Ask six people what 'savvy' means and you might get six answers – 'cool', 'hip', 'funky', 'shrewd', 'street smart' for starters. Even 'Get it?', though that requires a question mark, and maybe an older generation.

In Savvy: New Australian Art, curator Alison Kubler has assembled six, mostly young, artists three of whom are from Queensland (Beata Batorowicz, Christopher Bennie, Mandana Mapar) and one each from New South Wales (Lionel Bawden, Nicola Brown) and Victoria (Sangeeta Sandrasegar).

Apart from their 'savvy approaches to art', Kubler argues in her catalogue essay that these artists 'all place emphasis on the importance of technique, process and attention to detail in the creation of provocative new work'. Kubler notes that they present 'a hands-on approach to art production, ultimately defying contemporary trends for an immediate quick-art fix'.

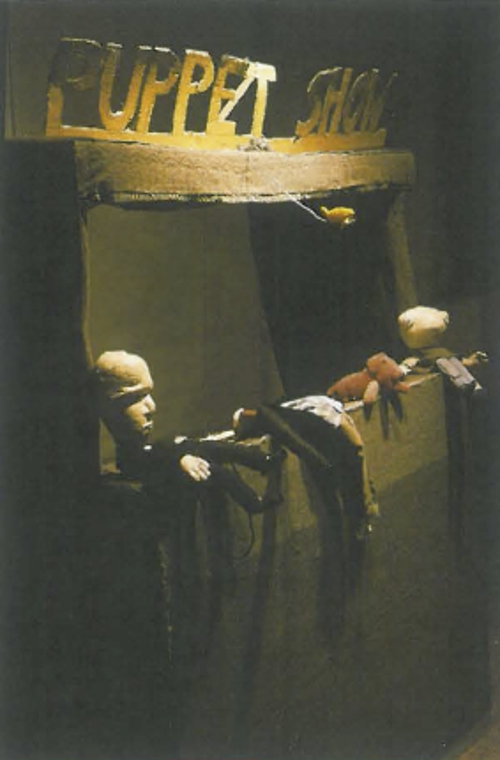

The first work encountered might well derail this claim. In Bennie's DVD The Mothership, the artist performs a solitary dance, seemingly oblivious of the camera. His performance is nondescript, in an inane Bruce Nauman-type way. The adult son dances to a seemingly endless techno rhythm in his mother's living room. This cramped domestic sphere, with its glass ornaments, gold-framed print and floral lounge, provides an incongruous setting, just as this repeated soundtrack provides an incongruous background for the whole exhibition. In an adjacent space, Bennie continues the play with schmalz, displaying in The sound of love five limited-edition CDs, each of which comprise a mix of two old-styled LPs, the original covers displayed on the wall opposite. The mix of John Denver's Greatest Hits with The delightful Nana Mouskouri remains – perhaps fortunately – a conceptual tease.

If Bennie's The Mothership does look somewhat like a 'quick-art fix', it succeeds in highlighting the performative nature of many of the works in Savvy. And it is a work that lingers in the mind.

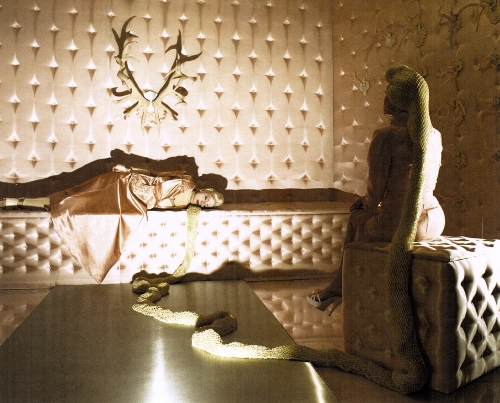

Confirming the performative undercurrent, Batorowicz inhabits the costume and remnants associated with significant male artists, such as Joseph Beuys. Here she is photographed wearing her daughter hood – displayed in the exhibition – from her 'little red riding hood up to no good' series. Such a post-feminist perspective, Kubler argues, returns the artist as a somewhat wilful 'daughter' to her art-historical forebears. Maybe it is the feminine touch, but Batorowicz's hand-crafted red cloak with fox head and other soft-sculpture items suggests a design-led-alternative to recent art history and smacks of art-school theory. Kubler has spatially highlighted the work of Batorowicz in Savvy, but her potential needs further testing.

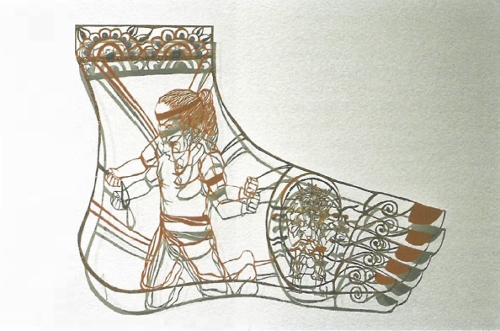

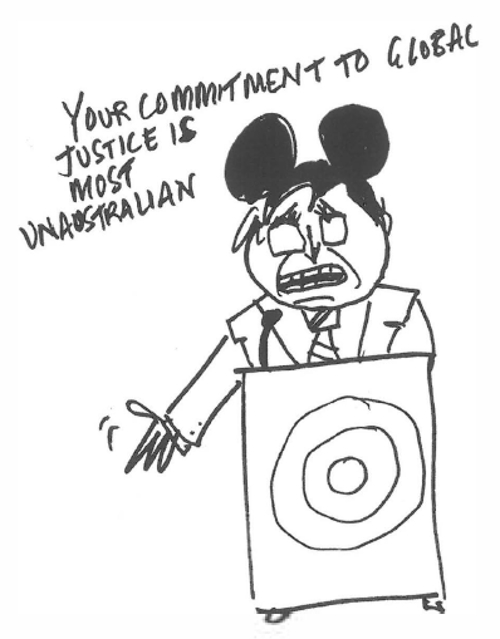

Performance takes on different guises and some political bite in the work of Mapar, Brown and Sandrasegar. The fragile cut-out figures of Sandrasegar float out from the wall like cartoon-strip characters or shadow puppets, their shadows replicating their provocative posture. They could well step out of Japanese Manga comics, though these naked figures bear 'countries' as if badges or, on occasion, pubic hair. Identifying the countries becomes part of the puzzle. A kneeling girl wearing the geographic outline of Australia prostrates herself before a sexually aggressive USA – Australia being fucked over by America no doubt. Not all her funky erotic characters, with their circular 3D heads, are this explicit.

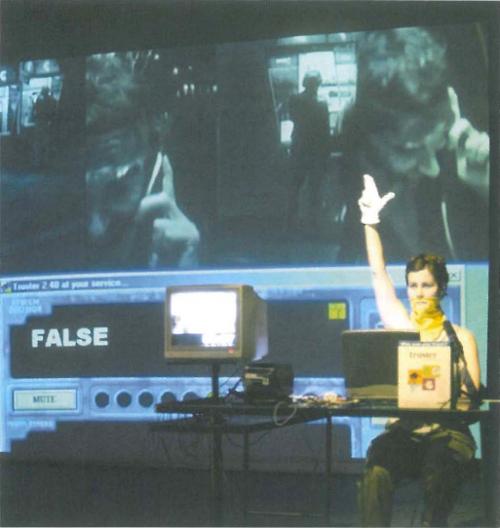

The Iranian-born Mapar produces photographs of herself wearing traditional veils (roosaree) or full-length chador as she writes with light, in Farsi, words such as 'I am not you' or 'Revolutionary'. Her 'sunset storm images', of tropical storm clouds in southern Queensland, stand in for what previous generations have called 'the coming storm' – the threat and unease of global disquiet. Similarly, Brown steps back from direct depictions of militaristic conflict by drawing on images from another era. Here her gentle drawings of military figures are displayed behind several toy-like, small-scaled tableaux of military manoeuvres. The drawings, unframed and finely executed in pencil, offer reminders of Eugene Carchesio's unheroic drawings of headless angels, though they lack that artist's careless touch. Brown's insertion of her features provides a very obvious gender comment on military history and conflict. Her Doll and medal, combining a carefully drawn old-fashioned doll and military medal, gains eloquence in its subtlety.

Bawden's works, Untitled (the monsters), perform like strange 3D-animation stills. Bawden, indeed, takes his point of departure from Stanislaw Lem's 1961 novel Solaris, and particularly the fictional planet of that name whose ocean conjured monsters of the Unconscious. These works are absolutely 'hands-on', being constructed from hundreds of Staedtler coloured pencils and modelled so that at first glance each piece looks like fossilised wood, gleaming with jem-like fissures of brilliant colour. The trick of their manufacture is transcended so that they sit like mysterious museum exhibits – sinuous morphing beings – on their Perspex shelving units.

Savvy may not be an exhibition that delivers a knock-out punch, but Kubler has assembled a group of artists whose future performance will be well worth watching.