Louiseann King’s current exhibition arbor temporis momentum presents a compelling amalgam of early industrial, natural and domestic materials as still life, expanded to fill the historically resonant space of the Bendigo Art Gallery. Constructed as a series of seven individual works, arranged like islands in the darkened gallery, the works are presented on time-worn kitchen tables as their plinth or canvas, around which the viewer circumnavigates the resonant terrain. Shafts of light punctuate the space, setting a reflective and reverential tone. The lighting is an invitation to suspend disbelief the way we do in the cinema or the theatre, also for emotional affect.

Through what initially appear to be unassuming or even discarded objects – pre-modern scientific instruments, early-industrial glass and domestic fabric designs – King ponders the implications of this rich bric-a-brac. Natural forms, such as branches, leaves and deceased birds also occur among the tabletop arrangements, but turn out to be elaborately crafted bronze simulacra. The latter are achieved through the artist’s unique command of bronze casting processes, built over the last twenty years in collaboration with several well-known foundries in Melbourne. King writes that for her, the “translation from the natural to the artificial using specific manufacturing techniques, here jewellery casting, implies both a sense of preciousness … and an ominous feeling for a future where the natural will have to be manufactured.”[1]

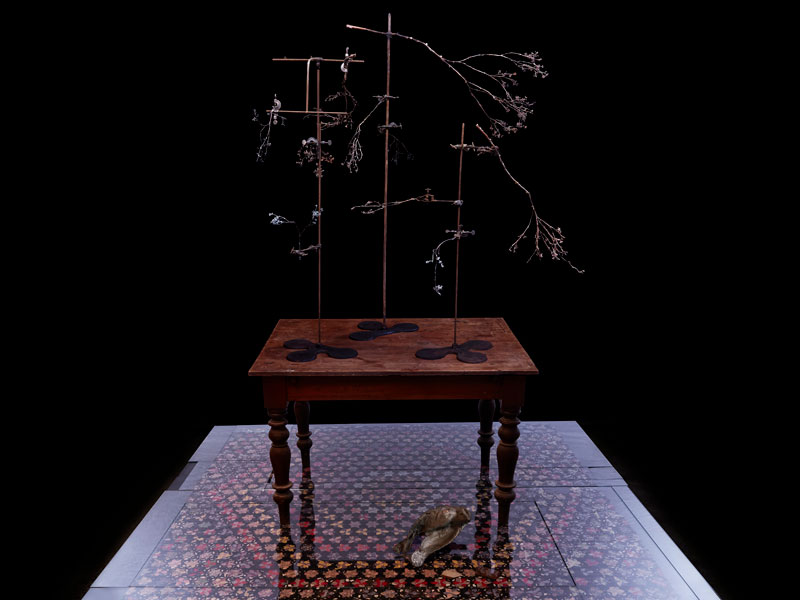

This philosophy can be seen clearly in the individual work, arbor temporis momentum – genere, where the artist arranges a spindly latticework of bronze-cast twigs that seem part of a tentative scientific experiment. A selection of near-impossibly delicate bronze branches with tiny buds are suspended from laboratory clamps in a bizarre parody of an actual tree. Strange clover-like forms support the construction, as if inviting illusive luck to bless the enquiry. The tree has entered the symbolic as the idea of a tree and it cultural representation (European), is symptomatic of its destruction and our appreciation of nature at one remove.

These contradictory forces are also clear in another individual work, arbor temporis momentum – recedo, where King has created a startling bronze cast from a dead native bird – the iconic Kookaburra. The creature’s “pose” seems constrained in a distinctly un-avian way, as if this elegant, morbidly fascinating form had been retrieved from a Wunderkammer as a guity pleasure. The domestic tabletop suggests a private, rather than museum context, and paradoxical reproductive analogies abound as the bird seems to have emerged, foetus-like, from a substantial glass cylinder on the table, although it is clearly fully mature. Captured in exquisite lifelike detail in that most permanent of materials, bronze, it is nonetheless, clearly dead like a death mask.

In contemplating the bird’s demise, I was immediately reminded of Joseph Wright’s famous An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768), which also takes place on a domestic table in a room illuminated from the centre by chiaroscuro candlelight similar to the spot lighting appearing in King’s work. But in arbor temporis momentum – recedo, the scientist can grant no last-minute reprieve for the bird; it has already been expelled from the chamber as lifeless, to remain forever a mummified, metallic “wonder” or objet d’art.

Where Wright’s painting recreates the scene with its human protagonists enacting life science, King’s work avoids such direct human agency. In place of human observers, a large number of oval, or eye-shaped mirrors surround the exhibition space (arbor temporis momentum – speculo). But, as a further symbolic obfuscation, the mirrors are placed well below eye level to avoid capturing the gaze of the viewer, and rather than commanding a single-subject point of view, reflect the scene as unintelligible fragments in a dispersed geometry of refracted images.

This entire installation, and beautifully realised collection of human vanities – across the arts, science and nature as a collective Wunderkammer and shrine to the fragility of life, the temporary nature of existence and the barrenness of human systems is a superbly crafted memento mori for the Anthropocene. Here, each tabletop is like a station of the cross, as an alternative location or embodied moment. In arbor temporis momentum – respiro, another striking bronze bird occurs, seemingly discarded, on the floor. Notably, the artist has made no attempt to remove the casting sprue located directly above the bird’s heart, deliberately polishing it to a hard sheen so as to infer an artificial, external life force, introducing the Frankinstein element, also referred to in the glass vessels repurposed to suggest electric valves and bulbs, and other stand-ins for “elements”.

This poetic juxtaposition of near-eternal bronze, with the fragility of glass is another material fascination and constant highlight of the exhibition. arbor temporis momentum – flore features a series of large glass discs on the floor, layered upon one another like ripples on the surface of a pond. Yet this arrangement’s fragile beauty, complete with projected reflections onto the gallery wall, also renders the glass liable to be broken by passing feet. Greer Honeywill perfectly captures the precariousness of these formations in her exhibition catalogue, noting that “cylinders and discs threaten to roll or fall from their tables at the slightest vibration,” describing glass “as a recurring metaphor for anxiety and impending catastrophe.” [2]

In further reference to the impending (ecological) but also cultural collapse, arbor temporis momentum – chartam, includes a moth-eaten Australian flag as symbolic desecration, preserved in its fragility under glass on the floor as a paradoxical symbol and antiquated preserve of national identity. The glass flagpole stands naked above, a fragile lightning rod to its spent current (no longer flying proudly). In this way, across a raft of material and technical investigations, arbor temporis momentum, is both alien and also comforting in its familiar domesticity, as a preserve of ambiguous relics to represent the demise of the European enlightenment in this postcolonial, post-European settlement era, as a richly detailed material meditation and memento to a bygone era.

Footnotes