Female-centred exhibitions have been making their mark in Adelaide this year, following the big program of events and exhibitions staged for the inaugural FRAN Fest (short for Feminist Renewal Art Network) back in August. At the tail end of this, as part of the Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, Next Matriarch at ACE Open introduced an activist, political and female-forward discourse central to Indigenous experience. Co-curated by Yorta Yorta woman Kimberley Moulton and director of ACE Open Liz Nowell, the exhibition sets out to show how a revisioning of matriarchy can represent empowerment for Aboriginal women in a way that white Western feminism has historically failed to. Re-examining history through their art practices, the seven artists have made work that asserts their voice as contemporary sovereign women, acknowleding their autonomy as owners of this land and their continuing culture at a time of rapid change.

.jpg)

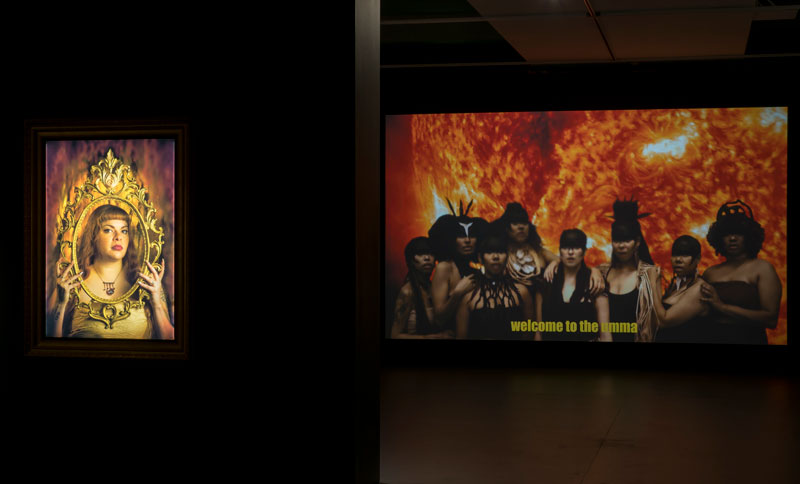

The exhibition is laid out across a series of rooms with dark painted walls. While each work was given its own space to capitalise on the individual potency of the works, the rhythmic hum originating from the soundtrack of Hannah Brontë’s video work permeates the space, drawing the audience into the gallery through its compulsive momentum. Umma’s Tongue-molten at 6000 ̊ is a bold vision from this Wakka Wakka/Yaegel woman. Brontë has adopted the cultural and visual language of hip hop, rap and pop music to talk about matriarchy and custodianship in a way that speaks to the music video generation. The fierce and uncompromising Aboriginal women depicted in the video appear to reach in and out of historical time.

Nowell and Moulton point towards this in their curatorial themes, discussing Indigenous poet Ali Cobby Eckerman’s Strings, they describe “a woman of great power, who draws her strength from the generations that sit either side of her; the matriarchs of the past and those of the future.” Brontë’s women are contemporary pop goddesses, and simultaneously represent the thousands of years of custodianship of the land. Brontë floats female warriors over images of mushroom clouds and cityscapes contrasted with hyper-coloured, lush rainforests and diverse natural landscapes. These divas project a sense of righteous anger about the fact that the world we are all responsible for maintaining has reached the point of potential collapse.

Although aesthetically disparate, Brontë’s warrior portraits can be compared to those nearby of Yanyuwa and Garrwa woman Miriam Charlie, whose photographs of women from her community command respect. The contrast between the spectacular and highly colour-saturated pop-culture influenced video work and the stark uncompromising reality of Charlie’s documentary-style photographs of daily life in Borroloola nevertheless strikes a chord. Similarly, Yankunytjatjara artist Kaylene Whisky employs a graphic, playful humor to compare the women in her community with superheroes, celebrities and pop-cultural icons in a painted diptych that celebrates Tjukurpa (ancestral stories) alongside representations of Dolly Parton and Wonder Woman.

Speaking to the matriarch more literally, as a woman who is the head of a family and mother of children, the three-channel video work Mother by Nicole Monks represents the transformative effect of standing at the cusp of motherhood. The artist’s filmed actions and naked presence before the camera powerfully articulate the way that a woman’s identity, her physical prowess and sense of self, is modified by pregnancy and the preparation for the birth of a child. Here, standing at a point of rupture, Monks tells a story about the emotional and cultural labour of motherhood and performs a series of mesmerising, symmetrical actions evocative of ceremonial dance. Her naked body appears to emanate from blackness, as if in the moment she is being born as a mother. Pregnancy weighs on her body, but also gives rise to new understandings to demonstrate what the body is capable of. As a woman of Yamatji Wajarri, Dutch and English heritage, Monks is grounding herself, drawing on collective knowledge and willing this new life into the world.

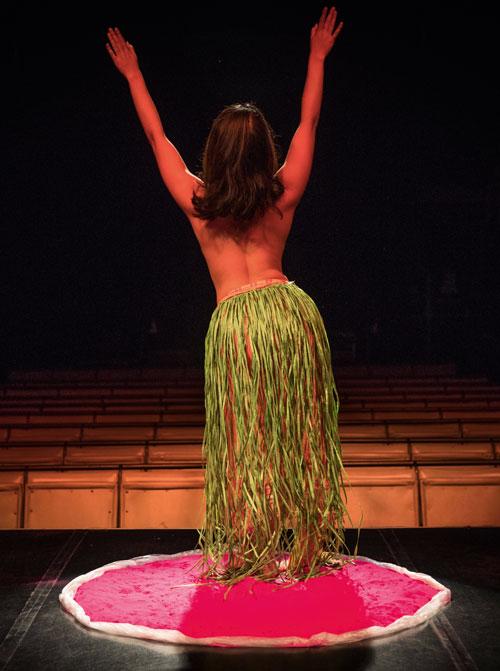

In another compelling video work, Amrita Hepi’s Dance Rites explores ideas of cultural authenticity. A Bundjulung and Ngapuhi (Māori) woman, Hepi invokes the aura of the exoticised other of the traditional dancer performing dance rites, not unlike scenes of the chieftain’s daughter in the 1962 film of Mutiny On The Bounty or Lisa Reihana’s retake in scenes from In Pursuit of Venus (infected). Hepi’s hypnotising rhythmic movements ripple over each other in various screen takes, her lithe body draws attention to how these movements come naturally, embodied by the dancer. But, unlike Reihana’s historical reimagining, it is her contemporary body, it is her dance. Hepi roots this work in the present through the mirroring of a red sand platform in the video and on the gallery floor. The footprints in the sand echo her on-screen presence and prove her occupation of the space as a real body, not just a performer on a stage.

.jpg)

As the polemical discussion around Indigenous sovereignty and feminism made clear in the public forum for Next Matriarch, history is littered with instances that serve white women at the expense of women of colour. These viewpoints are exposed in the works by Ali Gumillya Baker, a Mirning woman from the Nullarbor and west coast. The defiant gaze of her lightbox photographic portraits sovereignGODDESSnotdomestic disrupt domestic space by reinserting the unspoken story of Indigenous servants. These portraits are more than just tokenistic memorials to women in her family, there is a real sense of agency and indignation. Likewise, Wemba-Wemba and Gunditjmara artist Paola Balla reflects on her personal and family trauma, and the impact of European colonisation on the lives of Indigenous women.

The opening after-party and performance event Fempre$$ curated by Hannah Brontë played out a parallel story to the exhibition, allowing the artists to take to the stage and perform their empowerment. The event opened with Amrita Hepi calling to the audience “all black femmes to the front,” invoking Kathleen Hanna’s riot grrl catchphrase from the 1990s. It’s an invitation to Aboriginal women to claim that space, and for non-Indigenous people to take a step back. In that moment Hepi set the tone for the event, introducing activism through movement and dance. Rather than speaking back, these artists are speaking up. It’s not a backlash, or a retaliation, it’s a whole new conversation and the women depicted are critical and unwavering. While the impacts of colonisation and generational trauma still persist, the shift is now to empowerment. The patriarchy is drowned out by calls to action from Brontë and stared down by Baker. Women drive the conversation: what is it like to be a body, to be a woman, to be a custodian, to be a matriarch, to be a mother, to be a sister? The title of the exhibition points towards a future, the next matriarch, as a call to arms for women to construct the future that they want to be part of.

.jpg)