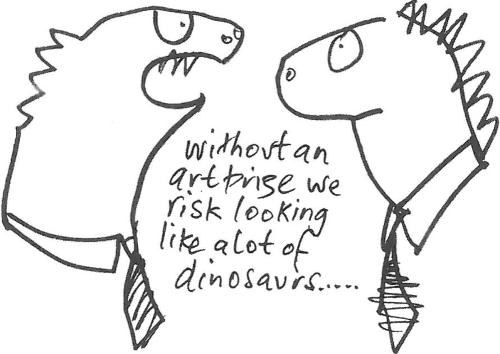

Neville Weston, art critic, artist and keynote speaker at this event convened by the SA School of Art (SASA), spoke about how language is applied in drawing instruction. Weston observed that while 'draw the vase' is a common request, asking someone to 'write the vase' or 'talk the vase' isn't. In the changeover between these verbal, written and visual requests, the word 'about' is lost. It is with this loss that the expectation of something conventional and perhaps unreachable creeps in.

That in mind, writing 'about' drawing should prove an achievable task, but this still isn't so. Any summary of drawing styles or systems soon become limitless lists and the reasons for the conference name, is made clear. Drawing is Everything is perhaps the only truism that can be applied to this core practice and was the only theme in the eclectic mix of lectures, debates, addresses, workshops (for adults and children), artist's talks, performances and exhibitions that broached three drawing areas: education, culture and practice.

While the conference considered drawing theory, the accompanying exhibition sites bore the practical marks of our immense drawing ancestry. Drawing began, as Weston claimed, the first time we held liquid ochre in our mouths, destined for rock walls. After a long and varied lineage, drawing now can be seen as both a culmination and rejection of developments throughout history.

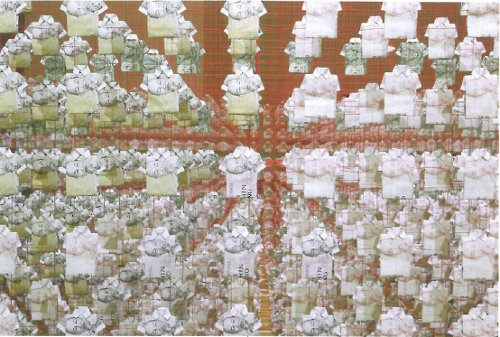

These genealogical extremes were most evident in works by SASA lecturers in Dialecticaline at Prospect Gallery, ranging from Paul Hoban's interest in prehistoric drawings to the wholly digitally works from Margie Kenny. Though ages apart, Hoban and Kenny's works were linked by the incorporation of drawing machines: Hoban's a homemade brush-holding device (which he calls a 'crude machine'), Kenny's a high-tech computer. Removing evidence of the artist's hand, these devices are alternatives to the recent comeback of the handcrafted and handmade. Helen Nieuwendijk constructed her base using a sewing machine upon machine-made paint samples, but still incorporates the irregular and sketchy elements of the hand drawn with woven attachments. These works, where images of children at play contrast with designer paint trends, speak of a space between unconscious drawing and drawing bound by systems.

At Adelaide Central Gallery2 Drawing is a Verb featured works by conference presenters. Johnnie Dady's Battery, a drawing as a noun but previously a verb, had the possibility of millions of drawings in one. A large dark square made by the repetitious markings of biros on heavy paper was glossy and textural, acting as a safety blanket to any expressive lines within. Contained in a square, the drawn marks of Battery were made unfathomable by the sheer number of them.

The SASA Gallery exhibited the daily diary-type thoughts of Ruth Hadlow as they increasingly spread over the gallery walls in Patternbook. Written in either English or Indonesian (the latter chanced a more secretive disclosure in Australia compared to the artist's home in Indonesia), Hadlow pinned red cursive cotton words to the wall or mapped out small patterns of written text. The cross-shaped patterns gradually coalesced into images and became as significant for their negative space pattern as their positive.

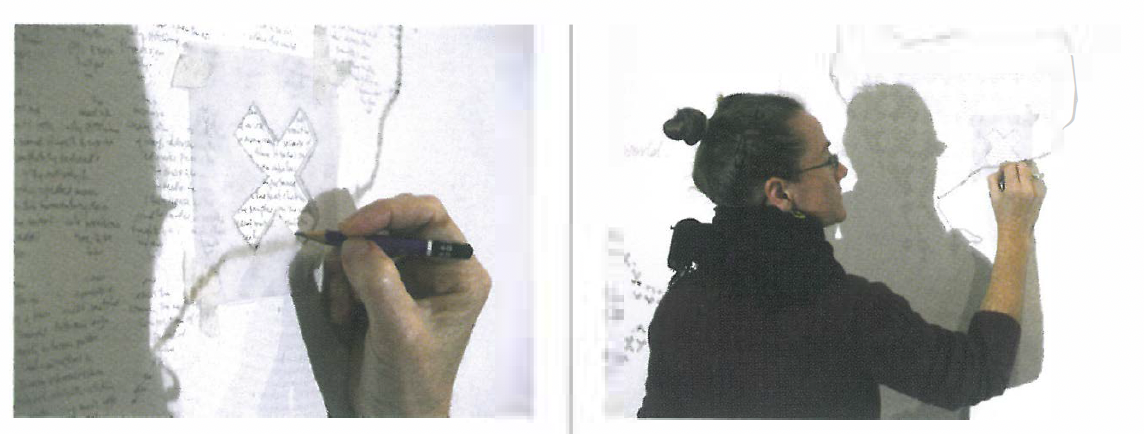

In addition SASA was the site of the Personal Space/Safety Zone 8 drawing performance by Gosia Wlodarczak and Make Your Mark, an exhibition of several of the school's Visual Art drawing students. Meg Wilson's undecipherable sewn and quilted sketches took drawing beyond the pencil and paper, although retaining an almost standard A5 size. Paper remains were entangled in the cotton and allowed the process from which these pieces were derived to become visible.

Drawing, as explored by Neville Weston in his keynote address and through these main exhibitions, is 'about' everything. This conference, as well as the recent opening of drawing-dedicated museums, schools and exhibitions across the world marks a reemergence and refashioning of drawing. It is back even though it has never left.