Along with other anachronistic histories of the future like the flying car and the robot butler, the human hybrid with the massive helmet and gloves is back, although the goggles used now are smaller than those unwieldy headsets that turned humans into techno-monsters. Two years ago I experienced a new craze in Mexico City — a virtual reality party organised by Gibran Morgado of VNGravity.com. Like those ubiquitous images from the 1950s of cinema audiences with 3D specs, the sight of half the attendees wearing VR goggles and balancing drinks evoked a “Back to the Future” moment.

For those who have followed VR since the 1990s other technological advances have changed the landscape. Michael Heim (author of the classic Virtual Realism in 1998) points this out in his recent book VR Third Wave, which explores innovative applications of the new VR, like experiments with lucid dreaming. Virtual and Augmented Reality have become ubiquitous, but the most interesting advances seem to be in the hybridisation of various technologies, which I am calling here “distributed” virtuality. After seeing Jill Scott’s Eskin4 at ISEA 2018 in Durban, I asked her what she thought of the VR revival.

“I do think VR headsets have immersive potential and also problems for particular themes like mine. I first worked with them a long time ago. In Interskin (1996), produced at the ZKM Center for Art and Technology, Karlsruhe, I used them to allow audiences to pick and choose 3D animated objects about health issues. But now I really prefer augmented reality (AR) because I am not that interested in escaping from this world but in overlaying audiovisual information onto it in real‑time. This is a technology which can provide the participants with a 3D-enhanced perception of a physical environment, but it is also capable of hiding or replacing real structures. AR fits with my focus on information that can reflect our social and environmental concerns about the real world. In my opinion this requires the mix of ambient and augmented reality and becomes more interesting with the addition of tangible interfaces.”[1]

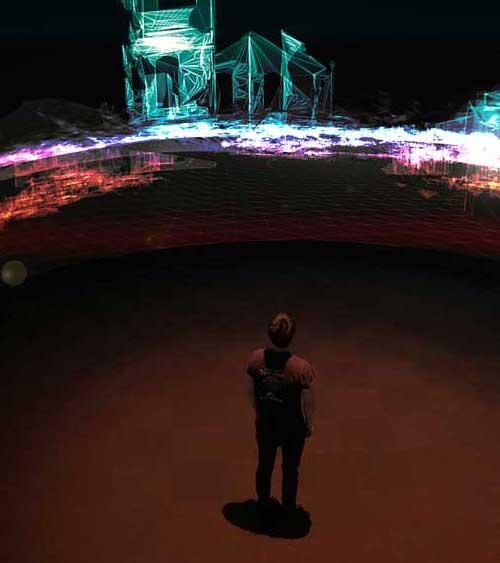

Eskin4 is a good example of a distributed version of VR. Working with visually impaired dancers from the Mason Lincoln School in Umlazi, Durban, Scott and her team wove together an evocative mixture of wearables, augmented reality, dance and movement-detected devices. It emerged from early experiments Scott conducted with electronic skin (or e-skin) in neuroscience labs in Zurich.

Scott recalls: “We originally started this interdisciplinary research art project in 2003, with the Artificial Intelligence Lab and called it e‑skin. Then the aim was for media artists, neuroscientists and artificial intelligence researchers to work together as a team on an electronic interface that bio‑mimicked the behaviour of human skin. By 2007 we had constructed an interface based on an embroidered circuit that mimicked temperature; pressure and vibration with electronics to help visually impaired people with their navigation and orientation problems.”

Scott’s recent interspecies work Jellyeyes (2016) also reflected this orientation approach. Presented as part of Femel Fissions: Women, Art & Science at the Queensland University of Technology for Science Week and at the Zoologisches Museum in Basel, this worked with the simulation of jellyfish, human and squid vision, “combining aspects of neuroscience into a creative ecological approach. In Jellyeyes the viewer stands inside a semi‑circular photograph of the Barrier Reef holding a tethered iPad with which the viewer can connect words, images, films and sounds to reflect upon the evolution of vision and how it is related to symbiosis, movement, survival and our fragile environment due to the warming of the oceans ... For example, in one part the viewer can “see through” the eyes of a box jellyfish or a giant squid and these interactions raise awareness about our role as humans in the future of existence.”

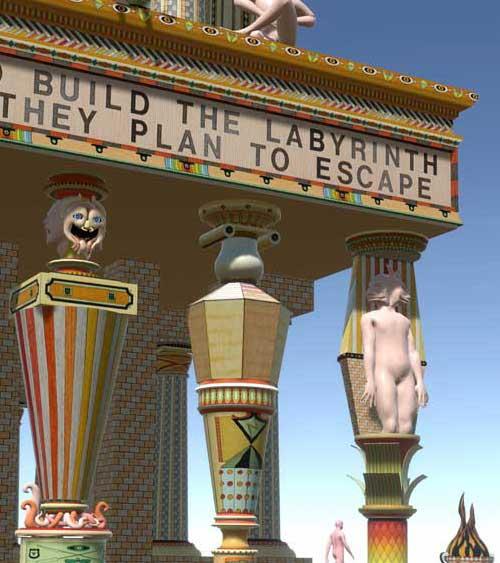

In the 1990s many artists were excited by William Gibson’s Neuromancer and the concept of “jacking in” direct human brain‑computer interfaces. Nowadays we have the horrific notion of drone pilots going to work in the morning, spending all day in a virtual killing environment remotely, then returning home as if nothing had happened. If the military found a way to really “jack in”, future wars would be between minds. Some now see the weaponisation of the internet and gaming as the start of this process. Michael Heim foresaw some of the worst elements of this in Virtual Realism, describing Alternate World Sickness (AWS) “as technology sickness, a lag between the natural and artificial environments. The lag exposes an ontological rift where the felt world swings out of kilter. Experienced users become accustomed to hopping over the rift.”[2] Citing a scientist who uses VR extensively “his work in VR often has him gesturing in the primary world in ways that function in the virtual world. He points a finger expecting to fly … His biobody needs to re‑calibrate to the primary world.”[3]

Scott’s career has taken her from the early days of virtual reality to a time when the technology seems to be making a comeback. What was her opinion of all this? She agrees that virtuality can provide dystopic results: “I remember being horrified when I saw Anne Hathaway give a disturbing performance in New York as a drone pilot in a play (Grounded by director Julie Taymor) about the effects of killing by remote control. It’s the role of media artists to be critical. We need some deep thought about this kind of “mind out of place” experience in VR and the effects of it on the developing brain and neocortex. I know some neuroscientists like Susan Greenfield are really worried about the subversive effects of VR gaming. I would suggest a more augmented approach, and one that is critical of the disturbing effect of seeing ourselves elsewhere than expected, and often even reflected back to ourselves inaccurately. I was always wary of Second Life avatars for these reasons. Media artists in particular can take more responsibility … Even in William Gibson’s concept of “jacking in” the major ethical issue is the substitution of VR immersion to deal with this planet and its problems. All the time you are reading his novel, you are thinking how did we get the economy and its employees to this point? Unfortunately, we are getting close to the same scenario of a few corporations ruling the world and if you are not a jacked‑in online member then your role might only be as an outcast or a rebel.”

Despite these dystopias, Minna Långström has made a work about the positive elements of human‑machine interaction in her film The Other Side of Mars (Napafilms, 2018). In this she explores the life of Vandi Verma, a Mars rover driver who daily works with the Curiosity rover on the surface of Mars. It’s clear from the film that through her virtual life on Mars she begins to extend her identification with the rover, casually mentioning that “we” landed on Mars. In an interview, she expands: “if you work on multiple robots … they’re in different environments. They’ve had different sets of paths that they’ve taken on Mars … and done different things that either fail or degrade, and that gives them a personality, for the lack of a better word.” Vandi more‑or‑less lives through the robot. Her life away from the rover is like the reverse of Heim’s AWS: “It’s true that when you work on Mars you are limited … you can’t just turn your head around and view this missing gap. If it’s not there it’s data that’s missing.” Interestingly, none of the successfully landed Mars rovers has ever been fitted with a microphone, so we have never heard the sound of the wind on Mars, or even the noise of Curiosity as it digs for samples. That might enhance Verma’s daily virtual experience.

In contrast, Scott’s Eskin4 was developed with learners that also have limitations in their field of vision: “We had to work differently than with sighted participants. The choreographers could not say ‘watch me!’ which was unusual for them. On top of this, they had to learn how to ‘play’ the interfaces … We had to limit the stage light on the participants’ faces as it disturbed the few that could see some light. But they learnt fast … We placed a tactile stage edge on the floor, so they knew where the stage began and ended … But in other ways their tactile and sound senses were much more developed … They all have developed a much higher frequency range in the audio perception and they have all learnt to use echo location for navigation. Also, their perceptive tactile identification of skin pressure, temperature and vibration is unbelievably accurate.”

Kathleen Rogers is another artist that has pioneered work with VR in the early 1990s. She agrees that the “distributed reality” approach is the way to go. “In the 90s I was using the basic VR kit to explore the psychological, phenomenological and aesthetic aspects of immersion and experimenting to find ways to new ways to make art, working with the enhanced and unsettling new agency of observation and movement VR provided … the technical set up at that time was primitive and non‑distributed.” She, like Michael Heim, saw wider possibilities for the use of virtual reality in consciousness research: “The dislocation of gravity and the sensory of bilocation of being simultaneously in two dimensions of space/time offered possibilities to imagine new kinds of performative extension and sensory reach. Her early work with helmet and glove included works like Hauntings (1993) and The Electronic Void (1994) and she went on to apply VR techniques with the late Professor Robert Morris from the Edinburgh University Department of Parapsychology, using Ganzfeld chambers to isolate subjects in telepathy experiments. This continued in the work Psi‑Net (1993), presented as part of EarthWire (1994) curated by myself and Tracey Warr, working with spirit mediums in ambient virtual environments. Along with Heim, Rogers took part in The Incident for the Belluard‑Bollwerk Festival in Fribourg and the ICA in London in 1994–5, co‑curated by myself and James Turrell, where she presented distributed ambient VR works including The Memory of Water (1995) and Viperscience (1996). Like Scott, Rogers was critical of the dystopic possibilities of “jacking in,” and in a prophetic article in Variant in 1992, “Virtual Real Estate,”[4] she anticipated military uses of VR, teledildonics, and even “biochemical VR,” something now possible with the emergence of synthetic biology.

The activist element in Eskin4 is that it has a purpose to extend awareness of climate change. As Scott says, “The learners were asked to list their experiences of sound and touch when they were children. They all come from the countryside and were asked to compare these memories with those of their parents. For them climate change can be felt and heard, rather than seen. For example, they all said that for them the ocean was a very calming experience, but their parents were worried about the disappearance of a favourite tactile experience in the form of the sand. They were all worried about the forest and believe that Mother Nature was a shape shifter and may run out of animals to shift into.” The distributed reality of that experience made this shape‑shifting almost real.

What’s next for Jill Scott’s virtual projects? “The next work is called Aftertaste, and it is based on the anatomy of the olfactory system and how flavour is based on the combination of taste and smell … based on the autonomy of sensory perception ... The content is based on research about the flavour, molecular behaviour and health benefits of roots like the chicory plant root (cichorium intybus). Here the public can learn about the specific molecular healing properties of roots, seeds and leaves in an engaging way. Due to climate change more resistant plants have to be re-introduced into our diet and these plants may also help to un‑monopolise the current lack of nutrition found in monocultural activity. Like Jellyeyes and Eskin4, Aftertaste attempts to bring neuroscience and ecology into the same room.” Responding to the lack of microphones on Mars, touch, taste and smell are the obvious next step in distributed VR across these ambitious projects.

Footnotes

- ^ All quoted discussion with Jill Scott, unless otherwise indicated, is from an interview with the author on 7 September 2018.

- ^ Michael Heim, Virtual Realism, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 53__3 Michael Heim, p. 54.

- ^ Michael Heim, p. 54.

- ^ Kathleen Roger, “Virtual Real Estate,” Variant, no. 11, Spring 1992.