'My eye!' is a term once used as an exclamation of astonishment and what an eyeful there was at the wonderfully titled 'Eyes Lies and Illusions', an exhibition held at Melbourne's ACMI in Federation Square late last year. This exhibition displayed over 500 optical inventions and illusion-making gadgets from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century. Drawn largely from a private collection owned by German experimental filmmaker Werner Nekes the exhibition, (which was originally developed for the Hayward Gallery in London), also featured works by local and international contemporary artists whose works explore aspects of visual illusionism.

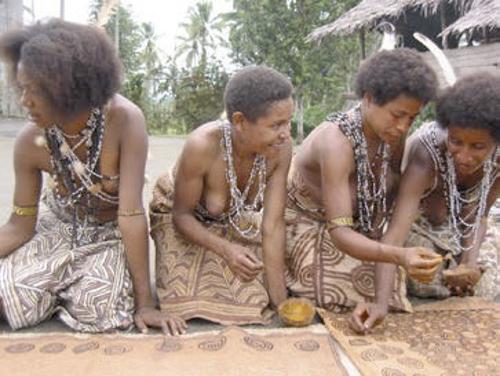

The journey began following the development of the pre-cinematic visual technology with exquisitely detailed shadow puppets from Indonesia, transparent hand-coloured puppets from South Asia and the first magic lanterns made in China. These lanterns were something to behold, fat-bellied long-bearded men at once both genie and bottle - almost alive with the promise of magic they would have once conjured up for their medieval audiences. Moving westwards and forward in time the apparatuses themselves were as much a source of fascination and wonder as the illusions they created. Hand-coloured lithographic paper dioramas six layers deep were displayed both within and outside of their made-to-measure black wooden box, cut-out paper layers piled neatly flat on a table resembled a three-dimensional postcard.

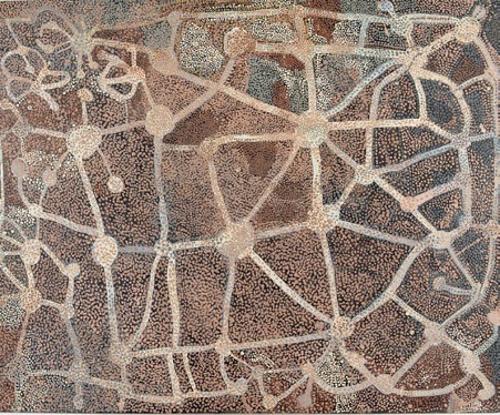

Puzzle pictures, anamorphic images, paper animations, illuminated drawings, geometric optical abstractions from the eighteenth century, each object on display marked a new discovery that was then incorporated into the lives of people of that time. Developments in science, technology, philosophy and the humanities were traced as subject matter over time, shifted from devilish apparitions and magical creatures to recreating real places and events. Illuminated disasters, images of fire and flood were some of the more interesting attempts at bringing the world into the lounge-rooms of the middle classes of yesteryear, a fascination that continues today with the graphic depictions of tragedy beamed onto our television sets as the nightly news.

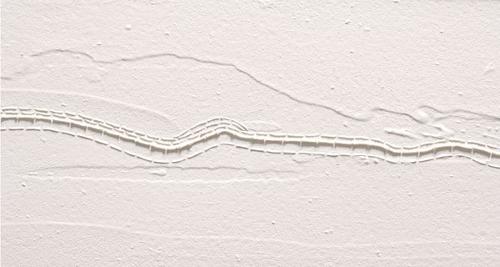

Something that struck me as I was walking through the exhibition was how physical the act of 'looking' at the displays became. Viewers had to manoeuver themselves into correct viewing positions, twist to see something from another angle, focus and unfocus their eyes... one became aware that the simple act of looking is not a passive activity and that perception is something that happens in the brain rather than in front of one's eyes. The creators of these objects understood that under the right conditions, the human brain will smooth over gaps to create something whole out of parts, will struggle to make sense out of senselessness. Modern illusions too often tend to be presented to us as complete images. There is nothing really left for our brains to do but passively 'watch'. Today's technologies smooth over perceptual gaps for us and the twenty-first century viewer could be accused of, to borrow another old saying, 'seeing with only half an eye'.

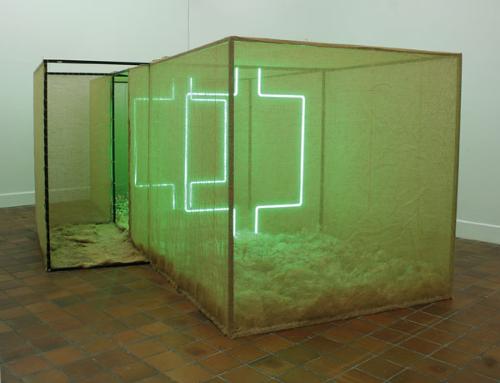

The most interesting of the pieces by contemporary artists made the viewers work for their perceptual bang. German artist Alfons Schilling's work 'Gazelle' literally turned our perceptual experience inside out. A viewing device made out of prisms and mirrors and mounted on an easel inverted the normal spatial relations of whatever was seen through it. Objects sitting on a carpet become negative holes in a carpet seen in relief. To look through this device was to experience a world governed by completely different laws regulating time and space.

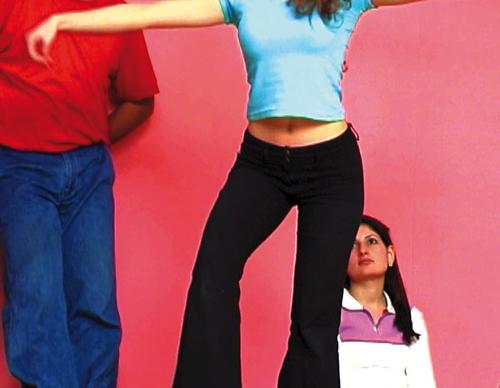

Sydney duo David Lawley and Jaki Middleton's 'The sound before you make it' brought hundreds of three-dimensional plastic dancing zombies to life. Based on a nineteeth century zoetrope, a spinning device used to created simple animations, Lawley's and Middleton's dancers giddily grooved to what sounded very much like 'Thriller', Wacko Jacko's hit of the 80's, perhaps a sly reference to the once cutting edge video technologies that were Jackson's trademark at that time.