.jpg)

Decolonising is a verb that explains the act of “purging” or liberation from colonisation; the freeing of the dependence of one country on another. The very notion of decolonisation in its strictest sense implies the sovereignty of the colonised nation, and embedded within this is the agency implicit in being sovereign, or standing alone. Indigenous decolonisation as it’s referred to throughout this issue is the contemporary process by which First Nations peoples whose communities were grossly, unequivocally affected by colonial expansion, genocide and cultural assimilation, reframe their own structures of thought, understand the history of their colonisation and reinvigorate tradition, language and cultural values and the simultaneous consideration of a new way of walking through the world. Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community will, inevitably, approach the idea of decolonisation in a multitude of ways, as diverse as the number of languages spoken across the continent.

It is with this consideration that I acknowledge that the decolonisation of self is critical to the overall process of freeing oneself from postcolonial trauma, and with this in mind it is important to introduce myself. I am a proud Wardandi/Badimaya woman with French/English heritage. I am a mother, aunt, daughter, granddaughter and cousin. For the last fifteen years I have been a curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, situated currently within a non‑government organisation. I sit in a third space of cultural hybridity that has asked me to become proficient at code‑switching, and as I don’t live on my own home country in the southwest of Western Australia, but on the lands of Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, I am critically self‑aware of when it is my place to speak, and not to speak.

This contemplation of the protocols around speaking and the importance of language, supported by the two language titles for this edition, is also critical to the ideas framed in the commissioned essays, artist and project profiles. Co-editing this issue with South Australian Nunga Kaurna artist James Tylor, we felt it was important to decolonise the titling of this issue with dual Aboriginal titles from Nyoongar and Nunga languages. Broadly, in the predominant Aboriginal language of the southwest of Western Australia—often described as Nyoongar (although this in literality means “man”)—Kanarn Wangkiny means speaking authentically or speaking the truth. In the Nunga language of the Kaurna people from the Adelaide plains in the South East of South Australia Wanggandi Karlto means speaking from the inside, or to speak from the heart.

James and I were struck with the similarity of our languages and their contextual meanings, although given the proximity of our language groups it shouldn’t be so surprising. Both of our languages belong to the Pama–Nyungan languages family that stretched across the continent of Australia. Pama–Nyungan languages is a unique family of human language that is bound together by thousands of years of diplomatic trade and cultural relationships through cultural songlines and trade routes across the Australian continent, not unlike the union of European languages as Latin and Germanic languages that spread across Europe and then the rest of the world through war and colonialism.

The very real act of our ancestors moving through each other’s country, trading with one another and potentially sharing their lives in some ways was brought very much into the present in the way our languages could be similarly decoded. The act of sharing language, of facilitating access to each other’s semiotic inspired and moved us, and also supported us in the need to shed more of the coloniser’s skin and communicate directly to one another. We acknowledge this issue is in the English language—and the importance of the reclamation of language is a topic too large to address fully in this issue. But it is important that our contributors were able to speak authentically and stand in their own truths while speaking in the language of the coloniser.

The work on the cover of this issue, from the series sovereignGODDESSnotdomestic by Mirning artist Ali Gumillya Baker, shown in the fierce and necessary exhibition Next Matriarch at ACE Open as part of TARNANTHI, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts festival across South Australia, is a call to colonised black women everywhere to reclaim their sovereignty, and their rage to dismantle the products of nationalism through imagining a Black matriarchal space going forward. It expresses the internal strength implicit within our cultures and visualises a world that consciously and collectively embraces its First Peoples.

Curator and artist Paola Balla, who is of Wemba‑Wemba, Gunditjmara, Italian and Chinese descent, also writes about the matriarchal performative practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as a documented way of surviving colonial trauma to supplement the colonial archive largely consisting of accounts by white men. Balla references “acts of disruption to white dominated public discourse” and that this can be employed in a variety of meaningful ways, including the use of ancestral language. This notion of the “self speaking back” takes on particular significance as an act (particularly by women) of decolonisation.

Katie West, a Yindjibarndi artist from the Pilbara region in Western Australia, now living and working in Melbourne, narrates the journey she is undertaking to address the decolonisation of self. Katie asks us to consider how we fit into the ecology of this landscape, and why do we continue to ask it to fit us. What does the country look, feel and smell like? Her intuitive practice gently revitalises traditional materials and ways of making, working in collaboration with, rather than against the land.

Ideas around environmental sustainability are also central to the essay by Emily McDaniel, a member of the Kalari clan of the Wiradjuri nation, who explains the curatorial thinking behind Four Thousand Fish, staged for the 2018 Sydney Festival. Conceived as a tribute to Barangaroo and the women of the Eora clan, it documents the concern for sustainable consumption and the clash between the attitudes of the white settlers in whose society the status of women was also seen as secondary to their male counterparts, unlike the position the Eora fisherwomen occupied as providers. This extraordinary project is also an act of physical memorialisation, feeding into the decolonisation process.

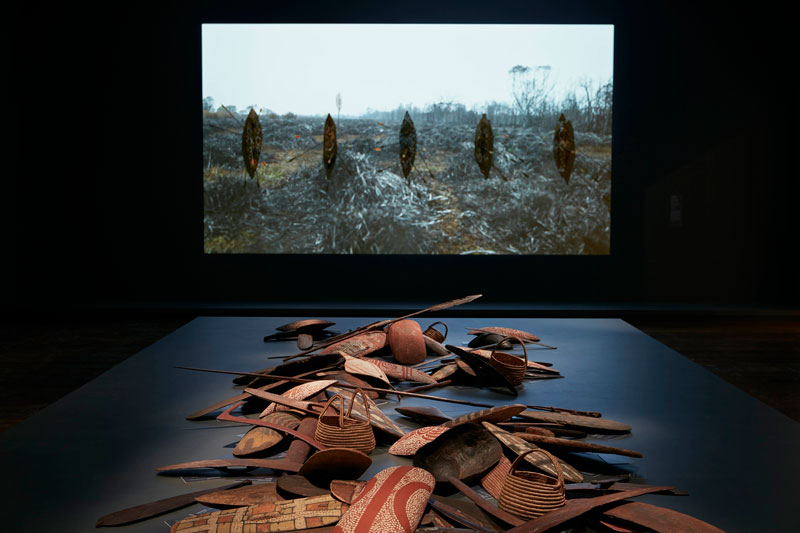

A performative approach to the museum object is also discussed in Marie Falcinella’s thoughtful profile on the practice of Narungga artist Brad Darkson, whose practice explores the use of ritual objects, divorced from their original cultural context in museum spaces to reconsider their signification and value. In a similar approach, responding to the more utilitarian objects and spaces of daily life, Kamileroi artist Archie Moore relates in the third person a powerful story of remembering the places of inhabitation to reconstitute a memento mori of the self. The sense of activation required to immerse oneself in Moore’s “rooms of memory” requires a visceral connection to the living memories of time, place and events as a record of the “daze of our lives.” Despite the title, Moore’s is an active, rather than a passive act of remembrance to further enact a decolonisation of the self.

.jpg)

From the physical to the digital realm, Susie Anderson in her timely piece on the use of virtual reality technology and web-based platforms by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, supports an enhanced social engagement and political resistance, providing agency and empowerment. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are ahead of the game in the connective agency of digital technology; our strength has always lain in our ability to effectively negotiate multiple and diverse relationships, within and across cultures. The blackfella grapevine is highly effective in sourcing and distributing information across all forms of social media and technology networks. Anderson outlines the five principles of Indigenous Digital Excellence, including the principles that digital participation must include the recognition of the sciences and knowledge systems of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the importance of cultural safety.

Cultural safety as an objective is addressed in many of the contributions to this issue. Paola Balla speaks about the need to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff in institutional settings that remain part of a hierarchical system, dominated by inherited institutional and individual behaviours. We can provide cultural safety through the acknowledgment of ongoing cultural competencies across our diverse histories as an engagement with language, in which Aboriginal people can speak confidently and authentically, without fear of reprisal.

The art of conversation is a powerful tool in generating safe and respectful spaces, as Coby Edgar, interviewing Warren Roberts, CEO of YARN, acknowledges in opening up the need for conversation to enable all Australians to consider Indigenous perspectives. More specific to the arts, we create cultural safety by acknowledging that art is not a commodity first and foremost but a vehicle for social justice, for activism, for resistance, for healing through cultural continuity and creation. We create cultural safety when we deliberately address sustainable mechanisms for employment and succession planning, because there is strength in greater numbers. We create cultural safety when we recognise that we do not belong on the fringes. We are at the centre of our own cultural universe. When we speak from the centre, from the middle, we have clear agency and integrity.

Kanarn wangkiny, wanggandi karlto.

Myles Russell‑Cook, Curator of Indigenous Art at the National Gallery of Victoria, writing on the NGV’s exhibition Colony: Frontier Wars, recognises the fact that no exhibition can heal the wounds of the past but suggests that it can open up a dialogue between the colonised and those who continue to benefit from colonisation. Russell‑Cook cites one important Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural protocol—that of community consultation as fundamental to decolonising curatorial and institutional spaces. I would go further to suggest that timely and appropriate community consultation should be structurally embedded in the governance of all cultural institutions and beyond.

Matt Poll, curator of Indigenous collections at the Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, in his overview essay on museology, also makes mention of the critical need for ongoing community consultation through an analysis of Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters at the National Museum of Australia, Gadi at the Australian Museum and Jonathan Jones’s barrangal dyara (a Kaldor Public Art Project) to explore the changing expectations of engagement. Poll’s coverage highlights the raft of recent museological inroads into celebrating and integrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander interventions into the imaginary landscape of white Australia.

In writing about his work on a master plan for Macquarie Point near Hobart, that will acknowledge the Black War as part of the built landscape, Lehman acknowledges the role that institutions can play in negotiating the fraught history of the nation’s relationship with its First Peoples. The complicity of museums in reiterating discursive structures that inherently, and at times automatically re‑colonise First Nations peoples is thoughtfully discussed, considering the ways in which museums can address our histories and the impact of colonial violence on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

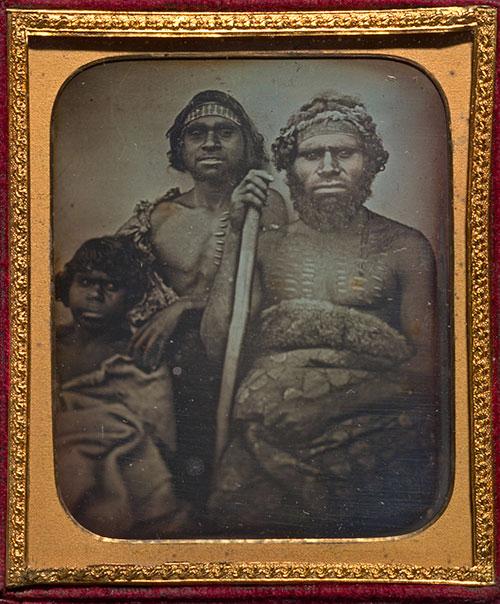

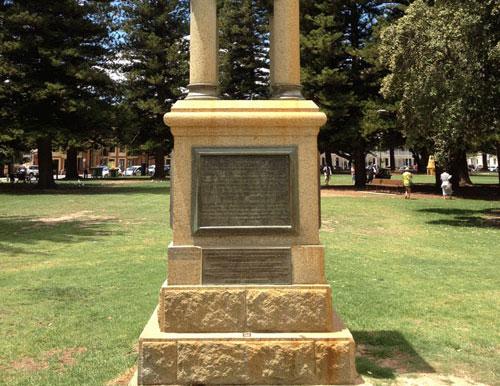

Civic spaces that can be activated artistically, culturally and socially as a dynamic approach to remembrance also preoccupy Stephen Gilchrist, Yamatji academic and author, writing on “dialogical memorialisation” in the context of public monuments, plaques and other singular historical narratives that white‑wash the past. Gilchrist suggests that local councils should routinely audit statues and plaques to update any ongoing narratives, given that culture is dynamic, not static, and there is ongoing research into histories of place. The democratisation of history requires that we as First Peoples create ways of memorialisation that place blackness in the centre and not merely at the fringes.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia are a walking politic, whether we like it or not, whether we engage with it or not. The very act of installing in the middle of a public square in the centre of Boorloo (Perth) the spirit (or kaarn/wirin) of Nyoongar resistance, Yagan, is symbolic of the restoration of Nyoongar cultural values within a civic space, and can be seen as a defiant act of decolonisation. As Gilchrist writes, “… if thousands of people who walk through Yagan Square and the Perth Stadium notice something they never noticed before, it might start a conversation, a line of questioning, or a new awareness surrounding the memory of a place. These public works of art slowly embed themselves in our collective consciousness and contribute to remaking the world otherwise and to describe what could come and what could be.”

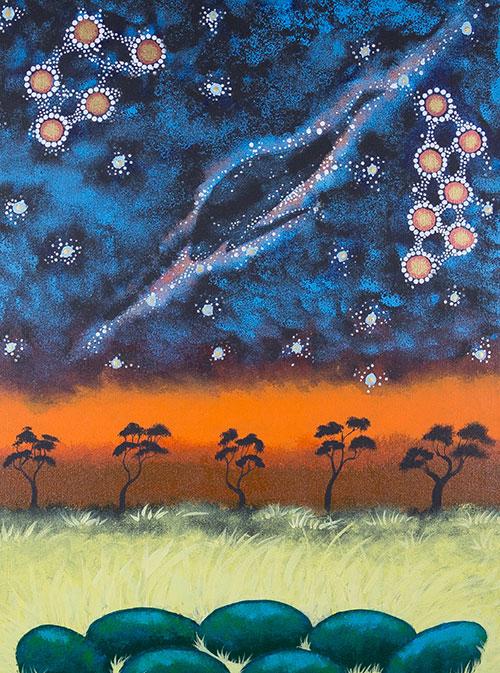

Creativity is also a means of contesting and reinforcing cultural values, as Charmaine Green writes in her poem “Sky World—Earth World—Art World,” it is about:

The power of reclaiming a space

The power of cultural knowledge

In a colonial contested community

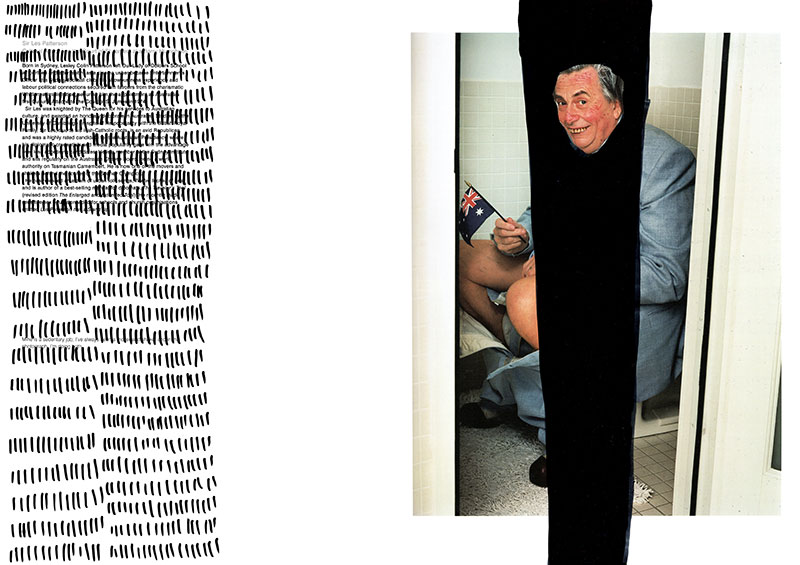

Equally, a work by Worimi artist Dean Cross—the image of Les Patterson scratched out with texta in PolyAustralis (2017)—is a compelling statement about the “white‑ing out” of Australia. These photographs, that have been extracted from a book titled “Australians,” which contains no images of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples. White nationalism and the complete absence of an Indigenous voice is dealt with by blacking‑out the faces of famous white Australians. Cross seeks to decolonise the thin veneer of Australia’s presentation of heterogeneousness and in doing so he asks the viewer to consider the implications of excluding First Peoples from this national space.

The Wadjuk Nyoongar weaver and maker Sharyn Egan creates large‑scale sculptural installations that gently reclaims colonised physical spaces that support being both an insider and an outsider. The inclusion of a large scale woven interactive work—Waabiny Mia—at the newly built Perth Stadium is an exploration of the ways in which built landscapes can be decolonised by introducing traditional techniques with new materials on custodial land. These ongoing interactions by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on their own lands links histories with materials, with time, and with language. What would it mean to have our language inscribed and embedded in every public area, on every institution’s website, on all exhibition signage? What would it mean to have cultural safety in our spaces, to be able to enact our curatorial or artistic practices with the knowledge that we will not meet resistance, that we will see change, and that we will be heard and acknowledged? This issue interrogates all of these propositions, giving voice to authentic and important speaking positions, giving generously of our spirits to yours.

Kanarn wangkiny, wanggandi karlto.

.jpg)