This was the last in a series of four exhibitions collectively titled Re-positioning Photography, organised by the Queensland Centre for Photography between May and October 2005. Each thematic exhibition presented ways in which contemporary artists have tested the nature of photography. The first three shows took an incisive look at ideological and technical aspects of the medium, but Space Between Words was more understated Jo Grant's curatorial rationale aimed at focussing on properties of photography that are easily overlooked yet can define it most distinctly as an art form. She chose the work of five photographers from different parts of Australia.

Courtney Petersen's essay in the accompanying brochure alluded to the idea of a picture being worth a thousand words, and suggested that what really matters are the silences between those words.

Photography has a powerful capacity to capture fleeting, seemingly inconsequential moments, allowing viewers to fully grasp the complex meaning that may be contained in the simplest of details. The camera can do this better than anything, and dedicating an exhibition to such a magical property was a very good idea.

Unfortunately, although there were many extremely fine photographs on display, the idea was better than the exhibition. The quality was uneven, and some of the works seemed to be at odds with the exhibition's premise. The carefully posed and set up character of a large number of the photographs, which was often their most impressive strength, ruled out any sense of chance discovery or unexpected revelation.

This was particularly true of the three wonderful portraits by Roslyn Sharp, from a series documenting the changes in a friend's face during the last twenty years of her life. The head and shoulders portraits are all in the same formal and frontal format, and each seems to define a key phase of self-awareness. They were more like the highlights of a universal story than the spaces between words.

Ironically positioned directly opposite this sensitive study of ageing were Kate Butler's tableaux of dolls, representing eternal youth and beauty preserved in plastic. The artifice of these images is so complete that the subjects are not even real Barbie dolls but the cheaper knock-offs that the artist sensibly buys to satisfy the demands of her daughter. Butler works her material with the skill of the glamour portrait studio photographers that she parodies. The fuzzy focus looks as though it required enough gauze and Vaseline to supply a small burns ward, and the positioning of the totally brainless models creates an illusion that their painted-on faces convey subtle depths of emotion.

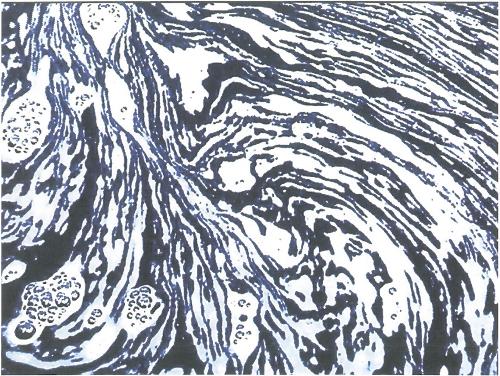

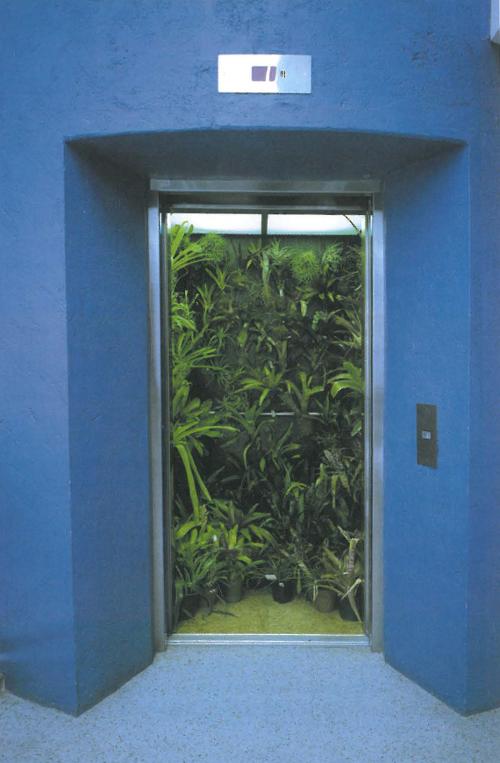

Like invaders from a different exhibition, Deb Mansfield's mysterious swamp pictures were the only examples of elaborate technical experimentation among a collection of photographs dealing with familiar human experience. Mansfield coated a wall of her living room with emulsion to develop a mural of mangroves directly onto the surface, and then used it as a backdrop for photographing other things. The disruption of pictorial space and basic normality was complete, and intriguing.

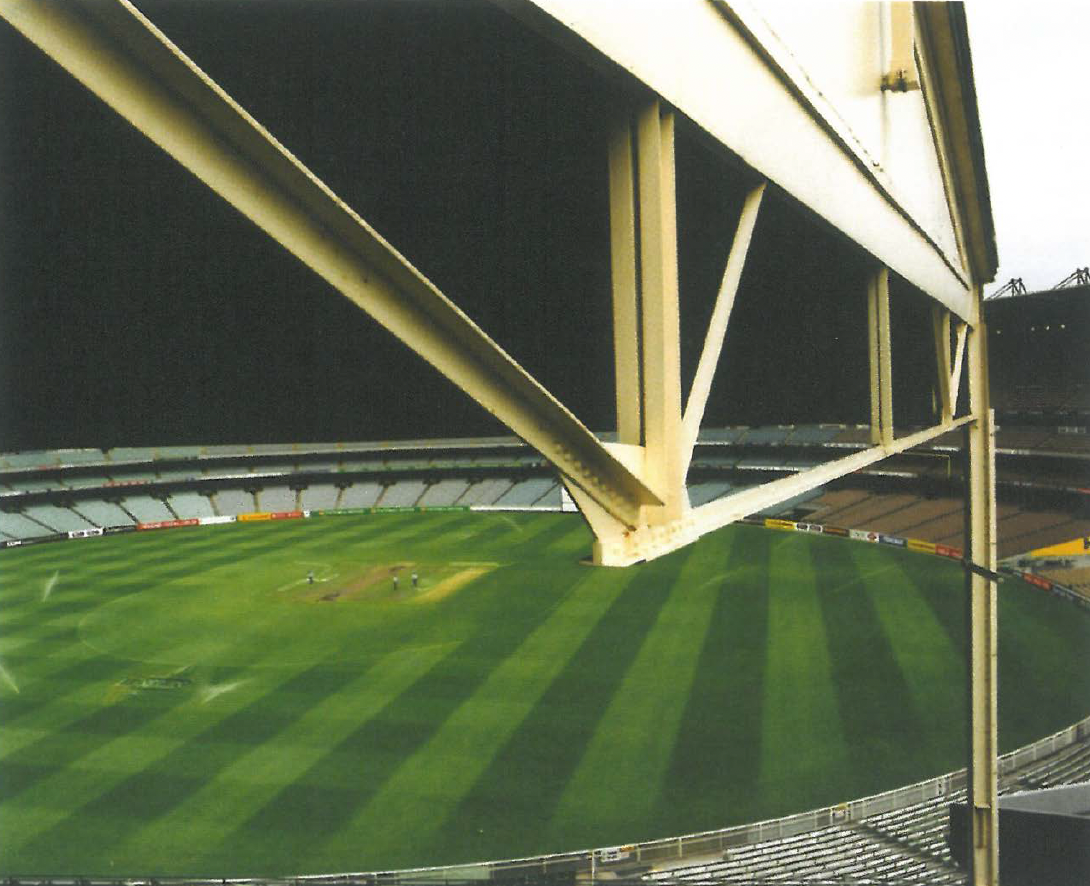

Megan Ponsford photographed a stand that was named after her grandfather at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, recording its atmosphere prior to its demolition. Most of the series consists of high-quality, straightforward, although imaginative architectural photographs. Inevitably, however, there must have been a personal dimension to this project, and occasionally the photographer's eye lingered philosophically on minor details to convey a feeling that grandeur fades and all things must pass. W Section, Ponsford Stand is a particularly striking example in which the massive forms disappear up into the gloom like a Piranesi prison, while the viewer's eye is drawn to rubbish under the benches in the foreground.

Here, and with the work of Matthew Sleeth, the exhibition fulfilled its curatorial premise most successfully. Sleeth's Rosebud series documents life at a humble beach resort in Victoria where families go for camping holidays. The knowledge that property development has sounded the death knell of the simple seaside family holiday heightens the sense in each image that Sleeth has captured something ephemeral yet significant.