I feel in myself a soul as immense as the world, truly a soul as deep as the deepest of rivers, my chest has the power to expand without limit.

Frantz Fanon, The Fact of Blackness (1952).

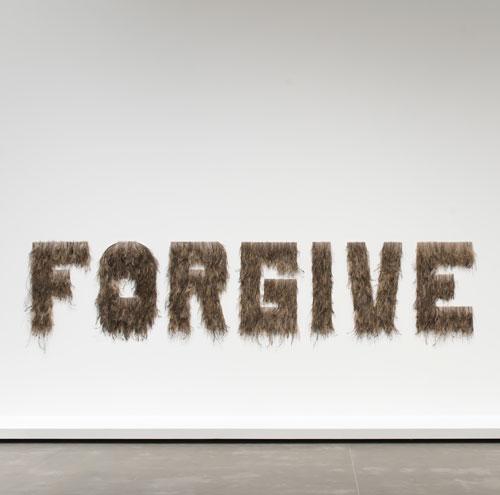

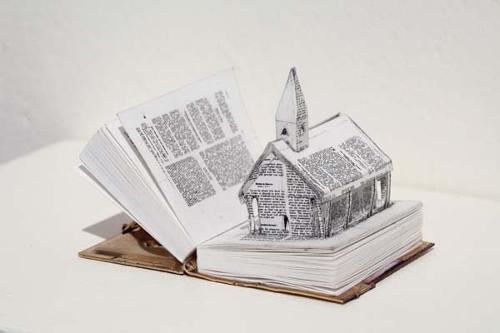

Reclamation - the act of reclaiming or taking back something which one once possessed but has since been deprived of – is itself an act of self-determination. In one way the work in the recent exhibition ®eclaimed, much of it produced in the last four years, reclaims the political ground taken by conservative forces in the Howard era. Almost two decades ago Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures enjoyed a brief moment in the sun in the aftermath of the High Court's decision in the Mabo case; the then Prime Minister Paul Keating pleaded for greater understanding and for the rest of the population to see the decision not as a threat but as a moment of transformation where we could reckon with the ghosts that haunt the national psyche. Sadly, we never reached that moment of reckoning.

For much of the next decade Keating was derided as a traitorous bleeding heart and his appeal to the nation’s conscience was recast by those same conservative forces as a 'black armband’ version of Australian history. In a strategic rhetorical manoeuvre, the straightforward notion of reconciliation was bifurcated into symbolic and practical forms and the language of the political discourse subtly moved to restore Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to the same margins as before. Labor would not be returned for 11 years and even then it was something of a freak event; the cult of personality that was Kevin 07 was a mere glitch in the electoral cycle.

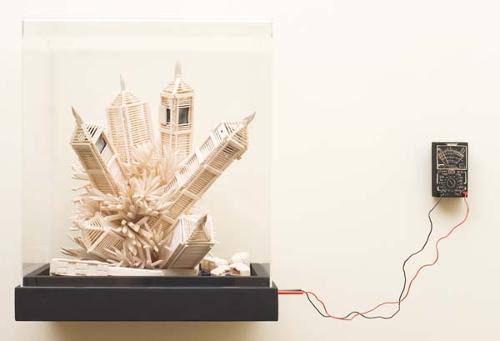

I recently heard Anthony Gardner, an expatriate living and working in the United Kingdom and currently a visiting scholar at the Courtauld Institute, describe the state of exclusion that exists overseas towards art from Australia as a kind of ‘tyrannical apathy’ practised slavishly by self-obsessed North Atlantic cognoscenti. In global dialogue, art from Australia – Australian art – is still a victim of reductive tropes of ‘Australia’; a kind of cultural imperialism that conflates the "North Atlantic" with the “global”. In my mind I began to speculate about the radical apathy that might describe the discursive gap that exists between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the rest of the Australian population. Certainly, it might be said that despite our shared history we experience the idea of ‘Australia’ differently.

Another expatriate, the journalist John Pilger, recently described the way in which the Murdoch media represents Aboriginal people. As Rupert’s empire teetered the streets of London filled with the marginalised, disaffected and bored. Pilger reckons it is “not unsympathetic” in its representation of Aboriginal people but by and large it conforms to a racist trope. In this way of thinking Aboriginal people are “perennial victims of each other”; a rhetorical device that is a quick way to absolution. Truth and the brute facts of history evaporate in a sedative haze of denialism. The political and media debate around the weeks before the Howard government enacted its Northern Territory Emergency Response, during which a catalogue of Grand Guignol horror was daily recited on the television news, fits almost too neatly into this way of thinking.

This way of thinking holds that Aboriginal people themselves are to blame for their generational poverty and the social dysfunction that affects their communities, their suffering belongs to them, and from the relative safety of this position you could extrapolate that they are to blame for everything. The hereditary original sin – dispossession and the theft of the Australian land mass – is rarely if ever confronted and the barely suppressed rage of Aboriginal people is pathologised as a form of sociopathy. Let’s make this clear: Aboriginal people are entitled to feel deprived. Only the utterly delusional could suggest otherwise. But instead the popular, media and political discourse that constellates around the term ‘Aboriginal’ inheres a radical amnesia or collective delusion, if you like. In fact, if you don’t believe in it, the discourse doesn’t make sense.

Latterly, Gary Johns – a former junior minister in the Keating government – has continued the ideological attack, largely in the Murdoch press, describing Aboriginal culture as a quintessentially primitive way of life that condemned our people to lives that were inevitably “brutish” and “short”. Well, for some of us, not much has changed. An attempt at shortening the public life of one Aboriginal intellectual played out recently; at the same time as she brought legal proceedings against a News Limited journalist for his deeply hurtful remarks about her identity as an Aboriginal person. As Richard Bell’s canvas says, kick somebody else.

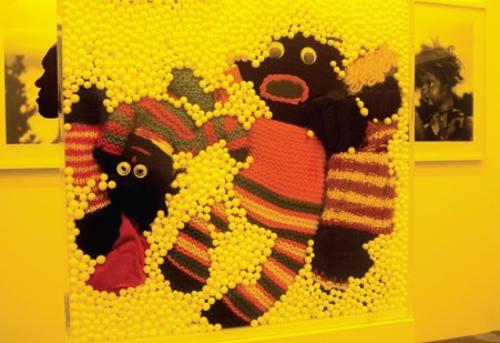

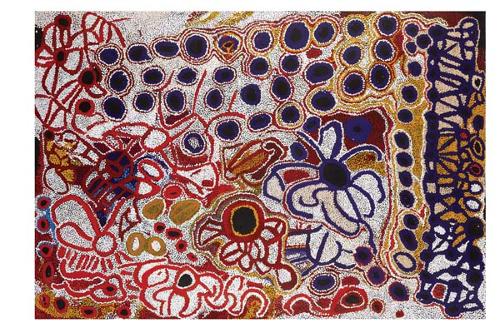

Bell’s Scratch An Aussie (2008) series riffs on Bell’s Theorem which is actually now more of a manifesto; not simply that “Aboriginal art is a white thing” but that Australian (and Western) art does not exist – among other inconvenient truths and provocations – “pay the rent”, “I am and I am not”, “I am not sorry”. In another work from the same series It happens to white folks too (2008) Bell answers the media hyperbole around Aboriginal family and domestic violence. A 60s comic strip woman wears a bruise; a man in the extreme foreground thinks to himself or says out aloud to his victim “I’m afraid to fight another man coz he might beat me up”. Bell’s paintings are a lightning rod. They stir people up and clear the air; at least temporarily. When racism is inverted, and performed in a deliberate act of mimicry against rather than by the ethnic majority, it can produce startling effects. For instance, when Bell famously wore a t-shirt suggesting that white girls were poor sexual partners, there was hysterical outrage. So much so, that the object lesson was missed. The provocation is to imagine for a moment how it might feel to be subjected to racism on a daily basis, knowing how bad it can make you feel in an instant.

I believe that nothing has ever happened without it being imagined first. I believe that we Aboriginal people need to imagine victory before we can actually get it. And to get there, we have to ask ourselves “what are we fighting for?”

Richard Bell, 2010

(An excerpt from the catalogue essay for ®eclaimed, an exhibition of contemporary Australian art, held at the Bathurst Regional Art Gallery from 7 October to 20 November 2011.)