The fraught relationship between Poles and Polish Jews is the subject of a major exhibition by the Jewish Museum of Australia. Can We Talk About Poland? features the work of two Melbourne-based artists, author and photographer Arnold Zable and photographer Lindsay Goldberg. A period of two decades separates their encounters with Poland; Zable undertook his first journey in 1986 in his early forties; Goldberg made several trips between 2013 and 2015 while in her late teens and early 20s. The photographs bring together two historical periods capturing the internal dynamics of the different life stages of the photographers in a penetrating reflection on identity and place.

Zable travelled to Poland in 1986 by way of the Trans-Siberian railway on what he describes as a “personal quest” arriving in the Eastern border town of Bialystok; the town is the birthplace of his parents, grandparents and forefathers. Over the course of several months he visited the surrounding area and explored the cities of Krawkow and Warsaw where he met, amongst others, four of the last pre-war Jews living in Bialystok, young Poles rebuilding the Tykocin synagogue and activists in the Solidarity movement.

Zableʼs colour photographs document the countryʼs rural life – both its bucolic landscapes and material deprivations – as well as the vestiges of Jewish monuments and decaying Communist infrastructure. Using a SLR camera and shooting in colour, Zableʼs images have a soft, blown-out analogue quality that infuses the works with a woozy softness.

For Zable visiting the country for the first time was a personally transformative experience, one that he subsequently shaped into narrative for his award-winning memoir Jewels and Ashes, published in 1991. At the time of the bookʼs release some 25 years ago now, I attended an emotional book reading and signing by Zable held by the Australian Institute of Polish Affairs (also cultural partner of the exhibition). It was one of the first meetings organised by the organisation, who were part of a broader global movement seeking to create dialogue and engender understanding between Poles and Polish Jews. The relationship, centuries old, was ruptured in the wake of the invasion of Poland by the Germans in 1939, the subsequent establishment of death camps and murder of 6.1 million Jews (3.5 million of them Polish Jews) on Polish soil. For many Holocaust survivors and their children – and for Poles themselves – it was still the recent, unspeakably painful and traumatic past.

The complex nature of the relationship is reflected in the exhibition itself and the care with which it has been curated, the excellent didactic panels that go to great pains to offer a fair appraisal of history and it extends to viewing the exhibition. The title of the exhibition, itself an open question, contains the recognition that for some Poland will never be a safe subject. It re-examines the relationship that many have with a country that is both “home” and a place of horror. For some, like Zable and Goldberg, and Polish Jews returning to the country of their forebears, developing a relationship with the country has been an enriching experience and brought about a closeness to both Polish and Yiddish culture. For others – captured in excellent filmed interviews on several screens throughout the exhibition – the return has been traumatic and confirmed their worst fears.

The invitation to take part in a dialogue – to converse, discuss, explore – is at the very heart of the exhibition. It is reflected in the organisation of the space; the photographs form the middle section framed at the entry by a textual component detailing the thousand-year history of Jews in Poland, including a section devoted to the present situation in Poland. Visitors are also encouraged to leave reflective comments about the exhibition and their own return journeys. The public programs – over two dozen events scheduled over the duration of the exhibition – have been a critical part of extending the conversation.

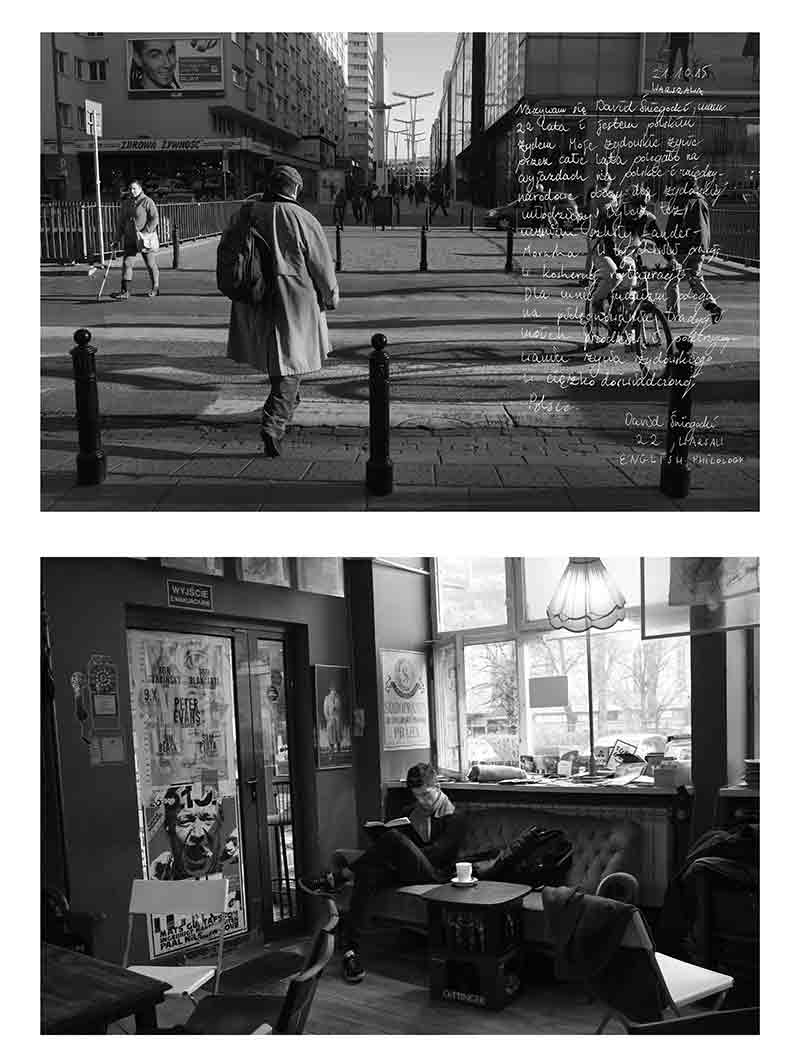

The importance of dialogue underscores Goldbergʼs photographs. Her black and white work focuses on portraits, with a particular emphasis on environment. She uses the form of the diptych, usually a person alongside a photograph of their home, school or town. Traversing the country, she has documented young Poles and Polish Jews, labelling the photos according to the first name of its subjects “Hanna”, “Estera”, “Eliza”, “David” and adding the location such as Warsaw, Krakow, Gdansk, Poznan, Wroclaw, followed by the date. Goldberg invites her subjects to write something in Yiddish or Polish about themselves and their experiences. Their handwriting digitally transposed onto the image adds a diaristic overlay. By allowing her subjects to speak and incorporating their words directly into the works, Goldbergʼs photographs are a powerful expression of young people exploring their Jewish roots and culture. Her works embody the importance of language to not only give shape to the past but also to create a future.