.jpg)

Living in a time of the greatest mass migration of displaced people the world has ever known, this issue responds to ideas of human flow, trade and transit in the information age, and the role of artists as social agents, antagonists and radicants. Ideas of radical, impactful or dissident art differ widely, but perhaps no other artist is so observable in the media for his championing of human rights as Ai Weiwei, whose Law of the Journey (2017) is reproduced on the cover of this issue. Occupying almost the entire length of the former turbine hall at Cockatoo Island, this 60‑metre‑long rubber life raft, stuffed with over 300 replicant humans made of the same material, was a destination piece for the 2018 Biennale of Sydney.

Only the second time the work has been shown, the Australian presentation pointedly shared a similar distinction to that of its exhibition at the National Gallery of Prague in 2017 at a time when the refusal of the government of the Czech Republic to accept refugees was at odds with most others in Europe. Some eighteen months later, this position may not seem so radical. As stand‑ins for an accruing world statistic of border control and contravention of the once inalienable rights of asylum, these faceless figures mirror the void of Australia’s own bureaucratic minefield of maintaining a policy of mandatory offshore detention and relocation through applying the full letter of the law to a relatively small number of individuals that might just as easily have been absorbed into our daily population intake coming in by plane.

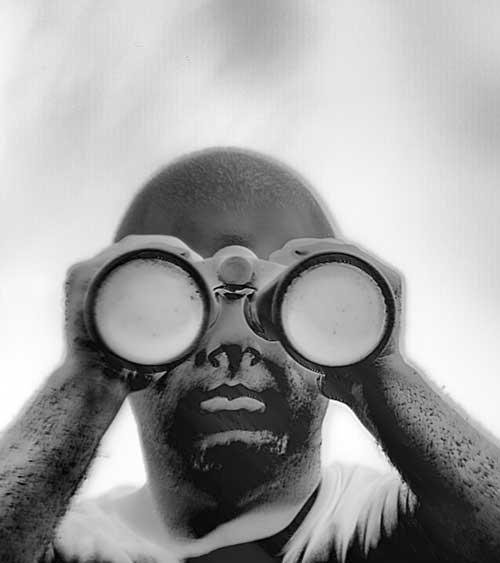

The metaphor of the boat arrival looms large in terms of Australia’s origins and defences. Monumental, if not over‑stated—Ai Weiwei is not renowned for being subtle—Law of the Journey and the accompanying wall of photographs and film works, culminating in the documentary feature Human Flow (2017) takes us on a journey across the world to survey the present humanitarian and refugee crisis from the point of view of the artist as empathic observer. From the earliest scenes of the unfolding crisis that Ai experienced by visiting the shores of Greece in 2015, to the broadening scope of his documentation working with a team of filmmakers and producers in various locations, we are presented with affecting face‑to‑face scenes and wide‑angle views that capture both the intimacy and immensity of the experience.

.jpg)

This “sublime plight” as described by Wes Hill in his opening feature, is not without its detractors. Hill’s response to the work of Ai Weiwei and Richard Mosse’s Incoming (2014–17), on exhibition as part of the NGV Triennial, embeds the crisis in the very act of representation and the pitfalls of spectacularisation for pure affect: “This is the dilemma of politically motivated, pathos‑laden work: how do we negatively judge something that has such a good heart?” Or, put another way, how do we put the ethics back into the aesthetics?

Driving the momentum further to embrace the complexity of experience and the strategies of representation that get us there, the practices surveyed across these pages pitched around ideas of human flow and agency address a range of topical concerns. This includes Sasha Grbich, writing on Xu Bing’s Dragonfly Eyes (2017), an epic narrative of life, death and surveillance entirely composed from found camera footage, contextualising the dilemma of violence against women.

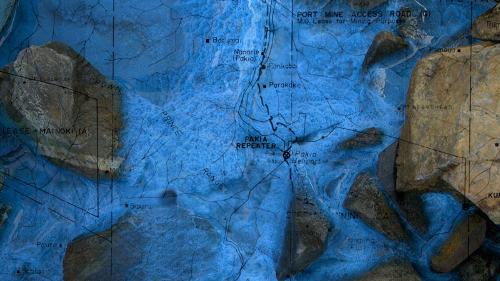

Nicholas Thomas, co-curator of the forthcoming exhibition Oceania at the Royal Academy and Musée du quai Branly, looks to developments in recent art from Melanesia, with a focus on the evolving series of artefacts and habitats of Taloi Havini. Habitat, the film work, awaiting its next iteration for APT9 at QAGOMA, is a mesmerising portrayal of the residual impact of copper-mining on the landscape of Bougainville, documenting its people and environmental flows.

.jpg)

Cultural producers are primed to come up with subtle and pointed ways to express dissent. Alana Hunt’s Cups of nun chai was just the starting point for an interview with the writer, photographer and filmmaker Sanjay Kak, in a conversation about Kashmir. For artists working in China, dissenting views are even more likely to be at risk of censorship. In a frank and fascinating overview of recent art from China, Darren Jorgensen and Tami Xiang survey the work of artists working within and in contravention of the rules of state-sanctioned guidelines for public exhibitions. The dilemma for those working between cultures and within the global context of contemporary art is how to survive in both worlds.

For the Tiananmen Square generation, many of whom relocated to Australia and other countries before returning to China, the life of the “foreign returned” is also a defining one. Introducing the term to this issue, Baloman Shingade recounts his experience of revisiting Mumbai to frame a discussion around the practices of the South Asian diaspora in Beyond Transnationalism: The Legacy of Post Independent Art from South Asia at the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum. And, in a further account of practice that absorbs the complex inter‑generational experiences of war, migration and displacement, Ian McLean’s extraordinary review of Imants Tillers: Journey to Nowhere at the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga further problematises what it means to grapple with identity in a trans- or post-national world.

Going beyond the goal of safe harbour, across the various artists and projects profiled in this issue responding to the ideas of human flow it is the fluidity and depth of good will and thinking that sustains the momentum.