The image in art has been inextricable from the politics of copy versus original for a long time. Think of the ancients’ suspicion of representation lest it lure us away from the “truth”, or trompe l’oeil. Notable are the insights the Surrealists drew from musing on natural techniques of camouflage, or the vaunting of appropriation and simulation in the age of electronic media. This exhibition’s contention that mimicry, masquerade, and camouflage are particularly relevant in the age of social media may not be immediately compelling. Yet, how the dialectic between copy and original plays out always depends on underlying social and cultural conditions. The copy has at times been deemed politically suspect, at others “resistant” and transgressive. The question of what is at stake in claiming to be one or the other—given the different power dynamics each mobilises—is heightened by our immersion in digital visual culture. The inclusion of some historical works in Cover Versions acknowledges the continuity of these preoccupations along a number of different fronts, including nature, music, and screen culture.

A core concern is identity, one of the most enduring issues that artists have in recent years explored through mimicry, masquerade, and camouflage. As Surrealist Roger Callois once suggested after studying insect camouflage, identity depends on the negotiation of the conflicting desire creatures have to either stand out or blend in with their environment.[1] Or, as contemporary theorist Neil Leach put it, “The role of camouflage is not to disguise, but to offer a medium through which to relate to the other.”[2] While we might assume that camouflage and mimicry are strategies of protection and defence, playing a role in realising the living organism’s yearning to assimilate and become part of the world, they also risk “depersonalization through assimilation into space.”[3] We can become trapped in our own game as the disguise becomes the default. Or we can walk the knife’s edge, inhabiting mimicry and camouflage in self-aware, ironic and humorous ways that allow for difference to thrive.

Such tactics—including exaggerating dominant expectations to the point of absurdity in hyper-conformity, or turning the tables on prevailing power relations through inverting social roles—have long histories in negotiating race, gender and sexuality: Joan Riviere’s notion of womanliness as masquerade (1929) and Franz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952) are just two important theoretical antecedents. Yet, as Cover Versions demonstrates, contemporary artists continue to explore them, if now with a heightened awareness of the material stubbornness and complex intersectionality of identity. This is evident in the three works that form the heart of the exhibition, whose diverse registers but strongly tied concerns make for a powerful viewing experience: VERSUS (2001) by The Kingpins (Emma Price, Katie Price, Techa Noble and Angelica Mesiti), Frédéric Nauczyciel’s A Baroque Ball (Shade) (2014) and Yuki Kihara’s Culture for Sale (2014).

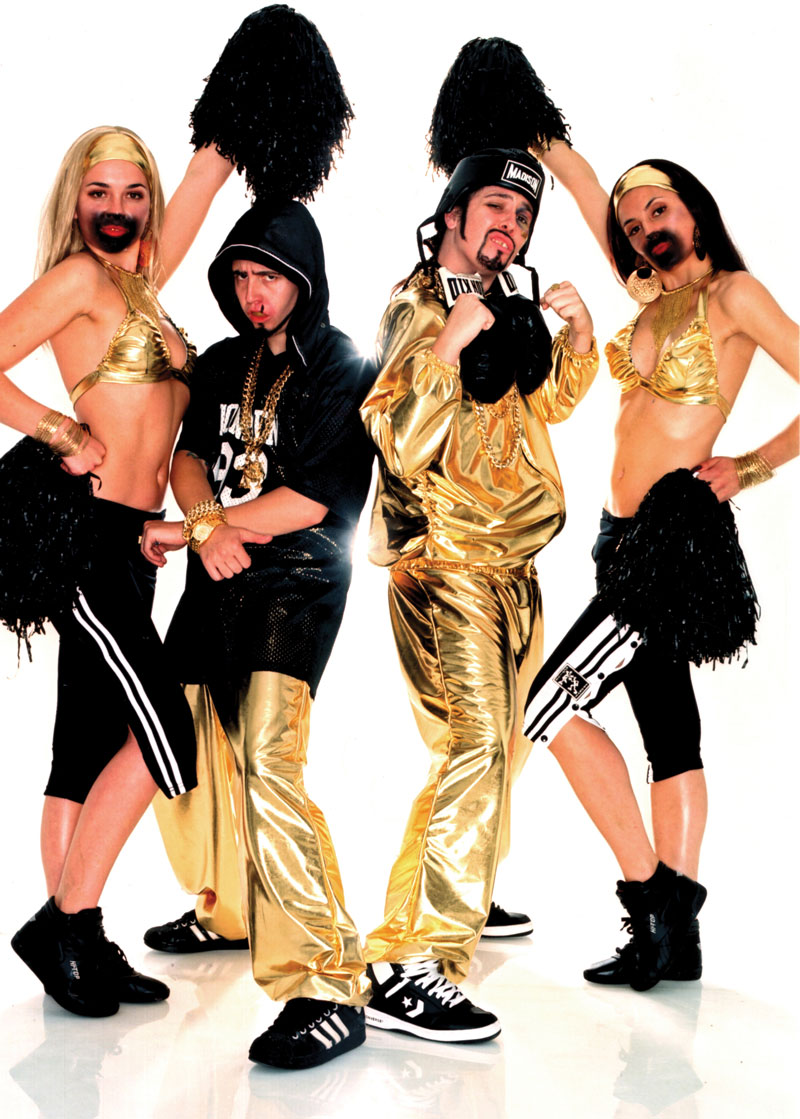

With its historical status and foregrounding of themes and visual strategies, VERSUS anchors the show. Decked out by turn in bling and Adidas, gold bikinis and beards, The Kingpins lip synch to the pioneering rap-rock hybrid Walk This Way (1986), Run DMC’s collaborative interpretation of Aerosmith’s cock rock original (1975). This is a virtuosic take on the cover version, synthesising the dramatic changes in music and approaches to originality between 1975 and 2001. Credited at the time with both facilitating the rappers’ crossover to the mainstream and reviving the aging rockers’ cultural relevance, Walk This Way also came to be defining for The Kingpins: VERSUS captured the zeitgeist of early video and gender mashing, but also embodied its critical limits. Not only can’t the female performers get past butt and tit feminine stereotypes, but it’s ultimately Aerosmith’s guitar lick and Run DMC’s beat that endure. In a move that highlights this imaginative gap, VERSUS also incorporates footage of Raw Sewage’s low-tech cover version of Walk This Way (1992) featuring legendary Australian performer Leigh Bowery, whose facility for creating entirely unique and confounding gender entities through radical costume and body modifications remains largely unmatched.

Bowery’s presence (if by the back door) lends the exhibition a further point of reference to reflect on how artistic approaches to gender and performance have changed since the 1990s, when Judith Butler’s influential theories on gender as performance first emerged.[4] Butler famously used as a case study Paris is Burning (1990), a film about the drag queen vogueing scene in New York City by white-American-gender-queer lesbian Jennie Livingstone that in recent years has attracted criticism for its alleged voyeurism and cultural appropriation. A Baroque Ball (Shade) (2014) by white French photographer Frédéric Nauczyciel addresses comparable subject matter, the queer ballrooms of Paris in current times. Nauczyciel’s video unfolds in real time in a single take, the ballroom an empty stage that is gradually populated with dancers of distinctive style who perform their mimicry with humour and insouciance, encouraged by cries of affirmation as the momentum builds. The simple mise en scene, including informal apparel, the Vivaldi score, and the collaborative rather than competitive energy, coalesce into a contemporary counterpoint to earlier representations of this vital subculture.

Also re-performing identity stereotypes through mimicry is Yuki Kihara’s Culture for Sale (2014), a five-channel interactive video installation where each screen portrays a single Samoan dancer who only turns on a smile and begins a personalized “traditional” performance once a viewer inserts a twenty-cent coin. This simple gesture is charged with complex associations: along with peep shows and the “human zoos” popularised by the nineteenth-century world fairs, it brings to mind some of Mike Parr’s performances where the audience is invited to cross an ethical boundary and knowingly exploit the artist in order to get the show started and justify their attendance. The cultural masquerade is survival but also strategic defiance. Its dark humour strikes a similar tone to Christian Thompson’s large-scale photographs, installed adjacent in museum vitrines, where the artist’s eyes peer out from behind images of colonial figures, a nod perhaps to another iconic work of Australian art, Destiny Deacon’s Forced into Images (2001).

![Frédéric Nauczyciel, A Baroque Ball (Shade) [Paris Ballroom Scene & Dale Blackheart (Baltimore)], 2014, digital video. Courtesy and © Frédéric Nauczyciel](/uploads/articles/SAM_3.jpg)

While identity takes centre stage, the exhibition fans out into other aspects of mimicry in art, such as those underpinned by an interest in natural camouflage—and its lessons in the age of climate crisis—as well as musical “cover versions” beyond identity. Stick insects and lyre birds, nature’s virtuosos of mimicry, dialogue across videos by Maria Fernando Cardoso (2004–08) and a decorated plate by Arthur Merric Boyd (c. 1948–58) from the Shepparton Art Museum’s famed ceramics collection. Michael Candy’s kinetic sculpture Synthetic Pollinizer (2017) grants us fresh insight into the fundamental role of bees in ecological health, including of the Museum’s immediate environment, by creating mechanical flowers that simulate pollination we can observe at close range.

Turning the Tables (1997–) by Loud Soft (Julian Day and Luke Jaaniste), which literally picks up one of the exhibition’s underlying themes, is a floor-based installation comprised of “prepared” turntables. They play K-Tel’s Hooked on Classics (1981), a bestselling album of well-known classical pieces all arranged with a pronounced disco beat that served to standardise the sound to the point of muzak. But this cover version, which given the physical interference plays the tunes idiosyncratically with bumps and glitches, ironically reinstates some of the compositions’ individual integrity: when the original has been so degraded and leached of content, it is the embodied and material reinterpretation that has purchase. This is a broader theme discernible in the works in Cover Versions, a thoughtfully curated exhibition which by foregrounding contemporary iterations of the politics of copy versus original reminds us of the difficulty and urgency of thinking in non-binary ways.

Footnotes

- ^ See Roger Callois, ‘Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia’, reproduced in Claudine Frank (ed.), The Edge of Surrealism: A Roger Caillois Reader, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 91–103.

- ^ Neil Leach, Camouflage, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006.

- ^ Callois, op. cit.

- ^ Such as Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990) and Bodies that Matter: On the discursive limits of sex (1993).