The first major analysis of the concept of sovereignty in Western culture was undertaken in the sixteenth century by the French jurist, economist and philosopher Jean Bodin. Against the political turbulence of France, the ongoing wars of religion between Protestants and Catholics, and the rivalry between church and state – with princes, kings and the Pope each competing for ultimate authority – Bodin was keen to determine what it was exactly that constituted sovereignty. In his Six Books of the Commonwealth (1576), Bodin set out to comprehensively define the term. Drawing on both his legal training and much thinking about his own historical context, Bodin was able to distil the fundamentals of sovereignty into a handful of principal attributes.

The sovereign could be an individual, such as a prince, or a small or large assembly, but in order to be truly sovereign had to meet four criteria. Firstly, the true sovereign had to be supreme, meaning no authority was above him. Secondly, he had to be absolute in the sense that no tribunal could undermine this authority. Thirdly, his power needed to be indivisible, that is, he held ultimate decision-making in matters of law, warfare and the appointment of magistrates. Finally, sovereign power needed to be perpetual. Sovereignty was in essence a state of being above and beyond all forms of political jurisdiction, for as Bodin put it, “The true sovereign remains always seized of his power.”[1]

Bodin’s political theory became highly influential on future political philosophers and set the foundations of sovereignty as we understand the term in the modern state. All of which makes the current exhibition at ACCA, Sovereignty, compelling for its own affiliation with the term. Developed in partnership between ACCA director Max Delany and Gundjitmrara/Wembla woman Paola Balla, Sovereignty presents a selection of works made by First Peoples of South East Australia and takes as its focus the concept of indigenous sovereignty explored through the works of 28 artists and artist collectives.

Until the 1960s First Peoples were denied basic human rights – including the right to vote – granted to Australian citizens. Recognition of indigenous Australians as formal citizens ostensibly occurred through the 1948 Nationality and Citizenship Act, but the continuity of discriminatory practices and social exclusions meant that this recognition was only partial. The socio-political condition of First Peoples post-colonisation has represented the polar opposite of Bodin’s view of sovereignty; indigenous peoples being condemned to states of systemic disempowerment.

As a result, the call for indigenous sovereignty has been enacted through multiple campaigns over the last fifty years to challenge Federal and State governments for cultural acknowledgement. As political scholar Raia Prokhovnik notes, Aboriginal sovereignty has several meanings, including: firstly, and perhaps most importantly, an overturning of the legal ruling of terra nullius and the recognition of indigenous peoples as traditional custodians of the land; secondly, the notion that the First Nations never surrendered to British occupation; thirdly, the necessity to acknowledge sovereign identity through enshrinement in a treaty; fourthly, that Aboriginal culture with its distinctive ceremonies and rituals is itself a form of inalienable sovereignty. Finally, sovereignty asserts the claim for equal inclusion in the Australian political economy free from discrimination and violence.[2]

What is most evident in the varied works in Sovereignty is the heightened awareness that for more than two centuries of colonial occupation indigenous sovereignty has been deeply undermined. This is poignantly conveyed through a suite of short videos, InDigeneity: Aboriginal young people, storytelling, technology and identity (2014–16), made as part of a series of digital storytelling workshops by indigenous young adults graduating from the Richmond Emerging Aboriginal Leaders program at Korin Gamadji Institute. In one video, the young video-maker Tallara Sinclair asks her peers how they feel Aboriginality is perceived in the wider culture. The answers they give are hard-hitting and revealing. Indigenous people, they avow, are branded “criminals”, “homeless”, “dirty”, “illiterate”, “uneducated”, “alcoholic” and “dole-reliant”.

As specific pejoratives these adjectives represent an aggregate of over 200 years of settler attitudes to the First Peoples and a colonial legacy of appropriated land, incarceration, genocide and forced assimilation policies resulting in ongoing histories of dispossession, trauma and cultural fracturing. If the original function of these descriptors has been to invalidate indigenous peoples, such terms are reappropriated reflexively by several of the artists in Sovereignty as forms of trenchant critique.

Megan Cope echoes Sinclair’s tactical use of language in her work Resistance (2013) which captures the more generally xenophobic attitudes of non-indigenous Australians on immigration through a series of placards, laid in a pile on the floor stamped with the words “The Big Steal”, “Queue Jumpers”; “Assimilation”, “Entitlement Scheme”, “No Advantage”. Tangentially, language is employed in the vernacular of agit-prop by Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance (WAR) – a collective established in 2014 of young Aboriginal people committed to activism – in their posters decrying colonial invasion and the histories of genocide.

Included in the fifteen banners stretched over the gallery walls is a banner featuring a screen print of the now infamous photo of Dylan Voller, hooded and tied to a restraining chair at the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre in Darwin which circulated in August 2016 amidst revelations of the Centre’s systemic abuse of its young charges. Most confronting is a banner titled Massacre Map Victoria 1836–1850 (2014) which details 68 occurrences of killings across the state by year and locale as a chilling inventory of racial genocide.

For the English seventeenth-century philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, sovereignty was formed by the voluntary bestowing of a collective of individuals’ power into a single governing figure or assembly who would, in exchange for the power bequeathed to him, govern and protect the social whole. Hobbes believed that without such a political framework, human nature, with its tendency to vengeance and pride, would inevitably descend into chaos and warfare or “that dissolute condition of masterless men”.[3]

In other words, the figure or assembly who assumed the role of sovereign embodied the political commonwealth – an entity which by mutual covenants, would assume the forfeited authority of each individual in order to ensure peace and common defence for all. With its pre-condition of a certain kind of body politic involving the voluntary transfer of rights into the figure of the sovereign who would defend the commonality, one can see the antecedent to a contemporary model of representative democracy. The kind of racist violence graphically described in the banners made by WAR, highlights the potential travesty of this brand of sovereignty when the state does violence to its subjects instead of offering them sanctioned protection.

But according to the contemporary political scholar Dimitris Vardoulakis, sovereignty is an exercise of power that reveals itself precisely in the justification of violence. It is a relational ontology of power that rationalises itself in terms of the legitimacy of the sovereign. Absolute sovereignty operates as the determinant of law and justice, means and ends, and war and peace. These terms are separated and reunited through the power of the sovereign, whose pronouncements are ultimate. In other words, the sovereign possesses the prerogative to exercise its own mode of justice. As political theorist Carl Schmitt states in the opening to his Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.”[4] That is, the sovereign not only grounds legality but also places him or herself beyond the law: the sovereign may violate the law, in order to assert his or her sovereignty.

In light of this, Steaphan Paton’s juxtaposed works in Sovereignty: two short videos Cloaked Combat #3 and Cloaked Combat #2 (both 2013) alongside three paper cloaks titled The Magistrate, The Officer in Charge and Yours Faithfully the Sheriff (all 2016) represent a reappropriation of this dimension of sovereignty as the state of being beyond the law. The videos depict Paton using a bow to launch arrows into a bark shield in the East Gippsland landscape. This area is particularly known for brutal colonial conflicts and the dispossession of its traditional people, the Gunai.

Although Paton uses high-tech archery equipment, the scene conjures up an historical relationship to the land and ancient tribal practices. In further contrast, the installation of cloaks is fabricated not from the traditional material of possum skin but photocopies of infringement notices, stitched together like a quilt. The notices are for multiple unpaid council fines and infringement penalties (such as driving an unregistered vehicle) as well as outstanding warrants for arrest. The Officer in Charge comprises multiple photocopies of a single outstanding warrant for the unpaid sum of $265.30 with the accompanying threatening text.

If you do not finalise this matter immediately the Sheriff may seize and sell your property or if insufficient property is available to satisfy the value of the warrant, you may be imprisoned after having appeared before a Magistrate.

What this pro forma letter of course indicates is the sovereignty of the State, brought home by its punitive tone. As Bodin declared in his Six Books, “the principal mark of sovereign majesty and absolute power is the right to impose laws generally on all subjects regardless of their consent.”[5] What makes Paton’s work powerful is the abrasive juxtaposition between sovereignty as a sense of cultural practices dating back thousands of years premised on a connectedness between humans and the land, versus the ill fitting place of the indigenous peoples in a political economy that makes them subject to penalties and threats of imprisonment for not conforming to municipal laws. Paton’s crafting of the infringement notices into a form of armour represents a wilful defiance of State-imposed sovereignty – a deflection that re-instates himself as sovereign.

This capacity to make exceptions or exclusions is for Schmitt, the quintessential quality of sovereignty. Similarly, according to Vardoulakis, even under the guise of democratic political systems the logic of sovereignty continues through processes of exclusion, meaning that those who are ostracized are exposed to violence. Briggs (Adam Briggs) expresses vital dissent from this kind of exclusionary politics by contesting it through the appropriation and modification of a vernacular of resistance in his rap video Bad Apples (2014). In a retaliatory idiom he chants the lyrics, “You call them ‘good for nothing’, I call them cousins, brothers sisters. I still love them.” Briggs’ video rejects disenfranchisement through positioning himself in allegiance with his indigenous peers in an act of symbolic restitution.

An alternative view of sovereignty was proposed by the eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau in The Social Contract (1782). In the famous first line of his first chapter, he declared, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”[6] While Rousseau recognised the authority of the state, his political theory was motivated by the urge to wrest back freedoms for citizen-subjects from under the potential authoritarianism of state rule. He was vehemently opposed to the notion of political masters. Instead, Rousseau’s central idea in The Social Contract was the concept of a “general will”; the collective opinion of the citizenry.

The social contract was a liberal political process whereby each individual bequeathed their original sovereignty to the state for the purpose of the common good. The general will always tended towards equality because it had the collectivity of its members rather than a ruling elite, in mind. In giving himself to no authority embodied in a single person, the individual citizen instead gave himself to the citizenry as a whole. “By becoming part of the general will,” Rousseau wrote, “the citizen is like a small sovereign. Each is an ‘indivisible part’ of the general will.”[7] In this way, each member of the citizenry would share in the power of sovereignty. “It is solely by this common interest that every society should be governed,”[8] Rousseau proclaimed.

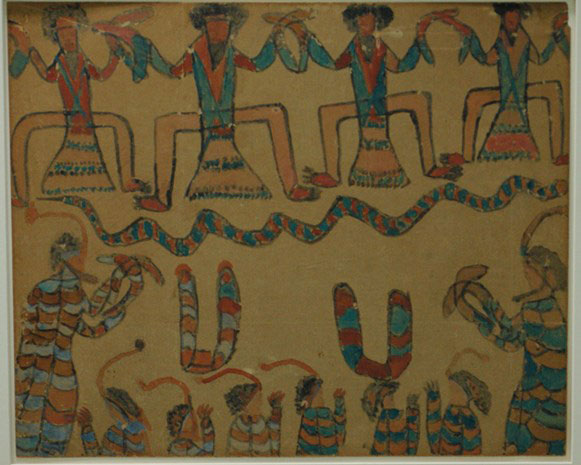

This redefinition of sovereignty as an inclusive form of participatory politics chimes with Bruce McGuinness’s digital video (originally a 16mm film) Black Fire (1972) which captures the Zeitgeist of the early 1970s as an era of nascent Aboriginal activism. The year the film was made coincides with the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the lawns of Parliament House in Canberra as a declarative demand to recognise sovereignty of the nation’s First Peoples. The film intersperses wide-ranging footage of corroborees, football matches and even McGuinness’s anthropology lecturer at Monash University speaking about indigenous patterns of kinship. Most interesting is the footage of young members of the Black Studies Group, a student organisation at Monash University emerging as part of the black power movement.

During the filmed discussions the members speak of the importance of agitating for change, for increased recognition of indigenous culture through Land Rights and the incorporation of indigenous history into university curriculum, while lamenting the parlous statistics on Aborigines living below the poverty line. The kind of discriminatory exclusions characterising white Australia represents the antithesis of Rousseau’s understanding of sovereignty, antithetical to the privileging of one demographic at the expense of another. The radicalising of the indigenous students portrayed in McGuinness’s video corresponds with Rousseau’s notion that the ultimate political project is the regaining of an originary freedom, lost under repressive political regimes built on structural inequality.

While Rousseau’s concept of sovereignty might betray a type of regulative idealism, its general precept that political economy should not be based on oppression nor mastery of one individual or class over another, represents a paradigm that is perhaps the closest approximation to an indigenous concept of sovereignty as freedom from colonial imposition. What the artists assembled in Sovereignty remind us is that literal and symbolic acts of violence and political “othering” must be called out: disclosed in order to be critiqued. As the banners and placards in the works by Sinclair, WAR and Cope attest, a colonial Australian imaginary with its implicit racism still persists. And yet, as the end of McGuinness’s film advocates with its last frame bearing the single word “beginning”, potential exists for new acts of political revision. Only in this way can a re-imagining of the restorative possibilities of sovereignty emerge.

Footnotes

- ^ Jean Bodin (trans. M.J. Tooley), Six Books of the Commonwealth, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1967 (first published in 1576), p. 25.

- ^ See Raia Prokhovnik, ‘From Sovereignty in Australia to Australian Sovereignty’, Political Studies 63(2), 2015.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, Oxford Univerity Press, London, 1996 (first published in 1651), p. 122.

- ^ Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, MIT Press, Cambridge, 1985, p. 5.

- ^ Bodin, op cit, p. 32.

- ^ Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, 1762: http://www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/rousseau1762.pdf p. 1.

- ^ Rousseau, ibid, p. 1.

- ^ Rousseau, ibid, p. 12.