"We declare that the splendour of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed”, wrote Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti more than a century ago in his Manifesto of Futurism. “A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath … a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

One can’t help but wonder how Marinetti and his fellow Futurists would have fared behind the wheels of a Tesla, in which the engine’s grunt and roar is replaced by a soft electric hum, self-driving software overriding the intoxicating rush of freedom and release. That’s not to say that the car is no longer more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace, but Murray Art Museum Albury’s exhibition Speed: The Fast and the Curious suggests it is a different form of beauty today.

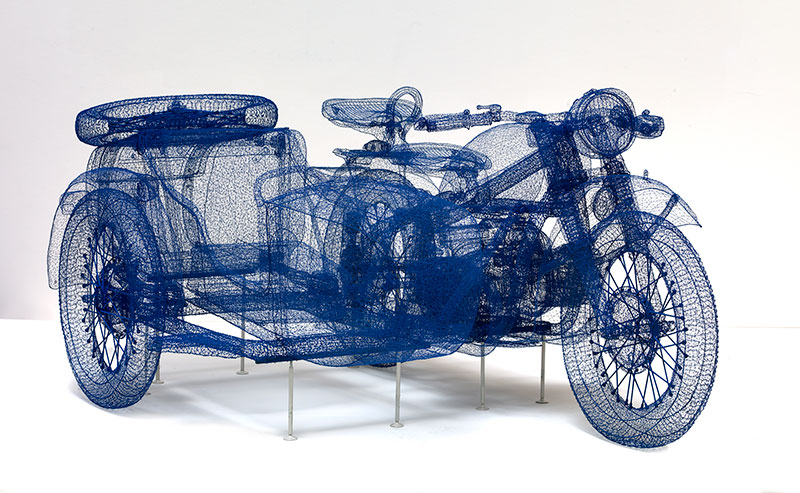

Throughout the show, the masculine energy of the automobile that so seduced the Futurists is neutered: shrunk in Matthew Liersch’s plastic and balsawood miniature Ford flat bed truck, all weight and substance sapped in Eamon O’Toole’s plastic moulds of motorbikes and Shi Jindian’s crocheted steel wire Chang Jiang. In the centre of the museum’s Paul Ramsay Galleries, Will Coles’s car, Memorial (2014), rusts iron-red from disuse.

Rather than a symbol of speed, the car comes across as a flawed, human attempt to achieve speed, vulnerable in its weighty materiality as an object. This is made all the more poignant by the timing: the exhibition’s run coincides with the closure of Australia’s oldest car maker Ford’s Broadmeadows factory and Geelong engine plant. As the country’s car-manufacturing industry screeches to a halt, it seems that the world, dragged along by cold, hard economic facts, moves faster than any Falcon.

It’s especially apt for Albury, home of Drivetrain Systems International, which for 43 years employed thousands of locals to build gearboxes for Ford, Holden, SsangYong, Maserati and Mahindra; the company’s Lavington factory closed in 2014. Not far from the city lies the Hume Weir Motor Racing Circuit, left disused and in disrepair since 1977.

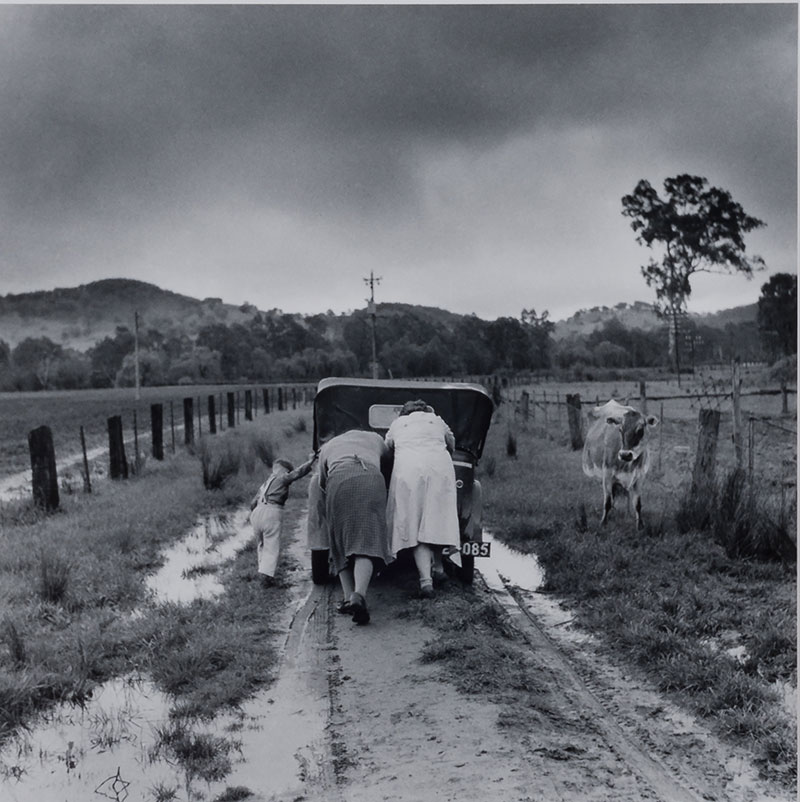

But Speed is more than just a paean to redundant machinery. Here, the car represents a static marker by which one can measure the speed of history and technological progress. In many of the works, the machines function more as a backdrop. The true story is played out in the sidelines in which the car is just part of the scenery in an evocative passing parade captured in photographs by Narelle Autio, Rex Dupain, Jeff Carter, Bronek Kozka, Belinda Mason, Tracey Moffatt, Patricia Piccinini and Jozef Vissel.

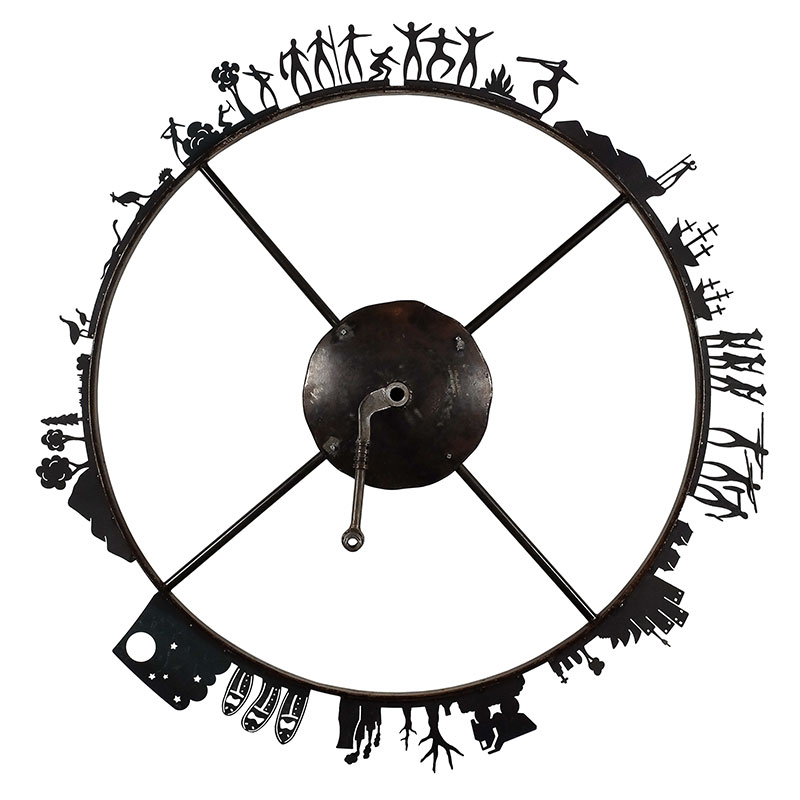

Across the diverse practices surveyed in this exhibition, speed is a presence more implied than described – a pastoral scene here, a modern city there, painting here, 3D computer modelling there. The progressive redundancy of the machines act as markers for the passing of time and the inexorable crawl of Australian history, culminating towards the end of the exhibition in Darren Wighton’s provocative Wheel of Misfortune (2015) that enacts the story of Australia from a Wiradjuri perspective. Turning a crankshaft, it’s the only work that puts you in the driver’s seat to negotiate the landscape and force some important questions. What is to be done? How do we rectify our past mistakes? What are we leaving behind and what are we heading towards? For all this haste, are we getting anywhere at all?