Because the mountain grass

Cannot but keep the form

Where the mountain hare has lain.

W.B Yeats

In the second stanza of his 1919 poem, “Memory”, Yeats speaks to memory’s impress – to the way the earth holds the form of a body long after it has gone. Sappers & Shrapnel, curated by Lisa Slade for the Art Gallery of South Australia, similarly gathers together historical works made by soldiers in action or convalescence and contemporary responses produced by eleven artists and artist groups from Australia and New Zealand. For me, much of the exhibition’s interest lies in its implicit examination of memory – personal and collective – and the ways in which memory is invariably distended by myth and invention. While mythmaking may reside at the heart of memorialising practices, the exhibition avoids the often grandiose confection found in volumes of military history and novels alike; its approach by comparison, solemn, considered, yet also dynamic.

At the core of the exhibition is a dark display space – an inner chamber – in which objects made during the First and Second World Wars are lit vividly as reliquaries. Often fashioned from battlefield debris, as carvings, sculpture and elaborate engravings, these objects speak to a human need for beauty and the wilful urge to create. An embroidery made by Private William George Hilton in a convalescent home between c. 1916–18, replete with thatch cottage and downy swan, sets a sequence of linked associations in motion: Hilton’s delicate palette recalling that of Paul Nash’s obsessive renderings of the sea wall at Dymchurch (where he went to recover from war strain in 1921); the solemn verse of Wilfred Owen and, paradoxically, the savage prose of Günter Grass; as well as photographs recovered from a grandparent’s loft portraying a starved yet smiling man. Hilton’s work is one that philosopher Gaston Bachelard might have termed a “poetic image” – a form that resonates beyond itself, connecting the distant to the deeply personal.

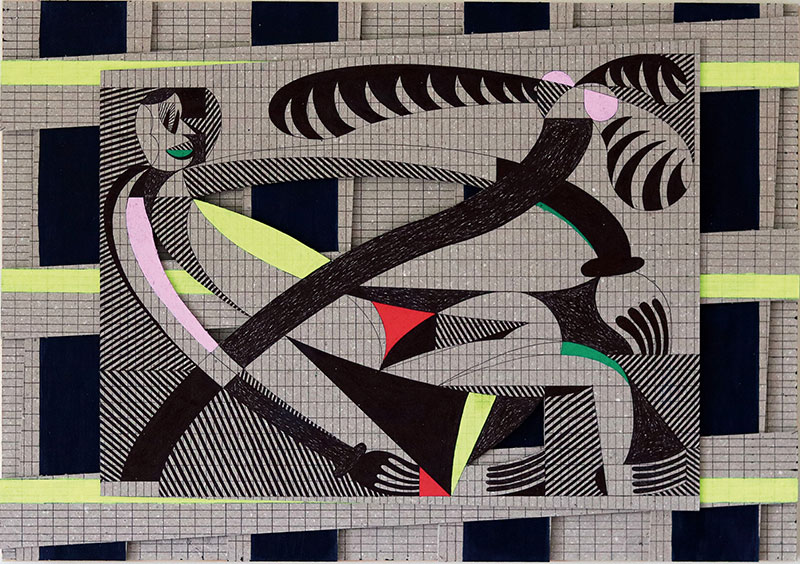

Alasdair McLuckie and Sera Waters are two artists whose works fill the nebulous space between memory and invention. Using trench art drawn from the Australian War Memorial collection as a starting point, McLuckie’s Seven Dreams for E.G.P. Sullivan (2016) transforms jungle imagery taken from a pillowslip embroidered by Corporal Edward Gordon Patrick Sullivan, into fluorescent, cardboard bas-relief. McLuckie’s art often relies on the queer rupture caused by layering dissociated images, yet the effect of this series is not one of cool surrealism but a quixotic and concerted endeavour to draw a link between one artist and another through time.

Front-line on the Home Front: Remembering Johns (2015–16) by Sera Waters was inspired by an assemblage of influences: a blanket recording a visual history of war service, fashioned by Corporal Clifford Alexander Gatenby (1941–45), and the imagined demise of a host of her antecedents, each endowed with the name John. This dense embroidery is a sort of family field (as opposed to a tree), a topography of a battlefield that slowly reveals a boot, a leg, a mask only by way of protracted looking. A related work, Remembering Johann (2016), is a decorative mat adroitly metamorphosed into a death mask. This is what Waters does so well – expanding the domestic to accommodate an elastic repository of connotations.

Olga Cironis is an artist whose work I was not familiar with. The strange numismatics of Echo (2015–16), part relic, part talisman, in which ungainly tendrils of human hair are rabidly stitched to found medallions, are among the more unsettling works within the show. “I am interested in layering memory”, she said in her artist’s talk. Considered intently, these small works give up their piecemeal stories. Inscriptions can be made out on the medals, and one can hazard a guess at the look of the person from whom the hair was shorn. Hair, a peculiar substance that dies as soon as it ascends to the surface of skin, expresses life and lifelessness, a changeable material much like memory itself.

Not all of the contemporary works were underpinned by remembrance, tainted as much by melancholy as romance. Nicholas Folland, for example, adopted a more formal approach. Intrigued by dazzle camouflage, his installation True Blue and Green (2016) comprises revolving colour discs that frustrate the viewer’s gaze and cause the eye to shift impatiently over a horizontal span of moving pattern. Baden Pailthorpe’s film Cadence (2013), in which the manoeuvres of soldiers are slowed and blurred into hypnotic, refracting streams, is a reminder that art is not only employed as a response to war, but is integral to it; whether evidenced by showmanship, deception, or as artillery that signals then fuels the war itself (consider the 1937 Entartete Kunst exhibition as among the earliest of a series of increasingly horrific acts). Similarly, intricately carved shields by Brett Graham, a descendant of the Ngati Koroki Kahukukura people of Aotearoa, appear as formal visual exercises, but are intended as symbols of place in which indigenous peoples were maimed, mistreated or exiled. That the ANZAC spirit figures less prominently in non-indigenous national identity than acts of racially motivated cruelty is a compelling statement.

Perhaps the most difficult work in the exhibition is that of Ben Quilty, whose installation Dresses for Soulaf (2016) descends from recent experience not distant recollection. The artist recently travelled to Lebanon, Lesbos and Serbia with author Richard Flanagan, to meet "the great river of Syrian refugees”. A panel discussion led by Quilty with Flanagan and World Vision representatives Ralph Baydoun and Conny Lenneberg drew a large audience and brought the focus of the exhibition, if only momentarily, to current rather than past conflicts.

Comprising moving image, drawing, soft sculpture and his archetypal Rorschach patterns recast in lifejackets collected from the beaches of Lesbos, Quilty’s installation is disjointed, materially convoluted and at times awkwardly installed. His related show, The Stain, held between June and July at Tolarno Galleries was, by comparison, more refined and incisive. Yet many of the constituent parts of this new installation were produced collaboratively with refugees and support organisations. The installation speaks directly to the trench art specimens at the core of the show and demonstrates art as a healing device and social document as distinct from intellectual or formal aesthetic inquiry. It feels ungenerous, even imperceptive, to assess a work of art according to the conventional parameters of criticism when the work functions so far outside of that system, but a short film, The Dress (2016), perhaps the most eloquent component of the installation, presents a sequence of vignettes about refugee seamstress Raghda, beautifully although tenuously held together by a quartet score. Ultimately, and perhaps indicatively, its loose, distracted narrative leaves its subject adrift.

While the exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated publication most of the essays are too brief to perform any function other than preliminary description. There are exceptions: the lead essay by Nicholas Saunders sets trench art in an historical context; Elle Freak’s text on Sera Waters is considered, concentrated and elegantly written; Ryan Johnston touches on the wealth of recent war art scholarship, notably Eleni Holloway’s study of soldier knitting, in his assessment of Fiona Hall’s All The King’s Men (2014–15); while Richard Flanagan’s contribution (an adaptation of a longer essay published in The Guardian) is minimally although powerfully expressed.

For me, the effect of this exhibition was of resonant impress given that the majority of the contemporary works were motivated by rumination not impassioned dissent (Tony Albert’s Universal Soldier, 2014, is a notable exception). At times I hoped for more strident, provocative work, although the measured disquiet of the exhibition set it apart from other recent shows of protest – from Okwui Enwezor’s All The World’s Futures, Tate Modern’s Citizens and States or See You At The Barricades at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Supported by the ANZAC centenary art and culture fund, Sappers & Shrapnel could have clung to a nationalistic rhetoric that flared in the 1980s and was employed in the Howard era, and beyond, as further call to arms. Instead, Lisa Slade has assembled an acutely sensitive exhibition that offers gravity in the wake of far lighter-hearted offerings in the eastern-seaboard summer shows.