As we drove out to visit Raquel Ormella’s survey exhibition at the Shepparton Art Museum, I recalled to my companion the strangely pleasant anxiety I had experienced when installing Ormella’s Australia Rising #2 (2009) at the National Gallery of Australia, not long after it was acquired. With its limply draped ribbons stitched into four and a half metres of patchworked and distressed Australian flag ephemera, heralded by the slogan CORE PROMISES across the centre, the work had the appearance of both dishevelled political propaganda and DIY protest sign. It was five years after the Cronulla riots and the Southern Cross was now firmly tattooed into the white shoulder of nationalism. The Australian flag was increasingly contested as a national symbol for its associations with genocide and constitutional exclusion. It was also a time impacted by an awakening political doublespeak – in which the Australian electorate was being asked to make distinctions between core and non-core promises – and an increasingly neoliberal agenda was being promoted in approaches to freedom of speech, as in freedom to express racist beliefs. I did wonder how visitors to the nation’s capital would respond to Ormella’s textile interventions. Would they get it?

With a similar bravado, this exhibition on the commencement of a regional tour, goads viewers: “I hope you get this,” as the title of the exhibition curated by SAM Director Rebecca Coates and Senior Curator Anna Briers asserts, is playing on the persistent insecurities of addressing publics (for artists, curators and politicians alike). I took this challenge to heart as I moved through the exhibition’s six rooms reading the exhibition texts, and taking my time to absorb the many narratives and formal interventions, while also eavesdropping on other visitors’ conversations. By contrast, my companion making a quick loop of the show before I had even got through the second room, calmly summed it up: “I get this. It’s funny, political and original.” This apparently unintentional response to the title is an astute reflection on what this show achieves with a thematic rather than chronological approach to grasping Ormella’s conceptual and material concerns. Comprised of mainly recent works, with some key examples from the last twenty years, this exhibition brings together the largest selection of Ormella’s textile works to date. But this physical threading can be conceived as a mere by-product of her activist aesthetics as an ongoing engagement with environmental and other social issues. The personal is political and poetic, as expressed through the use of everyday found materials, much of it sourced second hand.

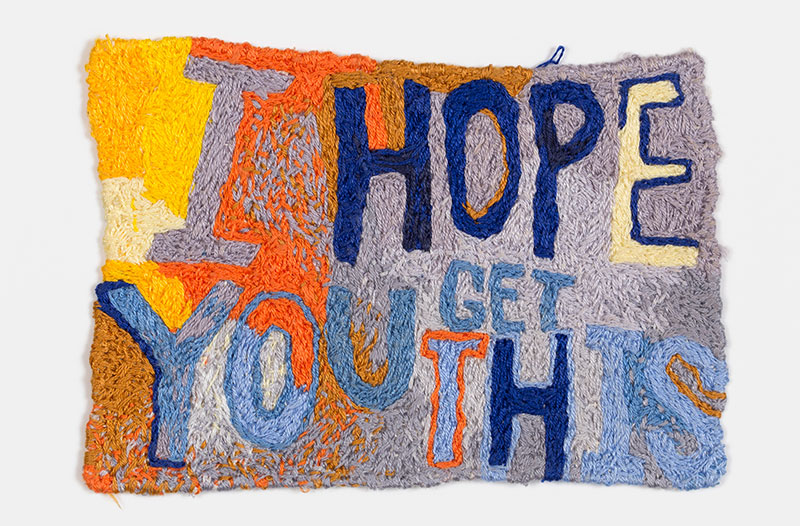

The phrase “I hope you get this” is drawn from one of the tiny new hand-embroideries Ormella has been making while travelling around the country, most notably en route between Canberra and Shepparton in preparation for this exhibition. Collectively titled All These Small Intensities (2017–18), the work is comprised primarily from the threads of previous unrealised projects, and materials that have been collected or gifted to the artist over decades. As the first body of work encountered in the SAM show, All These Small Intensities acts as an introduction to an artist who gleans widely from her surroundings and considers her place in the world as a maker. These intuitively developed embroideries are part of an evolving body of work that appear like notes to self or an offbeat contemporary iteration of the traditional cross-stitch sampler, with affirmations like LET IT GO and tributes such as MY FATHER’S WORK CLOTHES. Displayed on acrylic sandwich boards hinged to a reverie-inducing soft pink wall, they work like archival fragments mined from personal archaeologies.

This initial installation sets a tone for the first series of rooms in the exhibition as an archive of environmental and social concerns. The re-purposing of SAM’s large floor-to-ceiling glass showcase for the installation Bird Hunter (2004–18) is one of the most substantial examples of this archivist approach to exhibiting. Here, Ormella’s “twitching” inspired videos accompanied in the display by bird-themed ephemera, also include a focused celebration of ceramics drawn from the SAM collection. Displayed alongside a new installation work, City of Crows (2017–18), these two rooms illustrate Ormella’s interest in avian populations, included as a kind of bellwether for other species, environmental health and threats to the natural order.

This body of work leads into the major series of whiteboard drawings, Wild Rivers: Cairns, Brisbane, Sydney (2008), that forms the conceptual and aesthetic groundwork for Ormella’s approach to environmental activism. Here, her exquisite marker illustrations of office interiors, campaign material and other images accumulated while embedded in The Wilderness Society from 2005 to 2008 are a record of the intimate spaces and organisational grass roots of activism at its source. When first exhibited as part of the 2008 Biennale of Sydney, viewers could walk around the portable boards, and could even print off and take away a copy of the illustrated record, doubling the functionality of this office-resourcing. Like the campaigns referred to, the curator’s wall text recognises the archival nature of the Wild Rivers boards as “monuments to past successes of grass roots campaigns.” Similarly, Reuben Keehan in his catalogue essay, takes a nuanced view of the losses incurred by this time-specific work almost a decade after its production, following the repeal of the Wild Rivers Act and the obsolescence of the technology itself. SAM’s protective museum barriers, erected to prevent curious fingers getting close enough to test the permanency of the marker, imposed a further limitation and hindrance to walking around and viewing the work up close. Anotheranalogue relic for the archive, this work has itself become a monument to obsolescence.

.jpg)

Moving into the comparatively uninhibited display space of the banner and flag-based works re-engaged the momentum and felt like an encounter with the beating heart of the show. Here, the “decay aesthetic” is in full swing but freed from the torpor of the archive. The curators have made a strong selection of works that harness the currency of concerns about the Australian flag, a revived and questionable nationalism, and the whitewashing of our national history. As the didactics make clear: “While many fight proudly to uphold the Australian flag and all that it embodies, for many Aboriginal people it speaks to their dispossession as Australia’s First Nation’s people.” In the work titled Return to the Beginning (2013), for example, Ormella has cut away at two Australian flags to reveal in one flag this same text, and in the other a blank space with only the outer seams supporting a new arrangement of stars falling below the textile frame, each of which have been textured with small burnt holes. The “air of protest and poetry,” as discussed by Kyla McFarlane in her catalogue essay, is captured in the incendiary spirit of the burn holes that are Ormella’s mark of choice to trigger new national imaginings from this “existential blank slate.”

Continuing on this theme, in what McFarlane describes as Ormella’s “hubristic assertions,” Wealth For Toil #1 (2014) adds to the possibilities the wreckage of GOLDEN PROMISES. McFarlane describes the work as performing “a beautiful entropy with the lower half of the work unravelling … its promises and the foundations on which they are constructed, break[ing] apart thread by thread.” With its title drawn from our national anthem’s reference to natural resource abundance and contemporary labour values, it is paired with a more recent work, Wealth For Toil #5 (2017–18). Constructed from hessian and charcoal, in reference to SACK CLOTH [and] ASHES, this version replicates the shame of the Biblical “sack cloth” in an allusion to Australia reneging on international targets for reducing reliance on fossil fuels, in particular coal power. In other banners Ormella’s bricolage of King Gee and high-visibility workwear continues the reference to labour, and the social impacts of the fly-in-fly-out culture of the mining industry’s mobile workforce, as well as the overriding principle of the land grab behind the exploitation and desecrations of natural resources and traditional lands.

Courtesy Milani Gallery, Brisbane © the artist

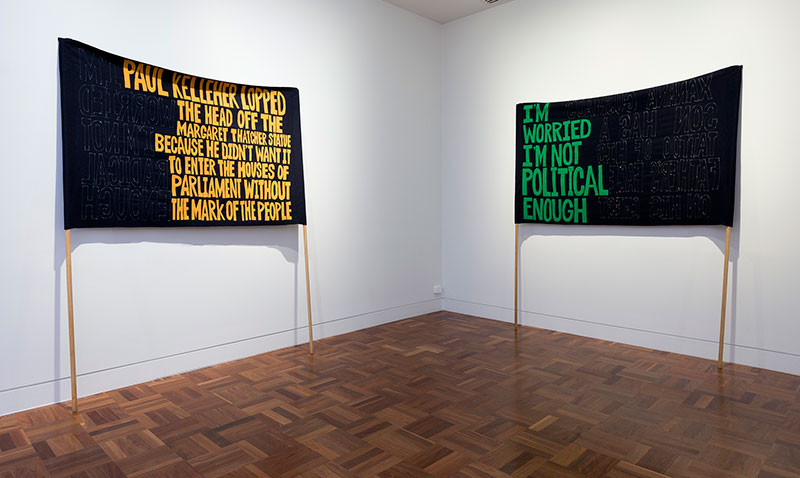

Drawing on the rich cultural and material histories of quilting and “making do,” intrinsic to European settler cultures, Ormella’s protest paraphernalia is rich and layered with historical references. It also sums up the anxiety surrounding socially engaged practices today in two banners in the final room belonging to the well-known series I’m Worried This Will Become a Slogan (1999–2009). With their combination of self-conscious and boldly political language – and a material nod to Joseph Beuys – these never-to-be-marched protest banners tie up this survey with a well-aimed parting gesture of apparent self-censure and doubt around the possibility of communication.