As Paul Virilio once noted, “Art’s most serious drawback is its immediacy, its ability to be perceived at a glance”, countering the shrillness of contemporary art in “its bid to be heard without delay – that is, without necessitating attention, without requiring the onlooker’s prolonged reflection and instead going for the conditioned reflex, for a reactionary and simultaneous activity”.[1] Virilio, in the context of an art of violence, employing sound and image, was arguing for dialogue, against passivity. In the era of mass media, art cannot be aesthetically or ethically silent.[2] We cannot plead ignorance. The exhibition Black White & Restive: Cross-cultural initiatives in Australian Contemporary Art also rallies against silence, establishing a case for dialogue, collaboration, influence and exchange. It addresses the subject of cross-cultural or trans-cultural engagement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists. The viewer cannot perceive it “at a glance”; the art has been produced in an ongoing set of relationships, some two-way, some unequal, dislocated or misjudged in their intentions, so there are bigger issues at stake. Beautiful and alluring as this exhibition is – some of the works glow and arrest with their visual power and are impressively monumental in scale – to attend only to this surface layer is to miss the larger impact of its proposition.

Why “restive”? A quality of impatience in the face of control, authority or restraint, the term also implies an inability to be still, silent or submissive, suggesting that the subject is difficult to control. Thus the exhibition establishes its bona fides from the outset, giving the audience a textured and nuanced palette with which to enter the conversation. And this conversation is an important and sometimes unsettling one. Aiming to continue the dialogue established in the Queensland Art Gallery’s Balance 1990: Views, Visions, Influences exhibition, Black White & Restive refuses a seamless story of successful exchange, instead offering us a place to consider the risks, the stumbling blocks and the opportunities, and to see how 67 artists, black and white, have found ways to talk to each other (or not, in some cases).

The curatorial mission to promote “creative cross-cultural dialogue and expression”[3] was, for curator Una Rey, about enabling everyone to speak without worrying about agreement. Billed as “controversial”, most of the material that might have been problematic is now historical (with perhaps one notable exception[4]). Some of the later work is quite assertive in intent and impact, revealing a confidence in both individuals and collaborations, however tentatively they may have started out. Telling will be the response of audiences across the life of the exhibition and beyond. But it’s about time these issues were re-exposed – tilled, gleaned and re-seeded.

Histories of non-Indigenous appropriation of indigenous art have left a legacy of apprehension or fear when it comes to talk of collaboration between Indigenous and non-indigenous artists. The ongoing colonial legacy, resulting in the loss of land, culture and language, is central to this. Inequalities of power and influence, racism and cultural theft have been writ large on Aboriginal experience in Australia. It is impossible for black and white artists to work together without an understanding of this history, including recent practices in the art market and the panoply of critical receptions of Aboriginal art.

In the accompanying symposium, held the day after the opening of the exhibition (perhaps a little too soon for everyone present to fully comprehend it), there was lively discussion about this trepidation, with particular mention of the blow-up around Imants Tillers’ painting The Nine Shots (1985) in which Tillers appropriated Michael Nelson Jagamarra’s Five Stories (1984) without permission, and instances of Gordon Bennett getting in trouble with “the black police”. Academic Ian McLean ventured that art is a way to start a conversation, that it is a meeting place. Responding to curator Una Rey’s question ”why now?”, he replied that it was an opportunity for difficult conversations. McLean’s comments included the idea that both Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures are multicultural, yet many non-Indigenous people do not see Aboriginal people as cross-cultural. There is also the issue of respect and who has the right to speak. The many and varied urban and regional Indigenous voices need to be heard.

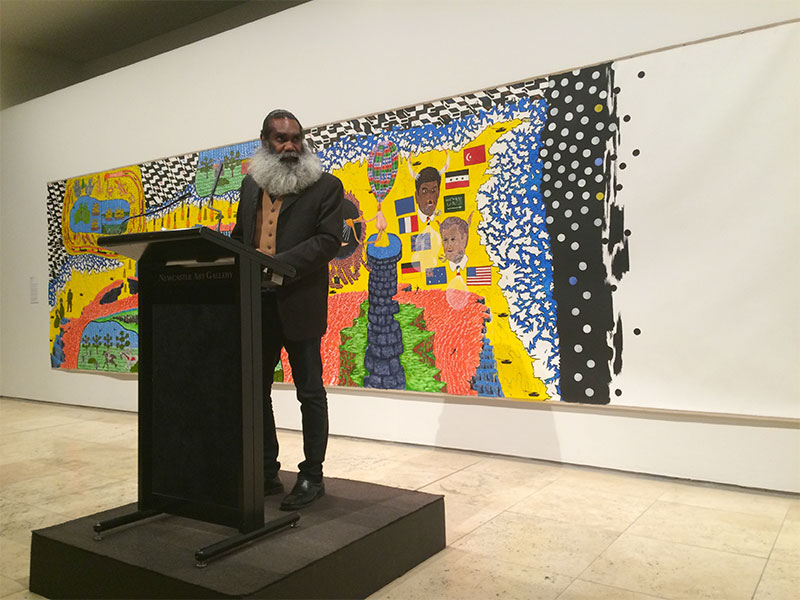

Trevor Jamieson, an award-winning actor of Pitjantjatjara heritage, spoke of his people always being misinterpreted, being portrayed as “less than”. He put it succinctly when he said “First Fleet came over with their own manuscript; we already had one here”.[5] Bandjalung curator Djon Mundine reminded everyone that in the 1980s there was no Aboriginal voice, there were no Aboriginal curators and no Aboriginal filtering system. He noted that early Aboriginal artist collaborations with non-Indigenous artists were one-sided, that a famous white artist would come and work in an unequal way before things shifted to embrace a greater equality. Most significantly, Mundine drew on the idea of relational art – a term with much currency in the discourses of contemporary art, although not usually applied to painting – supporting the fact that people make art to create relationships.

Perth-based filmmaker and descendant of the Bardi and Jabbir-Jabbir peoples Taryne Laffar also commented that in these changing times, when things are often done differently from traditional art and cultural practices, it’s dangerous to start doing things when you don’t have a relationship. Similarly, Gabrielle Sullivan, Manager at Martumili Artists in 2006–15, emphasised the importance of relationships. When working in Indigenous communities, you paint with others alongside you – you have to do it with other people. She said “you’re still in country when you’re painting and you can’t go into country alone”.[6] Painting on your own, as in the Western tradition, is not an option as you wouldn’t have the authority to tell the stories, ownership of country is not individual.

One of the most famous relationships at the core of this exhibition is the friendship and working relationship between Hermannsburg (Ntaria) artist Albert Namatjira and white artist Rex Battarbee. Namatjira’s ancestral narratives painted in Western watercolours, a painting style taught to him by Battarbee, made Namatjira, as Rey describes him, “the foundational figurehead for postcolonial cross-cultural identities in Australia”[7] In return, Battarbee developed a new understanding of Western Arrernte Country.

Daniel Boyd’s poignant painting Untitled (2013) sits alongside Namatjira and Battarbee’s work. The image is sourced from a photograph taken by Rex Battarbee in 1946, and shows Namatjira painting at Standley Chasm in the MacDonnell Ranges, with the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester looking over his shoulders. Now in grey scale and overlaid with dots (the ubiquitous contemporary reference to Aboriginality, the dot matrix of printing technologies and the allover abstraction of high modernist painting), it is a reminder of the perpetual misrepresentations of Albert Namatjira himself, his ultimate fate living between two worlds, and the failure of real cultural exchange. But this failure is not the story of the whole exhibition.

There are majestic examples of successful collaborations and/or dialogues that soar and sing here. Yarrkalpa (Hunting Ground) Scale 1:2500 (or thereabouts) (2013) is a five-metre wide painting by eight Martu women artists working collaboratively on this one image of Country. To create an immersive experience, these senior desert artists invited Sydney-based Lynette Wallworth to come to their country and work on a film of them painting. As they work, the 45-minute film Always Walking Country is interspersed with satellite images, film of fires and country, and a soundtrack that includes New York-based Antony (now Anohni) singing a quiet, calling response. The film is projected onto three wall-sized screens in a u-shape arrangement and, in the darkened space, presents a haunting and evocative experience.

There are relationships across the exhibition spaces (which take up the whole two floors of the Newcastle Art Gallery) and these create dialogues of their own, sometimes allowing us to re-experience in material terms the now-historical conceptual debates that occurred in the artworld. One of the most prominent of these is the display of Michael Nelson Jagamarra’s Untitled (1989) with Imants Tillers’ White Aborigines (No. 2) (1983); their proximity recalls Tillers’ Nine Shots (1985) (not included in the show) appropriating magazine images of Michael Nelson Jagamarra’s Five Stories (a work incorporating Wanampi, the rainbow serpent) from 1984, and Georg Baselitz’s Forward Wind (1966), without permission from either artist – an action which created significant controversy at the time.

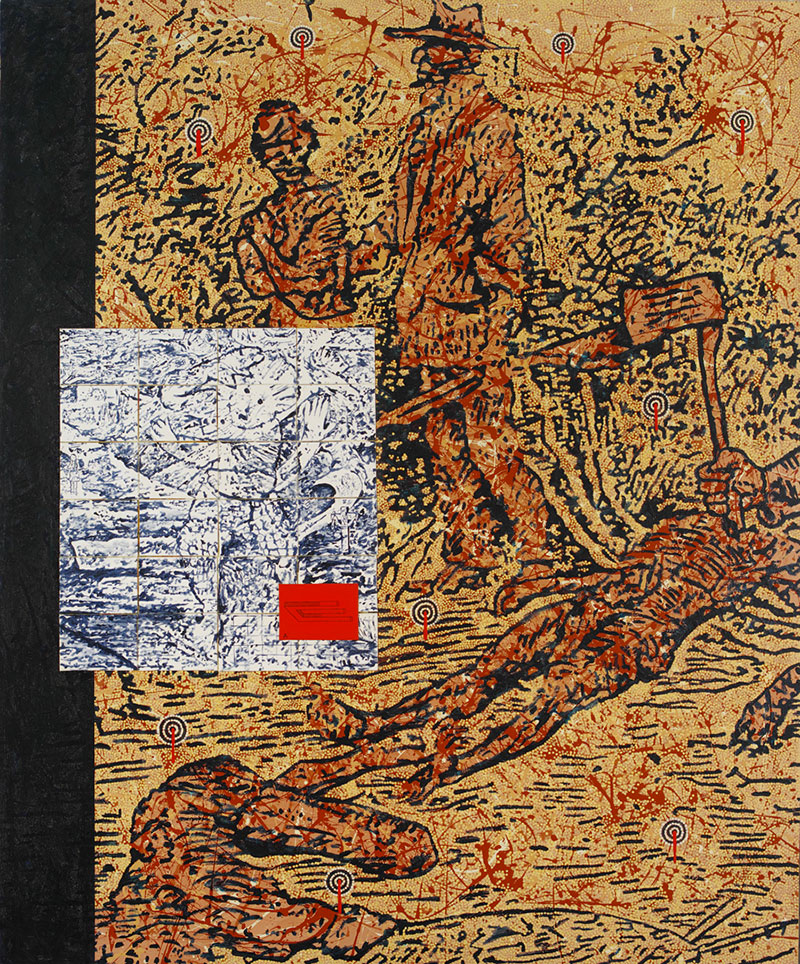

There were stinging attacks on Tillers for his “theft” of the image, and there were serious ramifications for Jagamarra, because he was entrusted with these stories and his duty was to look after and protect them. Untitled and White Aborigines now hang near Fatherland (2008), one of the collaborative works between Tillers and Michael Nelson Jagamarra done after this clash as a way to ameliorate their grievances. Added to the mix is the inclusion on the opposite wall of Gordon Bennett’s The Nine Ricochets (Fall Down Black Fella, Jump Up White Fella (1990). Here Bennett picks up the conversation by borrowing Tillers’ work White Aborigines (No. 2), a work which contains no Aboriginal imagery and was in fact about the complexities of his Latvian–Australian identity. It is no coincidence that the work’s title also parodies Tillers’ Nine Shots.

Bennett’s work is about the violence of colonisation, a point reinforced by the dialogue of “borrowings” from the work of non-Indigenous artists. While many of the works shown come from the Newcastle Art Gallery collection (revealing the strengths of the collection) Nine Shots is certainly the ghost in the room.

Another important inclusion here is a work called Ricochets, Manifest Destiny (A Painting for the Distant Future: 2001?), Window Onto a Shadow Universe (1993), made up of a series of fax exchanges between Bennett and Tillers, with photographs and canvas boards, not seen since 1993, but uncovered in Bennett’s personal archive during research for Black White & Restive. Revealing some of the issues between them and the tentative efforts to negotiate some form of rapprochement and potential collaboration, they present a rare insight.

There is much contained in this exhibition that is worthy of recognition. Two Laws One Big Spirit is essentially an exhibition unto itself. A series of paintings done by Rusty Peters and Peter Adsett over fourteen days, each working independently, but effectively side-by-side, Peters portrays his own country, and spiritual connection, while Adsett explores Western models of abstraction. A conversation, more than a collaboration, the works sit beside each other in a dialogue that is as much about the language of painting as it is about the role of the artist.

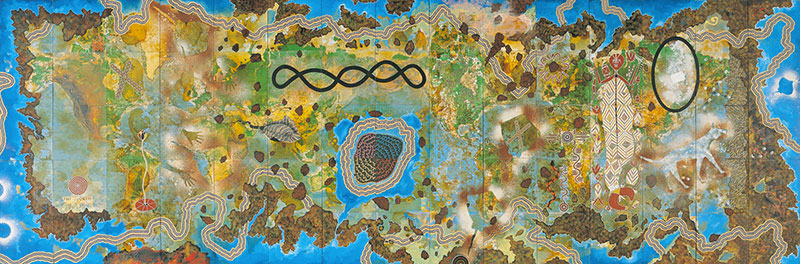

Michael Eather and Friends (thirteen artists from across Australia, including Ruby Napangardi and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri) created Two Worlds in 1995–97, a work created on 75 boards and brought together at the end of the process. This monumental installation, measuring 300 x 956 cm, presents two topographic global maps overlaid with both traditional and personal symbols, to provide a testament to the negotiation between cultures, and the nature of transition and dislocation. A ghost dog represents Lin Onus, who had passed away before the work was completed.

Margaret Preston’s work, from the gallery’s own collection is included, as is a vignette of works by Preston, Lucas Grogan – who notoriously and provocatively appropriated Western Arnhem Land styles in his work, resulting in an extremely negative backlash – and Namatjira, represented here with a painted boomerang, an item dismissed by critics and associated with “tourist art”. Moving between styles and forms is not as innocent as we might like to think.

In other works, as just brief mentions, Tracey Moffat’s Other DVD (2009) plays with the cinematic language of the exotic and the primitive, in ironic dialogue with the entire Western tradition; there is homage to the ongoing collaboration between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal printmakers; photographic work by Nici Cumpston that evokes the sentient nature of country; a parallel play between Tony Tuckson’s abstraction and that of Gordon Bennett, each drawing on the traditions of the other culture; and works by artists such as Tim Johnson, Vernon Ah Kee (holding people to account with his work Tolerance, 2005), Trevor Nicholls and Danie Mellor (whose glazed earthenware boomerangs recall Namatjira’s 1950s wooden exemplar – defiant in rejecting the appellation of ‘’souvenir”).

Black White & Restive does not deliver an easy answer to the problem of how to conduct a “proper” engagement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists and art practices. Instead, it delivers a sortie into the sporadic campaign, which Margo Neale observes produces “fields of disturbance” (a proposition of Canadian artist David Garneau).[8] Blessedly open-ended, it engages with ideas and dilemmas, delivering honest insights into the cross-cultural landscape.

Footnotes

- ^ Paul Virilio (trans. Julie Rose), ‘Silence on Trial’ in Art and Fear, Continuum: London and New York, 2000, pp. 45–6.

- ^ John Armitage, Ibid, Intro. p. 7.

- ^ Liz Burcham, ‘Foreword’ in Black White & Restive, exhibition catalogue, Newcastle Art Gallery, 2016, p. 5.

- ^ A work by Lucas Grogan, from 2008, The Boys and I Were Swallowed By a Bunyip, was included as a salutary reminder of the dangers of naïve borrowing. Having recently completed his studies, the young Grogan foolishly appropriated Aboriginal styles into his own work with a very specific meaning about sex, gay life and the rejection of social mores. In the absence of any Indigenous voice, and broadcast widely across the Internet , the result was a huge hostility to Grogan and several artists withdrew from shows in which he was to participate. In Black White & Restive, it serves as a kind of postscript, tucked into a corner – a moral tale of what happens when you don’t have proper relationships with the owners of such material or any authority to use it.

- ^ From notes taken by the author during the symposium discussion, 28 May 2016.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Una Rey, Black White and Restive, exhibition catalogue, Newcastle Art Gallery, 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Margo Neale, ‘Collaboration, Disturbance and Collective Dreams: Two Worlds: Michael Eather and Friends’ in Black White & Restive, exhibition catalogue, Newcastle Art Gallery, 2016, pp. 51, 57.