And as our ship pulled in to Circular Quay

I looked at the place where me legs used to be

I thanked Christ there was nobody waiting for me

To grieve, to mourn and to pity.

Eric Bogle, “And the band played Waltzing Matilda”

Eric Bogle’s anti-war, anti-nationalist ballad is an irresistible starting point for this review. Its geographic reference to the site of Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art and its moralising pathos, as well as its post-national spirit of irony, draws deep parallels with Kader Attia’s exhibition. It suitably captures the eponymous spin on war and conflict, difference and othering, the damaged body and the walking wounded.

Leaving the sharp winter sun of Sydney Harbour for the MCA’s darkened chambers after a long march through the three venues hosting The National, Attia’s ambition comes across as rich in substance and form. Here, the artist had pushed his ideas to the heart of the matter through raw and explicit means. The sentry work J’Accuse (2016) takes the primitivist bull by the horns in an assembly of roughly-hewn wooden busts of grotesque deformed faces and displaced trunk-like limbs. Like the film from which J’Accuse takes its name, it’s a monument to the futility and dread of modern industrial warfare. But more than this, it implicates the culture and discourse of modernity – its battles of identity, nationalism and avant-garde modernism – in the senseless terror of war. The cubist realist style of the carvings draws a direct affinity between the latest surgical methods used to repair the horrific wounds caused by modern weapons during WWI and Picasso’s modernist vivisections. The other reference is colonialism – underlined by the outsourcing of the carvings to African artists – a recurring motif in Attia’s work: if J’Accuse takes its departure from the Great War, Attia reminds us that it was not just a war between European powers, as it is often portrayed, but the war machine of Western imperialism in action.

In J’Accuse we stand among misshapen soldiers of misfortune entranced by French filmmaker Abel Gance’s J’Accuse. First released as a silent film in the aftermath of WWI, J’Accuse was hailed as a classic anti-war film by European critics, but like Dada, its avant-garde artistry (the original was hand-tinted in violet and rose) made more impact than its pacifist message. Nineteen years later, on the brink of WWII, Gance was compelled to remake his work. Its title had even more resonance then, as it originates with Emile Zola’s 1898 open letter to the French President defending an imprisoned Jewish officer, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, for allegedly leaking military secrets. Dreyfus, a nineteenth-century Chelsea Manning or Edward Snowdon, was a victim of the anti-Semitic hysteria that so shaped those times.

As part of Attia’s installation, the film is a reminder of historical repetitions. In agit-prop revolutionary zeal, maimed and displaced war victims rise in revenge from their graves dispelling their fate as heroic monuments of nationalistic propaganda. Two developments add to the dramatic scenography of the 1938 cut of J’Accuse. One was the introduction of sound; the other was the willingness of veterans to parade their deformities before the camera, delivering what has to be the ultimate cinematic riposte to Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935), glorifying the flawless eugenic body.

Trauma and its repair, manifested in the scar, are recurrent motifs for Attia, as in his work for dOCUMENTA (13), The Repair: From Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures (2012). In the Australian exhibition, The Culture of Fear: An Invention of Evil (2013) explores similar ground using the structures of the literary archive. Metal shelving in DIY industrial chic evokes the decommissioned filing stacks of another century, the texts crudely bolted to the shelves. These crowded rows of “endless columns” are part memorial to the enduring human capacity for fear of difference, and part attack on the brutalities of modernity and its expansive reach. Graphic imperialist adventure fantasies from the pages of Journal des Voyages et al. reveal violent fetishistic images of savagery, cannibalism and ritual killings.

Positioned adjacent to J’Accuse, the excess and repetition of The Culture of Fear reminds us that brutality and tyranny are not requisitioned to earlier centuries. Othering is a fait accompli that goes hand in glove with modernity and, as Attia drives home, even the subjects haven’t changed. In the 21st century, tabloids and entertainment industries are no less explicit, Time and Le Figaro show us as much. Bloody terrorism, political totalitarianism and religious extremism are alive and well, from IS to Al-Qaeda, as the continuing reverberations of colonialism.

Enter the artist. Based in Berlin and born in Paris in 1970, Attia was raised on the textures of intercontinental crossings between French suburbia and the stony ground of Algeria. His is a hybrid intellectualism, his fluency in transcultural patios and Western art and philosophy typifying the global contemporary artist. Further, he believes in the power of art to manifest change – “to be a part, not apart”, to act, not to represent – and he is well placed in the chronology of Ranciere’s aesthetic regime in which all art is inescapably political. Attia is a shamanic expressionist who, in comparison to fellow Algerian Albert Camus’s fictional outsider, makes ennui as apartness seem like an existential luxury – an artist who is not implicated in the narratives of his world, and who makes no attempt at its repair, is an artist lost at sea.

An advocate for social justice and a disciple of the current relational, interactional timbre of contemporary practice, the social community both constitutes and informs Attia’s work. In Ghost (2007–17), the collective is modelled on the numerous bodies of local volunteers. Assuming the devotional posture of Islamic prayer, the faceless faithful kneeling in rows like the crosses that now decorate the world’s battlefields, create a homogenous community – a ready allegory for a secular audience of the coercive tribalism of organised religions, wars and nationalism in which the individual is so easily lost to the collective.

As any gamer will testify, the military aesthetic is a powerful intoxicant and it gives Attia much of his ammunition. This is not unsurprising, given that his parents lived through the Algerian War (1954–62). Tightly constrained by the low-slung corner of the gallery, Asesinos! Asesinos! (Murderers! Murderers!) evokes an animated horde gathered in restive protest. Though megaphones affixed to old doors, the work’s arte povera materiality recalls Attia’s highly affective Kasbah at the 2008 Biennale of Sydney’s Cockatoo Island site, where audiences were invited to walk over a shanty-town of corrugated iron. But in parts the target feels too soft: a plaster wall evoking a mortar blast and a mosaic of stained glass shards is overly orchestrated, its implication of terrorism too neatly packaged. Attia’s work is at its best when the discord that is its subject is unresolved. In assembling his work, like a philosopher, he sometimes loses the argument. This is most clearly the case in his photographic juxtapositions and collages which share the innate aesthetic logic of French rationalism and reveal a natural stylist without hope of escaping his skin.

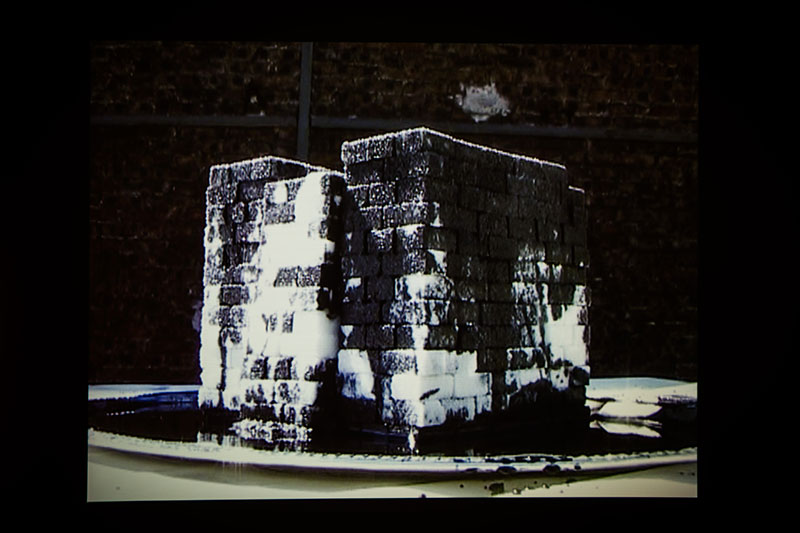

The implicit inequities of the world inherited from the age of imperialism – economic, political, religious, cultural – are root themes throughout Attia’s oeuvre, and doubling is a tried and tested strategy. Oil and Sugar #2 (2007) documents a white sugar cube eroding under a rain of black oil and references the Ka’aba at Mecca, core to Islamic faith. At a stretch, the construction of black and white identities is also called into question. Of similar concerns, The Debt (2013), a word-play on Africa’s fiscal liability to the IMF operates through double slide projections to illustrate in flash-card fashion the many ways in which African nations repay the “debt” to Europe, not least the labour market of slavery, military service and, added to this, the elemental forces of African art. The message is inescapable: the contemporary is embedded in the past, the 21st century in the 19th century. For Attia, the wounds of modernity have not been healed by the promise of transnationalism and globalism, but he nevertheless ventures to enlist the artist’s arsenal as a means of reparation.

Attia’s panacea has a particular resonance in contemporary Australia, in the aftermath of our ongoing celebrations of WWI and perennial grapplings with such site-specific wounds. In 2015 the mythology of the Anzacs was endlessly reinforced in centenary commemorations across the country, with women and Indigenous servicemen duly added to the canon. But while the immense losses on a Turkish beach embedded in the national psyche are made explicitly visible, the deeper psychological scars of colonisation are worn much closer to the chest. To paraphrase Attia, the fin de siecle and inevitable transition we are living through is akin to an open wound that must be healed before we can brave the future. Australian audiences, both black and white, take this duty seriously, as many of the artists in The National also demonstrate. Whether manifest as victim, impartial witness or guilty inheritor, this is the conscience call for our age. Nowhere is this metaphor more atavistic than in Attia’s film on phantom limb syndrome, in which sensation is felt long after amputation.

Critics (John McDonald and Christopher Allen) have challenged Attia’s use (we assume) of cheap labour in the outsourced carvings to unnamed Senegalese and Congolese as hypocrisy and evidence of the artist’s de-skilling, along with his clichéd postcolonial critiques. Indeed, as Santiago Sierra’s work repeatedly shows, the artworld is a well-oiled cog in the exploitative wheel of capitalism, and the agile contemporary artist is well accommodated in the elite social class. Whether we seek consolation in Attia’s moralising or lose ourselves in the indecent pleasures of significant form, his greatest hits owe a debt to the modernism that is the object of his critique and infatuation. It is worth noting that his favourite artist and most discernible influence was Picasso, whose artefacts wore their scars with great heraldry.