As I read the heading—Ismat Chughtai vs. The Crown—I broke into laughter. “Good God, what complaint does the exalted king have against me that he has filed this suit?”

Ismat Chughtai

In the Name of Those Married Women

In December 1944 the Urdu short story writer Ismat Chughtai was summoned to appear before the Lahore court. Her short story Lihaaf (The Quilt) had been accused of obscenity because of its unorthodox exploration of female sexuality. Fellow writer Saadat Hasan Manto had received a similar summons, and was due to appear before the Lahore court on the same day. Together Chughtai and Manto travelled from Aligarh to Delhi and then on to Lahore to appear before the court. After much debate, particularly across the sub-continent’s literary scene, the judge delivered a verdict in the author’s favour. In this instance, The Crown lost.

Only two and a half years later The Crown left South Asia. In the process, they divided the sub-continent. Lahore, which was now in a place called Pakistan, could no longer be reached from Aligarh, which was now in a place called India. A new border was drawn in ink on a map, and the sub-continent’s identity was irrevocably changed. Chughtai wrote: “The wretched urchins (children) did not realise that the English had left and, while leaving, had inflicted such a deadly wound that it would fester for years to come. India was operated upon by such clumsy hands and blunt knives that thousands of arteries were left open. Rivers of blood flowed, and no one had the strength left to stitch the wounds.”[1]

The exhibition I don’t want to be there when it happens has emerged from the wounds of this operation on its seventieth anniversary. Close to two million people died during Partition, in what is the largest mass migration in human history. And as Chughtai understood well, its wounds are still festering. “I’m not afraid of death, I just don’t want to be there when it happens” is a famous Woody Allen quote, but this is no laughing matter. The first iteration of this two-part exhibition, curated by Mikala Tai and Kate Warren, took place in August at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and featured artists from Pakistan and Australia who are exploring the psychology of trauma and anxiety in an era of perpetual conflict. With the involvement of PICA’s new senior curator Eugenio Viola the Perth iteration has expanded to include artists from India and place greater emphasis on the historical connection of South Asia’s Partition to the present moment.

The exhibition unfolds like a journey connecting India to Pakistan, South Asia to Australia and the past to the present. The works do not so much draw on the past but respond to a present that has been indelibly shaped by it. Although there is a deep poetry that permeates the show these works are the artists’ direct response to the worlds they are part of. Reena Saini Kallat’s Saline Notations (2015) greets Perth audiences with the familiar image of a beach where Rabindranath Tagore’s poem has been inscribed in salt, only to be washed away by the encroaching sea. Is this the same Indian Ocean that laps Perth’s shores? Near is Adeela Suleman’s curtain of hand-beaten tin birds, which also appear as a chandelier across the room.

These two works, After all it’s always someone else who dies (2017) and I don’t want to be there when it happens (2017), began as a cenotaph to those people who died from the violence in Suleman’s home city of Karachi. She set out to make one bird for every death. But she was unable to keep up with the pace because people were dying faster than she could hammer out a single tin bird. The work brings to mind the unsettling image of their making—the massive amount of energy required to produce one bird compared with the brutal instant of death.

The shadows cast by Suleman’s birds and Abdullah M. I. Syed’s razor blade drones create the image of a potential bloodbath should they ever collide. Their shadows hang like ghosts. The anxiety this produces looms over the work of Raj Kumar whose prayer mats made of 37,152 terracotta dice, allude to the gamble of faith in an increasingly polarised world that has seen over 35,000 people killed in terror attacks in Pakistan since 2011. From these artists we learn that the violence seeded by Partition is not historical at all.

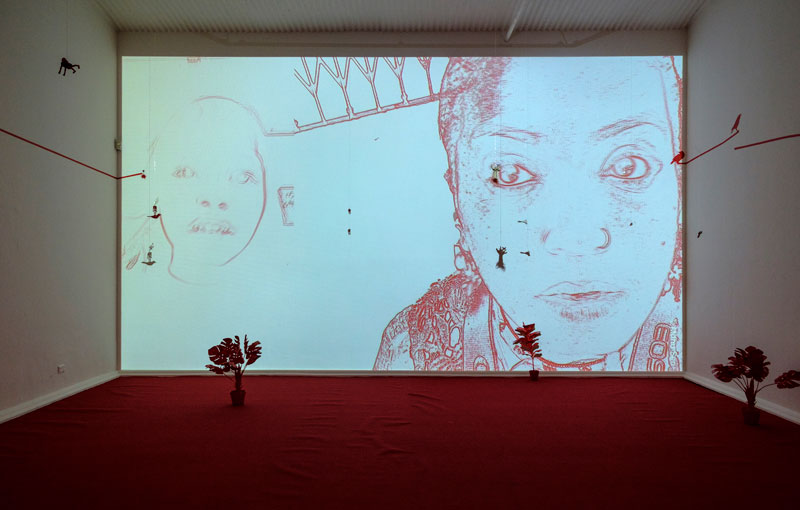

Into this scene Mithu Sen carries the human body. RIP—Another Time Another Stomach (2009) brings to mind the continuation of communal violence in India and its impact on the body and its psyche. Two androgynous human figures, maybe three, create a disorienting image with the body of a chook, a dragon and a lion gradually revealing themselves in the stillness of the image. This contrasts with the chaos of her video I have only one language, it is not mine (2014) which is based on an unscripted performance about the limitations of language in an orphanage for female victims of sexual and emotional abuse. The energy of this work carries the unmistakeable tone of trauma that is embedded in curious laughter. The video’s audio overpowers the space, but in doing so points to the generative value of silence that appears in Raqs Media Collective’s take-home piece The Translator’s Silence (2012–17).

Alone on the ground in its own room lies the video Earthwork (2016) by Sonia Leber and David Chesworth. An Australian suburbia, made from plastic toy models and other paraphernalia, has been destroyed—it appears like a handmade set in a Hollywood disaster film. This final work brings to the fore something Australia frequently refuses to believe; the horror of razor blade drones colliding with birds in mid-flight could happen here. In fact, it has. Just like India and Pakistan’s nation-making project, Australia is founded on a bloodbath. South Asia’s “operation” at the hands of the British took place in an instant. Australia’s was prolonged and sparse by geographic comparison, yet ongoing. This is the conceptual bridge between communities, places, and epochs that I don’t want to be there when it happens builds. It is subtle, but it is there. And it howls out at the present for peace and understanding even in the silences.

.jpg)

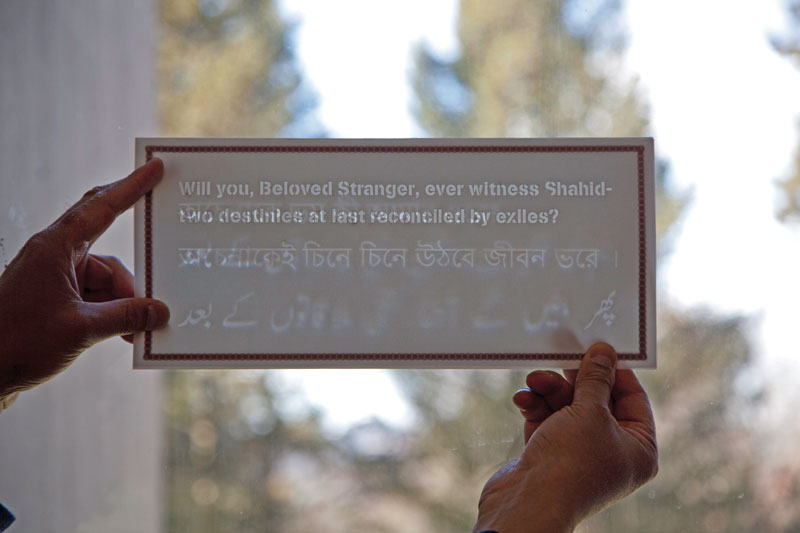

It is significant that no image of actual violence exists in this exhibition. The artists’ experiences are evoked in a lateral way that carries the intimacy of breath. And this is wonderful. Yet the very beauty in this subtlety means there is a substantial degree of contextualisation missing that may be required for many Australian audiences not familiar with the nuanced histories, identities and locations of South Asia that these works entail. One instance of this is the description of Agha Shahid Ali, whose writing features in The Translator’s Silence, as an “American poet”. Shahid, who was born and grew up in Kashmir, the subject of much of his writing, is also known as a Kashmiri poet and a Kashmiri-American poet.

Reading The Translator’s Silence as a work that features American, Pakistani and Bengali poets creates quite a different interpretation, in relation to the contemporary legacies of Partition, that would not be apparent if Shahid were recognised as Kashmiri. This highlights the complexities of prescribing a national identity and the dominance of the India/Pakistan narrative in South Asia further marginalising regions like Kashmir and Bangladesh. But this is not evident to audiences without background knowledge.

There is an urgency of the present moment found in the exhibition’s catalogue essay that is not carried into the exhibition with the strength it needs. This may be because the size of PICA’s space drowns the subtly of the individual works. I wondered why Earth Works appeared in a box and not as a projection spread across the entire floor or at least half of it. I wanted Suleman and Syed’s shadows to be bolder—striking various parts of each room and spilling out on to Kumar’s prayer mats. I wanted The Translator’s Silence to appear on something that was more significant than a plinth. While the space between works does not speak of urgency, it does speak successfully of the need for art to build bridges.

The Partition of South Asia defined and categorised people and land. Turning Ismat from person into Muslim—turning Aligarh from a place into India. Colonisation and nation-making has done this the world over. Its consequences lie in the heightened nationalisms and violence, which allows for Hindu Nationalists to run a supposedly secular India and the Australian government to close the book on the Uluru Statement from the Heart with one hand, while starving refugees on Manus with the other. I don’t want to be there when it happens is significant in the connections it forges across times, cultures and geographies.

There is wisdom here that Australia needs. This partnership between 4A and PICA is Eugenio Viola’s first curation in Australia. I will follow his work closely, as he looks from Perth out to the Indian Ocean through Italian eyes producing an exhibition program with PICA that may just compel us to think in more nuanced ways about the world as an interconnected community.

Footnotes

- ^ Ismat Chughtai, “Roots” in Lifting the Veil: Selected Writings of Ismat Chughtai, Katha 2000.