpture, Tangonge, the Kaitaia carving (1300–1400), which was found in a swamp in 1920. The similarities in style are unmistakable. Tangonge, named after the place it was found, features a tiki grasping the tails of two creatures, possibly taniwha; it expresses not only unity but a profound and powerful symmetry. Over recent years Tangonge has been displayed locally at Kaitaia, in the north of the North Island, reportedly becoming “‘an essential element for the community development of our whānau and hapū’ (families and clans)”.[2] If the impact of this taonga on community in its local setting has been so profound, what might be the impact of returning other objects seen here? While a few of these treasures have been loaned from institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand, the majority, well over half, have come from museums in the UK and Europe, and most were collected during the period of active colonisation.

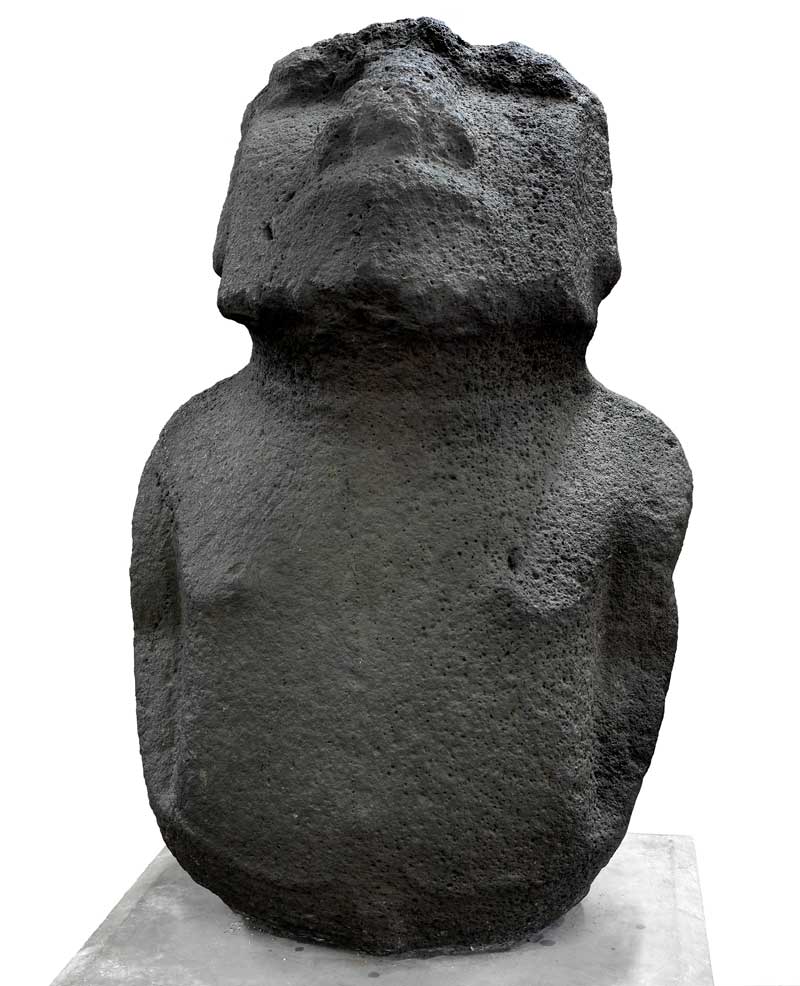

In August, the British Museum received a request for the return of Hoa Hakananai‘a, a rare basalt moai from Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Its counterpart, Moai Hava (c. 1100–1600), collected at the same time (1869) by HMS Topaze, when the community on Rapa Nui was devastated by disease and enslavement, is seen here, its upturned face, despite the wear of time, capturing a delicate poignancy rare in such a large object. The Rapa Nui have offered to replace Hoa Hakananai‘a with a basalt replica in order to ensure the return of a moai that is “a brother,” according to Anakena Manutomatoma: “Once eyes are added to the statues, an energy is breathed into the moai and they become the living embodiment of ancestors whose role is to protect us.”[3]

While many museums have opened their collections to visits by members of communities from whence the objects originally came, the notion of returning them remains contentious. Te Papa in Aotearoa is one institution where there seems to be a balance between making its collections accessible to community members while providing the curatorial care many treasures require for longevity. Some communities, such as Tonga, one the exhibition’s sponsors, have not been able to maintain a national museum in which to keep such precious objects. Employing curators from the cultures represented is one step toward opening collections, and interpreting them with respect; much of the insightful recorded commentary provided on Oceania’s audio guide comes from Maia Nuku (Ngai Tai), from the Metropolitan Museum NYC.

Almost as if to counter such thinking about repatriation, the curators are at pains to stress that most items seen here were gifts from cultures in which giving is an integral part of social exchange. This acknowledges the agency of the givers in making strategic exchanges, but it does not necessarily negate the question of repatriation. There is one notable treasure seen here that was known to have been stolen. A seven-metre-long feasting trough in the shape of a crocodile was taken, with many other items, from Kalikongu village in the Solomon Islands, as part of a series of retaliatory attacks by British naval officer Captain Davis in 1891. Davis claimed it had been used in cannibal feasts, thereby endowing it with the frisson of “savage” practices, and increasing the price when he sold it, even though those in the area did not practice cannibalism.

Some of the most reflective, powerful and exciting contemporary art worldwide is emerging from the Pacific region right now, much of it informed by deep engagement with the archive. Fiona Partington, Yuki Kihara and Lisa Reihana are three artists who exemplify this practice, and examples of their work are seen toward the end of the exhibition. This includes Reihana’s masterful video work In Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, displayed across 22.5 metres of screen, and showing concurrently at Brisbane’s APT9. Appearing in different versions over the past decade, it engages with the French wallpaper Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique (c.1804-06); both show dazzling technicality for their times and push at the possibilities of their mediums. Instead of the classically draped “noble savages” of the original, Reihana has employed a small army of Pacific performers acting out scenes from daily life and from the Cook voyages, which set out 200 years ago from Plymouth, and is part of the inspiration for this show.

![Lisa Reihana, in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17 (detail), single-channel video, Ultra HD. Collection: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2014. Additional support from Creative New Zealand and NZ at Venice Patrons and Partners. © Image courtesy of the artist and ARTPROJECTS](/uploads/articles/Oceania_5(1).jpg)

The scenery rolls from right to left, and critical moments to Europeans, such as the death of Cook, occur away from the central part of the screen, altering their presumed importance. The viewer is also guided by the soundtrack coming in and out of earshot, on which can be heard a range of Pacific languages, as well as the sounds of performances and even Cook’s original chronometer. The soundtrack is a startlingly complex achievement on its own. There are inside jokes and challenges to accepted histories. The chanted “fai fai pea” from Samoan-New Zealand hip-hop artist King Kapisi’s hit ‘Screems from da Old Plantation” (2000) can be heard at one point; on one 32-minute loop, Reihana presents us with a transgender Cook; the next time through the figure is cisgender male, thereby gesturing toward the range of gender identities possible in traditional Pacific life.

Many aspects of the exhibition are in conversation with each other. Tupaia, such an important figure on Cook’s first voyage, returns as a character in In Pursuit of Venus [infected], discussing science with both Cook and Banks. He also emerges from the archive as an artist himself, for while he had been known as a master mariner who charted the seventy odd islands he knew, it was not until the 1990s that a letter, written by Banks, identified him as the painter of several watercolours, all demonstrating his precise eye for detail. It is one of the wonders of this exhibition to be able to view his works.

.jpg)

Fiona Pardington engages with phrenology, part of the racial “science” of the nineteenth century, in photographs of life masks made by Dumoutier on d’Urville’s second voyage, reclaiming from the depths of the Musée de l’Homme the faces of Pacific Islanders including her ancestor Matoua Tawai. Yuki Kihara’s video work Siva in Motion (2012), now also in the collection of Brisbane’s QAGOMA, draws on a range of sources. It is a memorial to the tsunami of 2009 that killed more than 179 people in Samoa, American Samoa and northern Tonga, as Kihara, in the persona of Salome, performs the taualuga, the final dance of any important event. In its multiple layers, the work evokes the nineteenth-century experiments with moving image by Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey, producing an extraordinarily moving piece that runs for eight minutes and fourteen seconds, the length of time the tsunami took to bring destruction. Salome herself is drawn from the archive, a contemporary embodiment inspired by a colonial photograph, brought to life in several of Kihara’s works as a figure of memory and mourning.[4]

The exhibition has been hailed as a blockbuster. It makes its mark by presenting an astonishing range of treasures from Oceania and by making no division between “artefact” and “art”, showing a continuum of art practice over hundreds of years that continues to grow in strength and depth.

Footnotes

- ^ Epeli Hau‘ofa, We Are the Ocean: Selected Works, Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008, p. 58.

- ^ Haami Piripi, chair of Te Rūnanga o Te Rarawa, quoted in Peter Brunt and Nicholas Thomas, Oceania. London: Royal Academy Publications, 2018, p. 281.

- ^ Quoted in Jasmine Weber, “Easter Islanders Are Visiting British Museum to Request Repatriation of Ancestral Heritage”, Hyperallergic 16 November 2018: https://hyperallergic.com/471701/easter-islanders-are-visiting-british-museum-to-request-repatriation-of-ancestral-heritage/.

- ^ For a fuller account of Kihara’s Salome and her origins, see Madeleine Seys & Mandy Treagus, “Looking Back at Samoa: History, Memory, and the Figure of Mourning in Yuki Kihara’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’ Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas, 3.1–2, 2017: pp. 86–109.