One's mind and the earth are in a constant state of erosion, mental rivers wear away abstract banks, brain waves undermine cliffs of thought, ideas decompose into stones of unknowing, and conceptual crystallizations break apart into deposits of gritty reason.[1] Robert Smithson

The earth, with its stratified layers, flowing terrain and towering cliffs is a rich analogy for the mind. The earth, like the mind is responsive, adaptive and shaped by unseen forces. Throughout human history artists and theorists have sought to articulate the relationship and chart the intersections between ourselves and the environment. Phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty suggested that the body and the earth are “two segments of one sole circular course … which is but one sole movement in its two phases”.[2] This idea that humanity and the earth are part of a cycle, that they are interdependent parts of a whole, is common to many fields of research. Anthropologist Tim Ingold has extended these ideas suggesting that we are in fact only able to exist as sentient beings if we also consider our world as sentient or somehow capable of subjective feeling: “It is not possible … to be sentient in an insentient world: In such a world, light, sound, and feeling could figure only as vectors of projection in the conversion of objects into images, rather than as qualities of experience in themselves”.[3] Instead Ingold proposes that “… every living thing, our human selves included, is irrevocably stitched into the fabric of the world”.[4]

And, while claims of this nature are contentious, they do point to a commonly understood notion that the world and our selves are in some kind of delicate balance. It is accepted that human activity during the Anthropocene is known to have irrevocably altered the natural cycles of the earth. The tentative balance of old is now enduring a realignment of untested dimensions.

And so, what is it to treat the earth as a readymade as Nick Mangan does? In Mangan’s recent survey exhibition Nicholas Mangan: Limits to Growth, at Monash University Museum of Art, he presents five major bodies of work, each of which uplift or isolate events and locations that operate like readymades. Mangan considers these locations and events sculpturally, treating each element within his chosen moment or place as material, which is then rendered and reflected upon. As Mangan’s states in the catalogue: “they are entirely sculptural actions, only they do not produce static sculptural objects. For me, these gestures are actions that narrate and animate the temporal features of the material in question; they unearth the stories held within the material”.[5] To unearth a story from within the earth is to imagine that the earth is sentient, that it has harbored a tale of its own. Mangan’s materials are sculptural actions which react and adapt in a fluid way, reflecting the circle of influence and impact in Merleau-Ponty’s diagram.

Mangan approaches his sculptural material with even-tempered measure as a collector of evidence, engaging in reenactment, documentary montage and specimen collection to present a situation through its artifacts or outcomes. Despite this objective, quasi-scientific approach to his materials, Mangan’s political position is evident through the exhibition’s title – Limits to Growth – which refers to a 1972 report commissioned by the Club of Rome that analysed a computer simulation of the impact of human systems upon the earth. The simulation tracked the consequences of exponential economic and population growth in the face of the Earth’s finite resources, finding that two out of three of their simulations would result in “overshoot and collapse” of global systems by the end of the 21st century.

In Mangan’s earlier work there was an emphasis on the materialisation of an object’s inner forces. Whether these are a photocopier’s animated internal workings, as in Elemental Exposure (2003), or an explosion of energy from an abstracted motorcycle chassis, as In The Crux of the Matter (2003), Mangan isolated and made errant forces visible. In the more recent projects on display at MUMA the forces at work are macroscopic, overtly political, embracing a broader social context, as evidence of disharmonious forces and the imbalance between humans and nature. Instead of imagining these moments of collision and disruption embedded in a specific object, they have become visible through specific actions and conflicts as systems and energy flows diverted that Mangan identifies in the world.

With the earth as his material, Mangan also sheds light on the conflicting forces that shape it. As Smithson claimed: “In order to read the rocks we must become conscious of geologic time, and of the layers of prehistoric material entombed in the Earth's crust”.[6] But, as made clear within Mangan’s work, Smithson’s geologic time is no longer the earth’s only relevant time frame. Instead, the forces of economic time with its push–pull of supply and demand have overridden this ancient tempo resulting in a clash between extraction time vs. geological time.

The idea that we can apply a human time scale to geology is a fundamentally incorrect proposition perpetrated by the extractive industries. This false assumption that the mineral reserves Australia relies upon are inexhaustible ignores the fact of their creation. The fossils that we are burning to generate energy are the product of millennia of geological activity, and yet are extracted and processed in a matter of weeks/months/years.

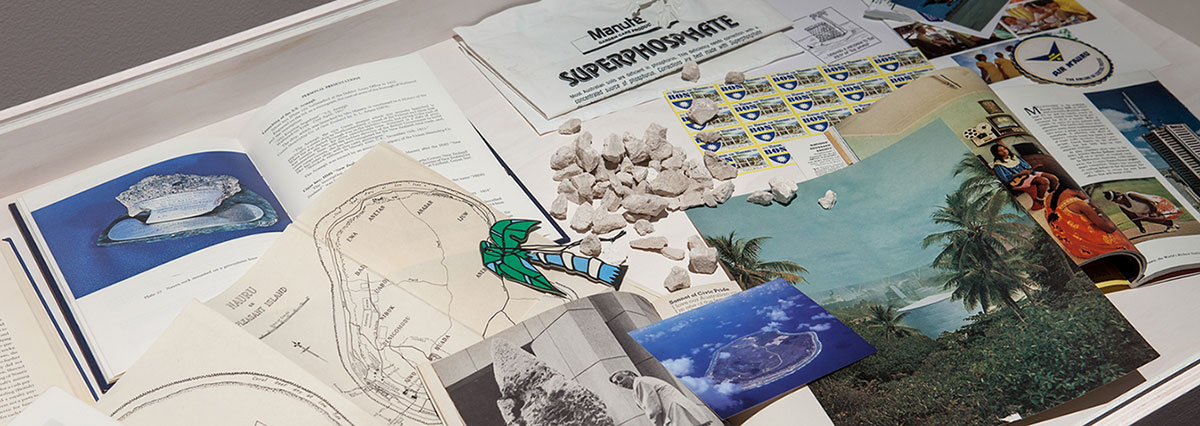

Nauru – Notes from a Cretaceous World (2010) draws on the island of Nauru’s unique environment as sculptural material, tracking what happens when a natural environment is radically disrupted. On Nauru, it is plain to see the collision of a geological and human time scale. It took millions of years of very particular conditions – specifically, the deposits from passing birds accumulated atop decomposed marine life – to form this distinct rocky, coral limestone substructure. But once the British Phosphate Commission stumbled upon these valuable deposits in the 1920s and initiated strip mining, intensified during the 1970s, it took only three decades for the island to become a hollow, disembowelled void, with its centre removed, to resemble a crater.

Mangan’s filmic essay as part of the installation Nauru – Notes from a Cretaceous World explores the island as a readymade. There, in the wasteland of broken machinery and the cracked ruin of this churned, infertile and scarred surface is a landscape that represents ignorance and greed. Mangan’s filmic montage of broken satellite dishes and dead earthmoving equipment represents the inert detritus of a once-mighty country. After mining this island nation to a husk, President Dowiyogo’s last act of office on his deathbed was to suggest that the remnants of the land be turned into coffee tables. Mangan carried out this tongue-in-cheek command with Dowiyogo’s Ancient Coral Coffee Table (2010), a work cut from the coral limestone boulders in the forecourt of Melbourne’s Nauru House (a 1970s skyscraper that stood as a monument to Nauru’s wealth). This work sets the scene for Nauru’s current source of income from the Australian Government, as a cruel and inhuman offshore detention centre for Asylum seekers who attempt to travel to Australia by boat. The work can be seen as the ultimate parable of a country’s fall from moral grace.

Again, in Progress In Action (2013), Mangan isolates a specific moment in time and place – the indigenous rebellion against Rio Tinto on Bougainville Island – and teases out the socio-political implications of this situation, which came about when the harmony between humanity and the natural environment was disrupted. Similar to Nauru – Notes from a Cretaceous World, Progress in Action pits the vested interests of a mining company against those of the local people in a work that can be read as a sculptural agglomeration of forces in the clash between technological and geological time, resulting in a vast physical chasm.

.jpg)

In the 1970s an Australian subsidiary of Rio Tinto began mining for copper on Bougainville Island in Papua New Guinea without first gaining consent or offering adequate compensation to the local Indigenous people. An enormous open pit began to form in the jungle of Bougainville, as both the physical gulf and expression of the divisive impact of opposing forces. The frustrated indigenous Bougainvilleans formed what became known as the Bougainville Resistance Army and then went on to blow up the mine’s power station, disrupting the flow of power, literally and figuratively. This act of rebellion, quashed by the PNG Government, who denied the Bougainvilleans food, fuel and medication, forced the BRA into exile in their own territory. With flows of power and resources blocked, they drew on their own resources, creating productivity where there was opposition. By using the abundantly available coconuts as a fuel source the BRA refined the oil into biofuel, which powered their resistance.

Political philosophers, such as Chantal Mouffe, attest to the generative nature of conflict in promoting ideas of “agonistic pluralism”. Agonism, as the process of engaging hegemonic power structures in conflict, so as to materialise opposition, works to strengthen existing liberal democratic structures. Mangan’s Progress in Action continues this line of enquiry by drawing attention to the productive self-determining outcome of this clash of forces. In this work Mangan uses the fact that the BRA fuelled their own rebellion by working with nature to suggest an alternative way of employing nature to serve human needs. To demonstrate this point Mangan reconstructs the coconut biofuel refinery used by the BRA revolutionary army to power a generator, in the gallery, which in turn powers a projector screening Mangan’s film of montaged news clippings charting the events of the BRA revolution.

As such, Mangan tracks forms of control and locates them, analogously, in the generation of power. Power is control and control is power. Mangan refocuses this chain of command by reiterating that Power – a human necessity – is always generated by nature, giving nature the last word.

The work that became the title for this exhibition, Limits to Growth (2016), is an investigation into the dematerialisation of power through the decentralisation of money. In this work Mangan disrupts and undermines the neo-liberal urge toward “growth” by using solar panels to power a bank of servers in the MUMA basement that manufacture Bitcoins, the digital currency that can be created by anyone using open-source software.

Mangan contrasts this with the human-sized currency once used by the people of Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia. Known as the Rai, these enormous circular discs were carved out of limestone and were used up until the beginning of the twentieth century as currency. These coins physically connect the earth with a concept of value, an idea shared by the extractive industries. But while the Rai appear to be at the material end of the currency spectrum, they were in fact often traded orally, with their movement and location remembered through a complex system of storytelling rather than actual physical placement. In fact, there are stories that tell of Rai being thrown overboard to stabilise the canoe, their whereabouts at the bottom of the sea carefully recorded, as their value and ownership persisted regardless. Mangan purchased and photographed a number of Rai using bitcoin that he had generated in the MUMA basement. This complex interweaving of transaction and displacement reveals the most salient aspect of this process to be the flow of value from a crypto-currency to one that can be tracked through story.

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Despite the apparent dematerialisation of currency, and the Anthropocene’s general disregard for the earth’s might, the mother of all natural forces, still dictates the conditions of our survival. The sun is at the heart of our most basic time structure, and its force controls our food source and our orbit. Ancient Lights (2015) – first created for Artspace, Sydney, and Chisenhale Gallery, London – draws attention to the sun and its energetic capacity.

Projected opposite each other are two videos, one using a high-definition image of a spinning ten peso coin to highlight the sun’s central role in our collapsing world. The peso spins on an axis, seemingly seconds before collapse, yet the looped film ensures that the peso is hinged, endlessly, at the tipping point “negating the heat death of the universe” as Mangan puts it.[7] The second video is a montage charting various human methods of tracking solar activity and its outcomes: the vast gemasolar plant near Seville, Spain; images of tree-rings taken at the Laboratory of Tree Ring Research, University of Arizona; and Russian biophysicist Alexander Tchijevsky’s chart that attempts to correlate sunspot activity with human activity (including revolutions, insurrections and migrations from the 5th century BCE to the 20th century ACE). In an interconnected chain of logic, each projector is powered by solar panels, ensuring that the sun powers a film about its own power.

In this exhibition, Ancient Lights culminates as a kind of microcosm of Merleau-Ponty’s circularity. Whereas Progress in Action and Nauru – Notes from a Cretaceous World isolated moments of geological imbalance or dislocation from natural cycles, Ancient Lights looks to the sky to reveal the endless intersections of influence and impact that define our relationship with the environment. In a gesture of optimism, this work contemplates the sun’s mighty cycles, showing how we might align human energy and our commercial imperatives with solar-powered energy into some kind of ultimate balance, where we can draw on what shines above, rather than what burns from below.

Footnotes

- ^ Robert Smithson ‘A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects’ (1968), in Jack Flam (ed.), Robert Smithson: Collected Writings, University of California Press: L.A, 1996, p. 100.

- ^ Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Claude Lefort (ed.), Alphonso Lingis (trans.), The Visible and the Invisible, Northwestern University Press: Evanston, 1968, p. 139.

- ^ Tim Ingold, “Toward an Ecology of Materials”, The Annual Review of Anthropology, Issue 41, 2012, p. 437.

- ^ Ingold, ibid, p. 437.

- ^ Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth, Sternberg Press : Berlin, 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Smithson, ibid, p. 110.

- ^ Mangan, ibid, p. 160.