Art & Medicine

Issue 17:2 | June 1997

This issue responds to how the discourses of art and medicine intersect to explore the new frontiers of the body aided by new imaging technologies and art in hospitals. It examines the role of art in reconstructive, therapeutic, healing and enabling strategies as artists tackle medical ethics and practices head on

In this issue

The Visible Human Project: Life and death in cyberspace

Art Therapy: The New Frontier

Looks at the program in the College of Fine Art at the University of New South Wales.

Artworks in the New Children's Hospital Westmead NSW

The new building was conceived with the idea that artworks would be included throughout the new hospital as part of the desire to create a total healing environment. Since 1995 when the first patients were admitted the collection has continued to grow. An illustrated catalogue of the collection has also been published.

Body Suits

Body suits, conceived by Jane Trengove of Arts Access Victoria, proposes the body as a site for investigation with the contributing artists being mostly people who experience 'bodily difference due to disability'. Touring show in 1997.

Drugs 'n' Art

The role of drugs and art making is examined in the works of particular artists. Historically drugs have been used for enlightenment as well as for healing or endurance....

Getting Better all the Time: Austin and Repatriation Medical Centre Arts Program

The Austin and Repatriation Medical Centre (Victoria) has an innovative arts program. Commenced in 1989 and now holds an annual exhibition of sculpture.

Hand and Eye: The Art of Michael Esson

Michael Esson is fascinated by medical science. His work is not simply a satire of the medical profession or a reflection of the limitations of modern science. The surgeon is a metaphor for the mind facing the limits of its own ability to look into the darkness of nature.

Healing Places: The Art of Placemaking in Health Facilities

Examines ideas of place in medical/health facilities from different perspectives. What role does art play in these places? To promote wellness, designers need to create environments that help in reducing stress. Art has an important role to play in helping people to heal.

Image Bank for Art and the Body - Medical Imaging

Medical imaging through the work of nine artists: James Guppy, Ruth Waller, Victor Dellavia, Elizabeth Abbott, Julie Rrap, Jan Parker, Tina Gonsalves, Kate Campbell-Pope and Claire Bailey. Artists statements and colour images included.

Introspecting

"The belief system that makes the artworld so unlike - let us say - the builder's hardware world is distinguished primarily by the doctrines that there are no truths and that nothing is real.... To put the point with moderation: artists would not be inconvenienced in the least by a general theory of representation that brought the trustworthiness of their critic somewhere within powerful cooee of the trustworthiness of their radiologist. And Theory owes it to them."

Kevin Todd: Magnetic resonance

Linking Art, Science and Technology through the body

Looks at the conference 'inter sections 1996' hosted by the College of Fine Arts at the University of New South Wales. The theme for the conference was Imag(in)ing Bodies; Issues of art, design, technolgy, health, medicine and science.

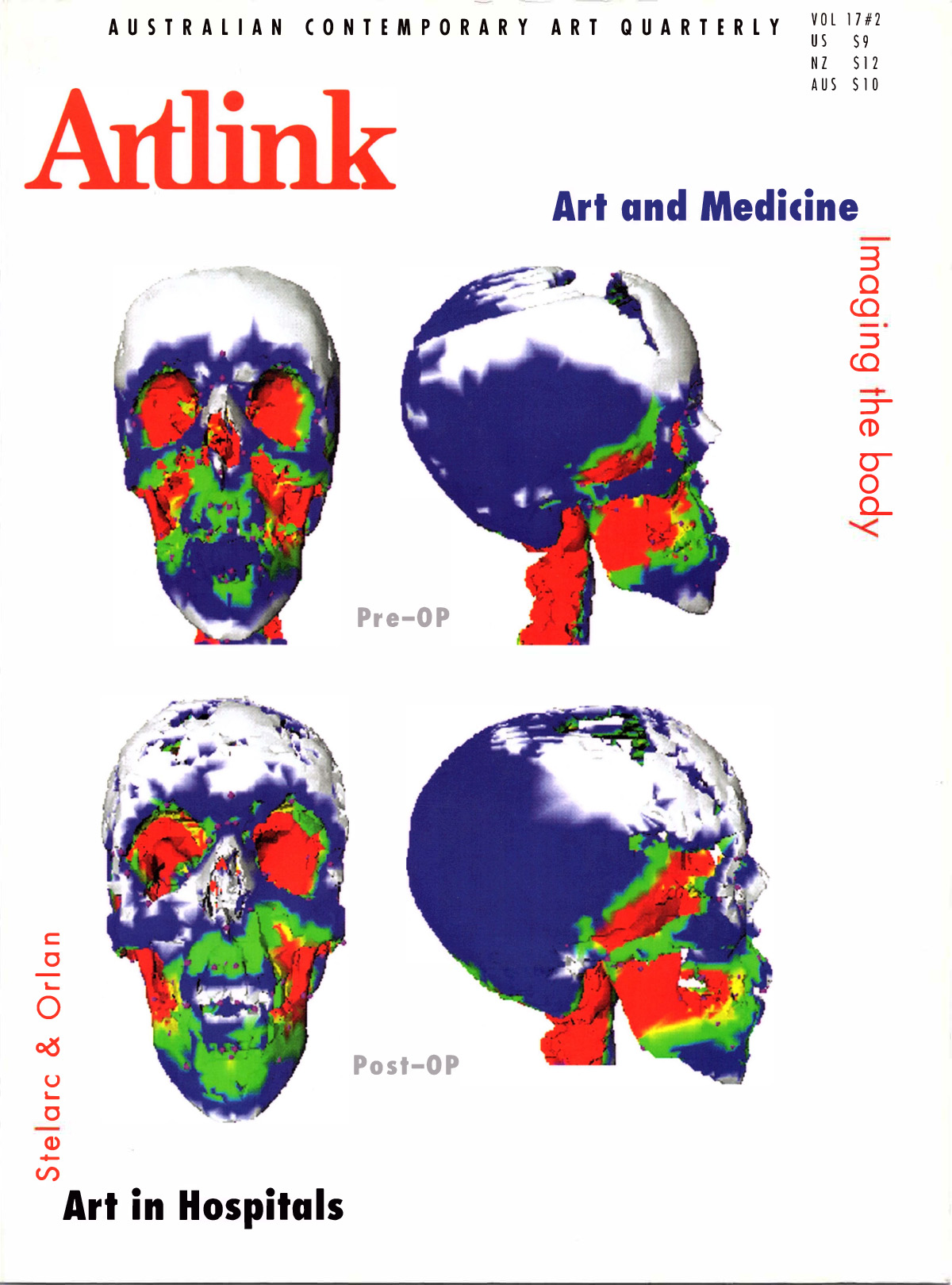

Manifesto of Carnal Art

Carnal art is self portraiture in the classical sense, but realised through the possibility of technology. It swings between defiguration and refiguration. Its inscription in the flesh is a function of our age. The body has become a 'modified ready-made', no longer seen as the ideal it once represented.

Means to an Endoscope: Art, Medicine and the Body

Art medicine and the body was a project spanning 18 months. There were 28 participating artists. The exhibition opened at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art in August 1996 followed by the performance and forum.

Post-mortem: Farrell and Parkin

For a number of years the collaboration of Farrell and Parkin has produced photographic imagery dealing with medical history. Their photographic work involves the almost archaeological reconstruction of medical contraptions together with bandaging and stirrups and so on which are described in medical texts.

The Faulding Collection

Looks at the art collecting practice of international pharmaceutical and healthcare company F.H.Faulding & Co.

The Irrepressible Imprecision of Emotion

One of the general aims of internationally focussed survey exhibitions is to reflect the art of a particular time....However there is also a sense in which exhibitions of this nature can tend to operate as a form of cultural engineering, where the very status of inclusion in such exhibitions influences the kind of work made.

Whose Body? Ethics and Experiment in Art

How does the notion of experiment translate from the realms of scientific medicine to the realms of art? We are forced to examine how legal and ethical liabilities of behaviour are encoded. Looks at the work of Stelarc and Orlan.

Youth Arts in Hospital

The Youth Arts program at the Department of Adolescent Medicine at the New Children's Hospital Sydney commenced in 1984. In 1994 the project 'Art Injection' took place resulting in a book.

A Manifesto of Arrival and Understanding

Exhibition review Paintings: Zhong Chen

Adelaide Central Gallery,

South Australia

7 March - 20 April 1997

An Elliptical Traverse

Exhibition review Inside the visible - Alternative views of 20th Century Art through Women's Eyes

Art Gallery of Western Australia

13 February - 6 April 1997

Compelling Viewing

Exhibition review In focus: Rover Thomas

Stories: Works from the Holmes a Court Collection

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

The University of Western Australia

Part of the 1997 Festival of Perth

Getting a Glimpse of the San

Exhibition review Eland and Moon: Contemporary San Art of Southern Africa

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

29 November - 31 March 1997

Hello Sailor

Exhibition review Sculpture Bert Flugelman

Greenaway Art Gallery,

Adelaide, South Australia

23 April - 18 May 1997

Historical Incisions

Exhibition Review Intervention 4: Michael Schlitz

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

3 February - 2 March 1997

Salome's Dance

Exhibition review Blind: Annette Bezor

Greenaway Art Gallery,

Adelaide, South Australia

March 26 - April 20 1997

Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire

Book review Letters and Liars: Norman Lindsay and the Lindsay Family by Joanna Mendelssohn

Angus and Robertson

RRP $19.95

Search and You Shall Find

Book review Max Germaine's Artists and Galleries on CD Rom

Published by Macquarie Multimedia

RRP $199

(reviewed by Anna Ward with Julia Farrow vi$copy@wr.com.au)