The Riddoch Art Gallery’s inaugural International Limestone Coast Video Art Festival is a welcome addition to South Australia’s strong focus on film, digital and screen cultures. What’s not to love about the moving image, fast outpacing more traditional forms of the visual arts for its enabling pursuit of creative world-building. As the outcome of an open call and curated selection, Melentie Pandilovski (former director of the Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, and Videopool in Winnipeg) has a declared interest in this technological space, bringing to the program in Mount Gambier in the build-up to the festival notable presentations on VR and other digital and art–science agendas.

The opening weekend symposium on the theme of the “Video Body in the New Millenium” was led by Perry Bard on New York time discussing her take on the video body as license to cast herself in the role of mess-making avatar in The Kitchen Tapes, embracing performance as interventions into daily life, so central to first-generation video art. This and the concluding presentation by Luke Pellen on adventures in Rapid Game Design, modelled on speed dating, prompted a generational flip around the immediacies of activating new technology as a creative work space.

This idea of the flip, underscoring Melentie Pandilovski’s interest in applications of the technological image as a negotiation of innovation and obsolescence, takes on board Marshall McLuhan’s categorisation of the Laws of the Media and broader discussion around generative systems of image production and the embodied subject, in the process blurring the boundaries of image production made with or without the aid of a camera and across vastly different work spaces. In this regard, Julianne Pierce’s short history of where we are going with video and the technological space, most notably by the promises of VR, was usefully highlighted in some key examples of developments in software, such as the remarkable Osmose (1995) created in Softimage 3D by Char Davies.

As part of the seminar and workshop program, Vladimir Todorovic’s VR work Endless Nude Runner was presented as a work in progress responding to early photography of the body in motion and an art-historical obsession with the female nude descending the staircase inspired by the example of key works by Duchamp and Gerhard Richter. If somewhat awkward in the clearly gendered white body of the female mannequin, a problem the artist readily acknowledged, the intense negotiation of this poetic grey world of ambulatory space was mesmerising on its own terms, demonstrating this softer realm of linear and biological break-down in encounters with seen and unseen obstacles as the VR equivalent of what was once pure horror as alien mutation in John Carpenter’s The Thing.

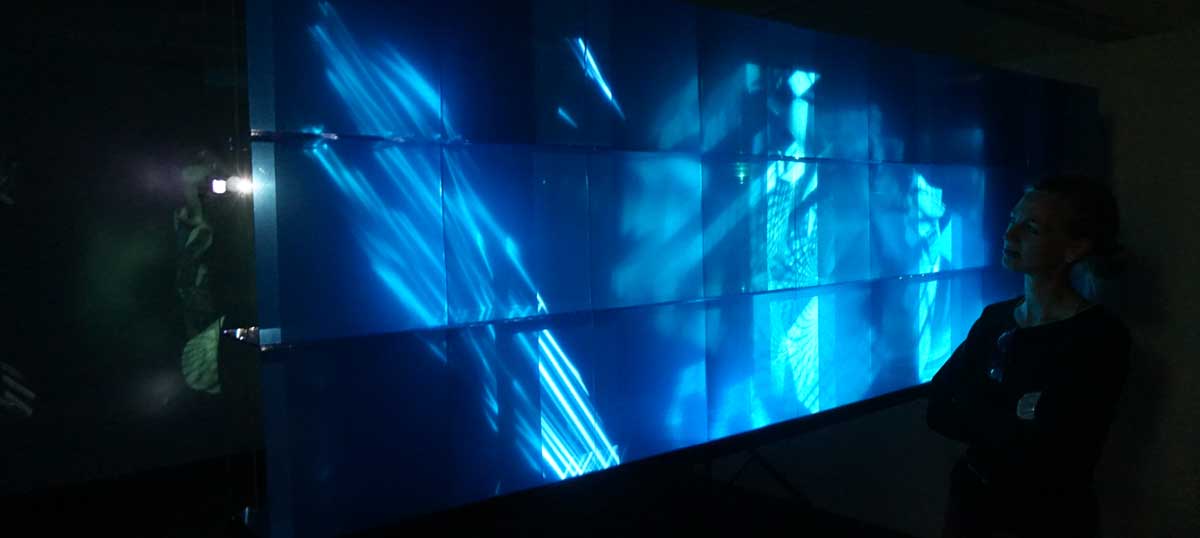

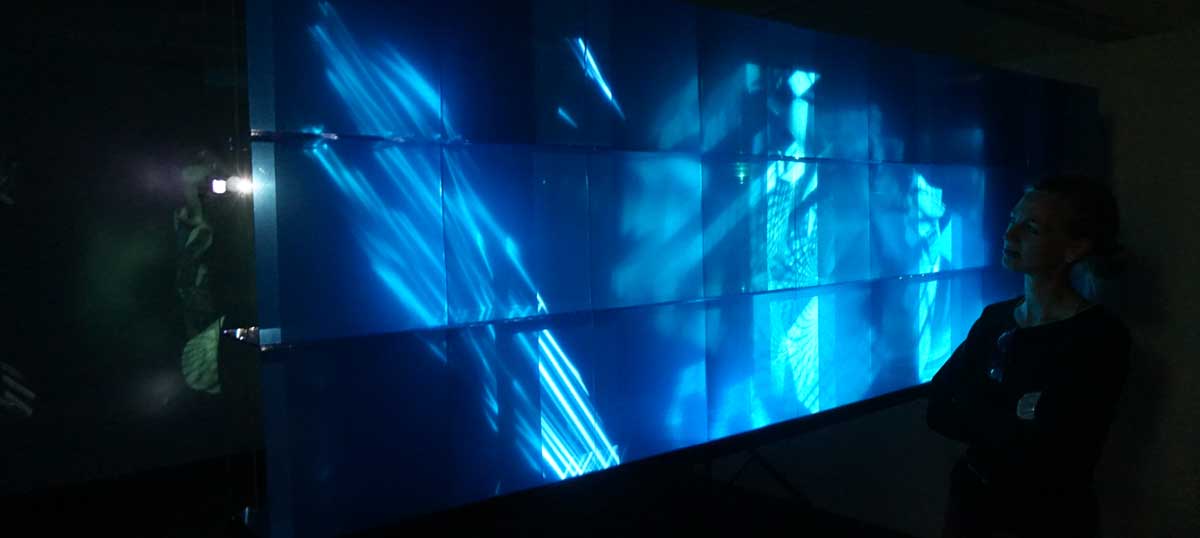

Messing with ideas of interactivity, and the advancement of technology, the video installation works on show used some visibly old hardware to embrace this theme of innovation and obsolescence. These included Ariel Hassan’s Traces and Determinants, a flickering sound and light projection work of grey bacilli-like animated forms representing the life cycle, displayed on pull-down screens like an old-school science lab, and Manuel Chantre’s Blur Rouge Carmin, an immersive and partially interactive work of multi-screen 3D stereoscopy responding to algorithmic samples of the spatial dislocation of social media, while also phenomenologically resembling meditations on urban transport in the built environment. But perhaps the work that best summed up this technological blue flower as metaphor for transience and decay was the mischievous Fallible by Raewyn Turner and Brian Harris. A video work with an accompanying live demonstration of a robotically enhanced rotating bouquet fuelled by the off-gassing of its own expiring blooms, this is practical magic in an everyday setting inspired by the trickery of a camera angle.

The program of videos selected for exhibition were all relatively short and boldly intersectional, representing diversely positioned narratives and takes on a theme. The selection panel (including media theorist Ross Gibson, producer Julianne Pierce and local artist Melissa Horton) clearly had their eyes on the prize in choosing incisive, aesthetically adventurous, singular works that variously embraced the economy of a medium that thrives on experimentation, performative role play and point of view. One section included all women’s work included stop-motion work, with animations enshrining the body in movement, such as the shape-shifting image of the body in Whale by Margit Bruenner and My Flesh Crawls by Alison Davis, with its beautifully raw and inflected skin tones, and local artist Caroline Hammat’s fluidly overlaid self-portrait, Identity. Dissassembling and reclaiming ritual images and traditions of the image is a great part of the feminist film work, and here included Nasim Nasir’s, Worrybeads 2 and Vigilance by Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Milan, decrying screen violence against women in a remarkable work of remastered film as scratch video, as well as Deborah Kelly’s grand gestural sweep of art history with her potpourrie of nudes in Lying Women, freeing Venus in all her vast mutant reprographic shades from the pages of published art history.

Media work as a visual membrane of motion, transport, passage, resistance and the visualisation of neurological and biological networks provided a further strong thematic to this focus on the social and physical body. These included Anne-Marie Bouchard’s Don’t Give an Inch, another remarkable work of scratch compilation video visualising the motivated point of view of children as figures of resistance, and Self Love by Emily Helps and M. J. Seymour, as an inspired action against the hate culture of bullying in schools, that won the festival’s youth award. A strong component of digital art is world-building and this challenging articulation of new futures underscored the overall winner of the open call component of the program, Static Glow by Ryan Cherewaty, a superhuman dance in a future where humans live alongside robots and Artificial Intelligence. I also enjoyed wandering through the psychedelic forest of the microbial world in Mycolonguistics by Ash Coates and Fiddling Neurons by Lesley Naokonechy, a compelling and thoughtfully scripted narrative about a family member’s slow submission to Alzheimers.

As a visitor to the region, it is hard not to bypass the topographical element of Mount Gambier’s extraordinary geological history and unique landscape of craters, caves and sinkholes (the “Limestone Coast” part of the Festival’s geographically specific identity) and seeing some part of the inventive capacity for visualising new landscapes as an embodied vision. The focus on the environment is also underscored by a clearly global cause to document and evaluate our natural and human heritage. Expeditions and interventions in the landscape as performative encounters provided another strong thematic focus in the works selected for the exhibition and awards, including C.J. Taylor’s The Hut, Dominique Rey’s Funambule and Caroline Monnet’s Mobilize.

Creation myths and critiques were the focus of works such as Rick Fisher and Don Rice’s Arcadia and the particularly compelling performance work Founder by Canadian Leah Decter and Cheryl L’Hirondelle, undoing European settler claims on the land and waterways. This brings me to the main criticism of this otherwise remarkably compelling program of video work in the clear imbalance between international (mainly North American) and Australian content. The remarkable absence of works by some of our leading and emerging Indigenous media artists is clearly an omission. But I believe, from talking to festival organisers that they are already on the case to ensure that the next iteration of the International Limestone Coast Video Art Festival is more representative of the rich diversity of practices from Australia and the Asia-Pacific.