In Michael MacGarry’s video Excuse Me While I Disappear (2014), a young man sweeps the paths of an empty city of newly built apartments. It seems an innocuous portrait until we learn that the city is in Angola, and was built by the Chinese in an oil deal after decades of civil war. Only a few can afford to move here from the nearby city of Luanda, that is by contrast crowded with slums. The empty city stands as a monument to the uneven relations between Africa and China, that is now the biggest economic power on the continent. Excuse Me showed at Another Antipodes: Urban Axis, an exhibition billing itself as the first survey of African contemporary art in Australia. Another Antipodes is also the name of a new organisation that wants to go on creating opportunities for artists between the continents. In this first show they largely drew upon South Africa and Zimbabwe, countries once known as “White Africa” because they were ruled by white elites until well into the twentieth century.

In Mary Sibande’s I Decline, I Refuse To Recline (2010) a black mannequin wears an oversized dress that billows around her on the floor. Its design is Victorian era, while its fabric and colour are that of the domestic worker in current day South Africa, hybridising the servitude of black women in nineteenth century and twenty-first century capitalism. Namibian artist Nicola Bandt also works with colonial era dresses, photographing Herero women in the extraordinary costumes they adopted from German missionary women. They stand on scenic landscapes that we learn are the sites of a genocide of Herero people. After the German army left, Herero men began to wear their military uniform as well, as if to imbibe the immense power they had shown in their occupation.

Such legacies resonate in Australia, where artists also work with the histories of colonialism and racism. The current Documenta14, in Athens and Kassel, features three artists dealing with the nation's history: Bonita Ely, Dale Harding and Gordon Hookey. Yet the Australian representation in international exhibitions pales in comparison to the success that African art has achieved outside of Africa over the past decade. It was only in 2012 and 2015 that two of the world’s leading curators, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and Okuwai Enwezor, brought Australian Indigenous artists into the main exhibition halls of Documenta and the Venice Biennale. This, in spite of Enwezor's history of ground-breaking postcolonial exhibitions, and Christov-Bakargiev's view that Indigenous art is of no interest internationally.[1] The reason for this disinterest lies in the fact that while Australian artists have embraced postcolonialism, unlike Africa, our nation is yet to be decolonised, with Indigenous peoples subjects rather than sovereigns.

The contradiction had its apogee in 1989, when Anne-Marie Willis and Tony Fry published influential essays in Art in America and Third Text, accusing the Australian artworld of committing ethnocide by commodifying Aboriginal art.[2] They argued that Aboriginal art’s success carried on a kind of feel-good primitivism that was damaging rather than reparative for Aboriginal people, who were being colonised all over again. It was thus not possible to speak about Aboriginal art because its artists could not speak for themselves. African artists, on the other hand, were no longer indigenous, but members of postcolonial nations and thus the modern world.

So it was that the “new internationalism” of the artworld of the 1990s included both the new African nations and the old Soviet bloc countries, but did not include indigenous artists. But these artists, who succeeded in persuading the European artworld that African art was no longer primitive, were not truly African. It was instead the African diaspora, artists and curators who were as indebted to their experience with European institutions as they were to their experience of Africa itself. This was partly because the African continent lacked much of the institutional support needed for African exhibitions, forcing curators and artists to push themselves upon the well-heeled European artworld.

The Algerian-French artist Kader Attia, who is showing this year at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne, became famous without ever having exhibited in Algeria. Attia’s work in Australia comes via shows in Paris and Venice, and juggles the signs of Africa to create a redemptive experience for audiences versed in the wrongs of European history. The MCA’s online interview with Attia emphasises the way his work affects a “repair” of objects, so that in his exhibition there there are carvings by unnamed Senegalese sculptors, shelves of publications that represent and reflect on the colonial-era, and a room of shrouded, praying figures.[3] The wrongs of primitivism, colonisation and Islam are here under reparation, in a therapy that both creates and overwrites history with sensibility of anxiety.

Of such representations of Africa, the writer Tsitsi Darembanga says, “I mean one has to ask, into whose interest do certain images play?” This, in an installation by Rabia Williams and the Zimbabwe Women’s Film Co-operative in Another Antipodes. The installation is a work in progress, zim.doc (2010–), in which the filmmakers try to map out their lives in Zimbabwe in an interactive, online format. Darembanga is speaking of those images of Africa that cycle in and out of Africa itself, images that constitute “five centuries at least of propaganda that tells you you’re inferior, and anything that another black person tells you to do is probably wrong.” Invented and then invented all over again by colonial and postcolonial governments, Africa stands between images of tribalism, war and zealotry.

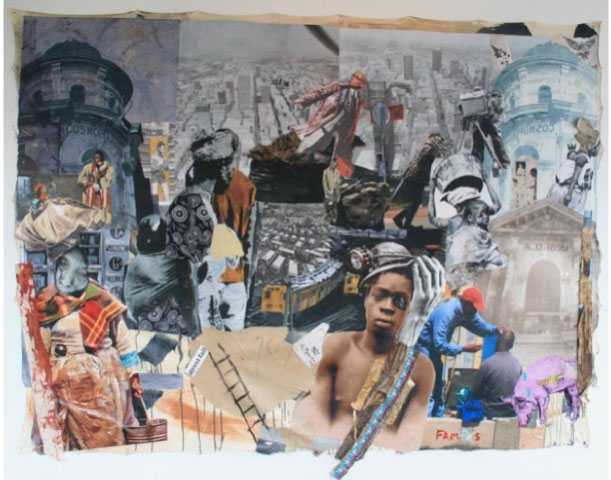

Much of the better work in Another Antipodes grapples with this kind of complexity, with the extremes by which Africa is typically understood. The urban axis of the exhibition’s subtitle describes large paintings, photographs and collages that image these extremes in Africa’s cities, the artists holding chaos into a glance. Wycliffe Mundopa’s The Bonfire of the Vanities (2015) is a massive hyper-colourful portrait of grotesque human shapes arranged into tight, overlapping and baroque textures. Ayanda Mabulu’s Blame It On The Boer (2016) is a banner of angry and suffering people pasted onto torn and roughly cut images of urban Africa. Mabulu is well known in South Africa for his classically inspired scenes of African rulers rimming and performing oral sex, and he was recently condemned for a painting of the President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, buggering Nelson Mandela.

In Web-Jacket (2015) the brilliant Congolese artist Maurice Mbikayi dances in a suit of computer keys tied by cables and telephone cords. Mbikayi will freeze to death at the end of this video, while also gripping the suit to his body, as if killed by the very thing that he seeks to save him. In the photographs of artist Jake Michael Singer a chaos of bodies, fabrics, pipes and crumpled metal overlay each other to produce a complex, hallucinogenic vision of the city. Bending distance and gravity, they appear to be digital collages, but are in fact carefully performed compositions.

These are not only pictures of Johannesburg rooftops but analogies for globalisation and its cities, in which extremes play themselves out side-by-side. Such works express what Maria Elisa Cevasco has called the “Brazilianification” of the planet, in which gated communities, hijacked high rises and slums butt up against each other.[4] In such a world it is no longer possible to use nations as allegories of the experience of human life. Instead this experience consists of the juxtaposition of extremes, of navigating barbed wire and border crossings. Australian Indigenous artists best represent this dilemma of a post-national artworld. For as it has become standard practice to declare one’s allegiance to Indigenous nations, to belong to the Noongar and Wiradjuri, or the Kalkadoon and Yorta Yorta, the nation is itself losing its currency in the international artworld. This is why this artworld relies increasingly on diasporic artists who represent the eclipse of national identity itself.

There is no better symbol of this transition than the Johannesburg Art Gallery, the largest on the continent and once an icon of the newly minted Union of South Africa. Today it is reduced to having a trickle of visitors, its priceless collection of European paintings unseen because it is simply too dangerous for outsiders to navigate the neighbouring streets. People at the bottom end of global capitalism have overtaken this national symbol, butting up against its Romanesque facade with a sprawling street market. So it is that the relevance of African art for Australia may not lie in our shared histories of colonialism, but in a shared future in which the experience of global capitalism becomes increasingly difficult to navigate.

Footnotes

- ^ See Fiona Gruber, ‘Only connect, not compete as artists converge on Kassel for Documenta’, The Australian, June 9, 2012. For the story of Enwezor’s ‘dismissal of indigenousness’ see Ian McLean, ‘Modernism without Borders’, Filozofski Vestnix XXXV, no. 2, 2014, pp. 121–139 at 137 at http://fi2.zrc-sazu.si/sites/default/files/fv_2014-2.pdf.

- ^ See Tony Fry and Anne-Marie Willis, ‘Art and Ethnocide: The Case of Australia’, Third Text 5, 1988–89, pp. 3–20 and ‘Aboriginal Art: Symptom or Success?’, Art in America 77, no. 1, July 1989, pp. 109–117.

- ^ See https://www.mca.com.au/exhibition/kader-attia/ and Artlink review: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4609/kader-attia/.

- ^ ‘Globalization and Indigenous Cultures’ conference, Zhengzou University, China, 2004.