When ruangrupa, Indonesia’s most experimental artist collective, was appointed artistic director of Documenta, the most significant of the contemporary art mega-exhibitions, the potential for something special, or something truly disastrous, was immediately evident. Within days of the opening on 18 June, much that was special was indeed occurring, while one disaster erupted—from an unexpected quarter, the return of a past that refuses to recede in time. Yet overall, the result looks and feels unlike every previous Documenta, including Okwui Enwezor’s ‘postcolonial constellation’ edition of 2002, when artworks more than the presence of the artists did the paradigm-shifting heavy lifting. Documenta 15 is unlike most other biennials in that it makes no attempt to survey global contemporary art. It is, however, a lot like the experimental and performance art festivals that have been staged—mostly by local artists working cooperatively, using the available resources to build local and regional exhibitionary infrastructure—in Africa (for example, Dakar) and Asia (for example, Singapore) for several decades. Documenta 15 is the most concentrated demonstration of this approach in Europe to date. How convincing is it?

The Embassy, isolated

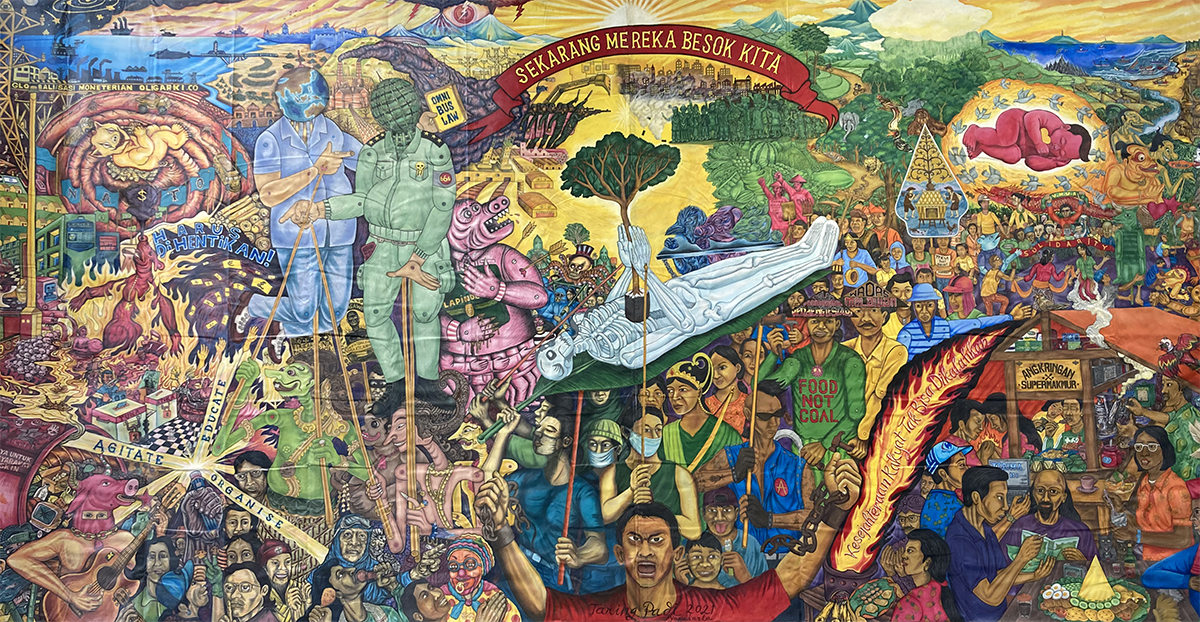

For most visitors, Documenta begins in the open space in front of the Fridericianum, with some works chosen, or the neoclassical façade modified, to indicate the main mood of the exhibition inside this edifice and at other venues throughout Kassel. A famous example occurred in 1982, when Joseph Beuys piled 7,000 menhir-like stones on the lawn, then planted the first of the same number of oak trees, a pairing repeated over the subsequent five years as part of the greening of what was then a primarily industrial city. In 2017 Marta Minujin updated her 1983 work, The Parthenon of Books—which showed 25,000 books banned by the dictators who had ruled Argentina during the previous decades—as a warning against the recent rise of populist authoritarianism on every continent. At the fifteenth Documenta, Richard Bell’s Embassy (2013–) stands alone in the central plaza. It was, briefly, complemented in its defiant anti-colonialism by a large painted banner and a crowd of puppet-like protest figures, all created by the legendry Jogjakarta-based political art group Paring Tadi. But these were quickly removed when one image within the banner precipitated a controversy that turned the opening atmosphere quite toxic, pervaded traditional and social media, and threatens to taint the impact of what promised to be the most radical Documenta to date. I will pursue the parcours as indicated by the curators, tracking the exhibition as it is presented, before returning to the controversy.

As all Australians know, Bell’s Embassy continues a history of Indigenous activism going back to resistance to British settlement, aka colonisation. It is a homage to the first Aboriginal Tent Embassy erected outside the Australian Parliament in Canberra in 1972—a structure and an activist centre that has persisted in various forms since. Dedicated to promoting Indigenous sovereignty on a worldwide basis, Bell’s Embassy has pursued its mission in several places since its first showing in Melbourne in 2013. Its basic format as an activist meeting and information space remains the same, but the connections to struggles for Indigenous rights changes according to locality. When it appeared as part of Performa 2015 in New York, for example, Darlene Johnson screened her film Redfern Story (2013), and legendry Black Panther artist Emory Douglas joined in the discussions.[1]

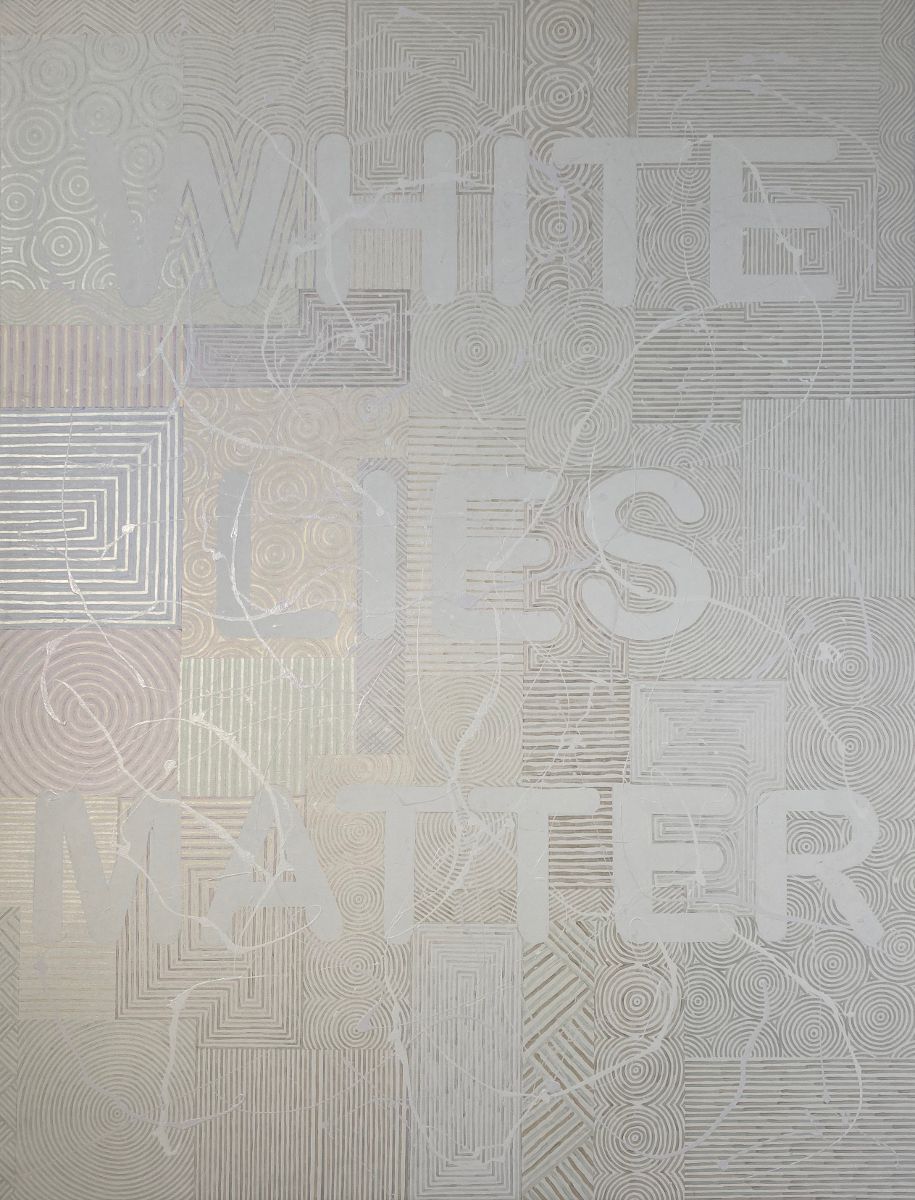

High on the façade of the Fridericianum, visible from the central plaza, a horizontal digital clock flashes numbers in the manner of the Metronome, a banal public artwork in Union Square, New York. Bell’s Metronome, in contrast, counts out the debt owed Aboriginal people for rent, fees, and associated costs since 1901. Inside the building, Bell exhibits some of his recent text and protest paintings. All Lies Matter (2022) deploys his characteristic all-over mixture of Western Desert style dotted lines and Pollock-style drips, but here fades this ground into near invisibility by the imposition of a Johnny Warungkula-style all over white veil that, in turn, acts as a screen on which the words WHITE LIES MATTER hover.

The faux universalism of the painting’s title is subverted, as it should be because it, in a further spin, evokes the right-wing, anti-Black Lives Matter slogan ‘All Lives Matter.’ Such multilayered subtlety is, however, largely absent from Bells’ suite of protest paintings shown in the upper rotunda. Each painting recalls an important moment in the struggle for Indigenous rights, in Australia and in the United States. Yet flat handling of the acrylics, and simplification of the colours, freezes the action into poster-like poses, evoking but not transforming their source photographs. To which the curatorial ethos of this Documenta replies: Even when an art museum is the context, is not the socio-political work that the image is doing more important that the artistry with which it is conveyed?

Nongkrong first, art maybe

We arrive at a challenge deliberately posited by ruangrupa, in their daily work and as curators of Documenta 15. (It is one that Bell constantly raises and mostly resolves—in the totality, if not in every instance, of his work across the decades.) Ruangrupa’s answer to this question has been projected long before one arrives in Kassel. Open-hearted sharing of whatever you bring to the collective enterprise of making the world better in whatever way you can necessarily transcends any expectations of how well, or beautifully, you might do so. This spirit pervades the entire project. Every aspect of the visitor experience has been rethought; a welcome house on the main street has replaced the ticket booths; ticket costs include public transport and are markedly reduced for many; you can, if you have the means, buy a solidarity ticket for someone who cannot afford one. If, in 2002, Thomas Hirschhorn’s work involved a fleet of dodgy cars to transport visitors to his Bataille Monument and Library in a working-class district of the city, for this iteration ruangrupa offers artist-led walks from one venue to another and countless occasions for sitting around, talking, eating, partying—for nongkrong, or ‘hanging out together.’ The venues were (in the words of the press release) not conceived as ‘a fixed, curated exhibition that remains the same throughout the 100 days,’ instead as ‘places to meet, discuss, and learn. Exhibition buildings become living rooms, and together the artists decide how to use each venue. Through this process, the rooting of artistic practice in daily life is made tangible.’

Likewise for the artists involved. Ruangrupa and the Kassel-based Artistic Team first selected fourteen art collectives (‘lumbung members’) whose conversations with each other lead to invitations to around fifty other artists and collectives (‘lumbung artists’). In turn, they were encouraged to invite other artists, groups, and activists as needed for their projects. Each was allocated an equal share (around US$ 25,000) of the production budget with no constraints on its mode of expenditure. Further, a common ‘pot’ was established to cover expenses resulting from decisions made cooperatively between the participants. This organisational form echoes that of ruangrupa in its daily operations in Jakarta.[2] It is presented here under the concept lumbung (a communal rice barn), evoking the equal sharing of available resources. The result is that more than 1,500 artivists are currently working in Kassel, constructing their exhibitions, building connections with other artists, networking like mad, planning future collaborations. They are the most visible, and vital, aspect of the exhibition.

How does this invitation play out for the visitor? Unfortunately, COVID protocols wiped out public gatherings during the week I was there. No walks, workshops, parties, anything…only the installations, the settings, and chance encounters with artists and others. I worried that this would be somewhat like going to watch a game that is suddenly cancelled, leaving us would-be spectators wandering through the halls of the stadium, bemused by the archives of past matches. In the event, not so, because every venue—indeed, almost every room and space at the several venues throughout the city—offered itself in three aspects: prominent signs and acts of welcome, including easy access, food and drink, places to sit and talk; clear documentation of past efforts and ongoing activity; and artworks made for this occasion. At most venues, these aspects arrived at a happy harmony. At others, the mix was patchy. In a few, the work exceeded even ruangrupa’s open-ended curatorial brief, with, as we shall see, interesting results.

Pursuing the parcours

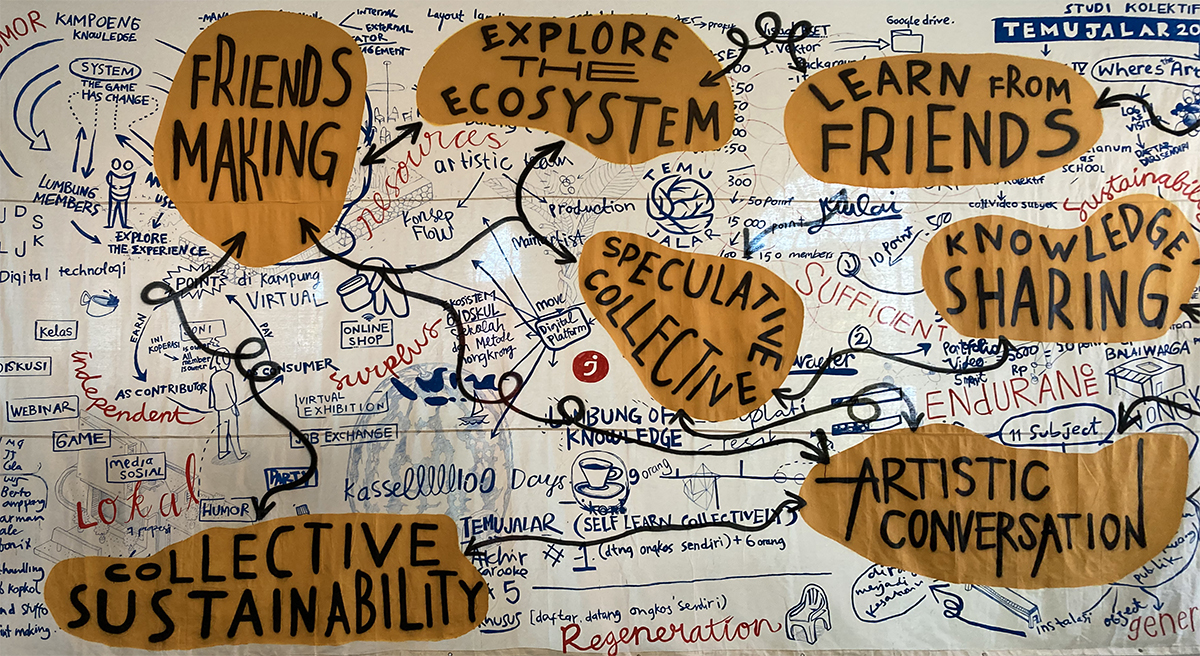

After experiencing the directly political demands raised within Embassy, the exhibition’s more general ethos is playfully announced at the traditional introductory spaces. Dan Perjovschi’s Horizontal newspaper (2010–) is chalked across the forecourt of the main railway station, and his lively graffiti scrawls all over the Fridericianum’s neoclassical columns. Wry, pointed visual barbs at the absurdity of world politics, prevalent attitudes, and prejudices about art are his forte. On entering the Fridericianum, we find the central rotunda arranged as a meeting space, sadly unusable due to COVID restrictions. The main ground floor galleries to the left were converted to a child-care centre (RURU KIDS), while those to the right introduced ruangrupa itself, mainly through wall diagrams of its organizational formlessness, videos explaining these practices, and charts of Gudskul’s friendship based nongkrong Curricula.

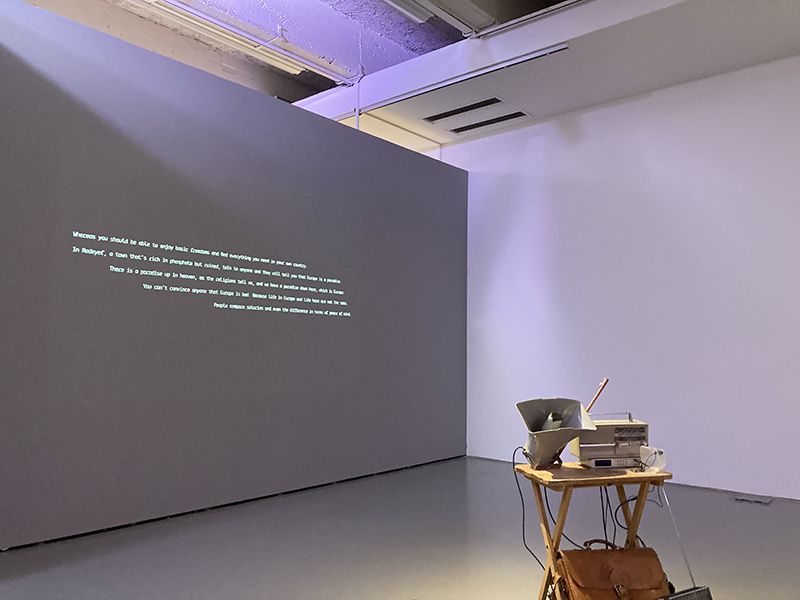

Upstairs, Off-Biennale Budapest made its spaces into a prefiguration of what might be shown at a possible/probably impossible Museum of Modern Art for Roma peoples. ‘RomaMOMA’ is proposed here as a playground space around which hung artworks ranging from folk art watercolours through elaborate tapestries by Małgorzata Mirga-Tas to Tamás Péli’s Birth (1983), a highly symbolic, mural-scale evocation of Roma history during the twentieth century.[3] In much of the rest of the Fridericianum, archival exhibitions evoked details of recent struggles for liberation from authoritarian and colonial rule. Among these, the Asia Art Archive, Archives de luttes des femmes en Algérie, The Black Archives, Komîna Fîlm a Rojava, and Siwa Platforme—L’Economat at Redeyef, were the most engrossing. The last shifted the usual compilation of artefacts, documents, text explanations and videoed talking heads toward an installation in which some heavily used suitcases, broken radios, and a clapped-out loudspeaker were framed by wall projections of film of the desert town of Redeyef, its French-owned phosphate mine and its workers, accompanied by voice over and English running texts about the factors driving emigration.

Format and content are not always so seamlessly integrated. El Warcha, a Tunis-based design workshop, rebuilt its workspace in a wing of the Fridericianum, elaborating the usual explanatory video with an exuberant array of improvised chairs, so improbable as prototypes that they become design objects. Significant aesthetic outcomes in the form of ‘museum-quality artworks’ are a lesser concern for Project Art Works, a collective studio of neurodiverse people, based in Hastings, UK.

For its contribution, Killing Fear of the Unknown, Wajukuu Art Project clad the front sections of the Documenta-Halle in rusted corrugated iron, evoking their base in the slums of Nairobi, creating a tunnel, a favored Maasai building shape. Such a transformation is also an apt reminder of one of the main sources of European wealth, paralleling Simone Leigh’s gesture of subsuming the Jeffersonian aesthetic of the US Pavilion at Venice beneath an African thatched hut, evoking the display of colonial possessions, including native peoples, at Worlds Fairs well into the twentieth century. ‘Wajukuu’ means ‘grandfather’ in Swahili. The Art Project is a kids and youth welfare organisation that uses artmaking as its central motivator and self-funder, enabling a sports club, a library, and scholarships. Inside the dark interior of the Documenta-Halle, some indifferent paintings, and three elegant, minimalist installations. Among them, Ngugi Waweru’s curvilinear screen composed of tightly compacted, much used knives seemed a succinct and subtle instantiation of the project’s title.

In contrast, the Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt (INSTAR), founded by the implacable Tania Bruguera, tackled head on the challenge of the white cube central spaces of Documenta-Halle by presenting four instances of its multi-faceted efforts to pursue independent creativity in Cuba, a society in which Fidel’s rubric ‘Inside the Revolution, everything’ continues to prevail. The implication for Cubans with a different conception of revolution was vividly visualised in one space: a wall filled with an expanding cloud of names of intellectuals and artists persecuted by the state, below which hoods with their imprinted faces were placed atop a forest of wooden stakes. In another space, we were invited to walk (shoeless) across a floor featuring a large map of the island and to experience an installation about ‘operational factography’ inspired by the Russian constructivist Sergei Tretyakov, presented as a model of creative collectivism quite counter to the imagery of constraint and censorship all around it. In another section, a display entitled “Curators Go Home!” was not a rejection of curating as such but a recreation of the first occasion, in 1994, when the artist Ezequiel Suárez and curator Sandra Ceballos refused governmental censorship of their show in a Havana gallery, instead taking the works back to the artist’s house, opening the exhibition there and calling it Espacio Aglutinador. Schematic architectural forms evoked this space. Some archival photographs are stapled roughly to one wall. For another exhibition under the title, Caballos invited artists to show any works they wished. Her manifesto is displayed, along with a painting from the original show and some paintings by Ceballos herself. The fourth INSTAR exhibition is a series of displays and conversations taking place in Havana, changing every ten days, that match those occurring during Kassel’s 100 days.

Few other artists or collectives repurposed the white cube so successfully. Agus Nur Amal PMTOH’s installation Tritangtu should have been a natural at Grimmwelt, a fascinating labyrinth that encourages exploration of the brilliantly allusive, language-intensive conceptual worlds of the brothers Grimm. A consummate, convincing storyteller, a veteran broadcaster, and a lively contributor to Gudskul, Amal’s assemblages of found materials, mostly plastics, intended as jokey conjunctions, looked awkward in the conventional temporary exhibition space assigned to him. Here as elsewhere throughout the main venues, the glare of the white cube cruelly exposed the shortcomings of the ‘everyone is an artist’ equanimity so earnestly projected as the message of this Documenta.

Repurposing for good purpose

As elsewhere throughout the world, repurposed spaces afforded more congenial settings for several contributions. Redundant industrial sites such as the Hübner areal proved ideal for the multi-media aesthetic developed since 2009 by the Foundation Festival sur le Niger, as well as quiet, out of the way venues for Kiri Delena to show films about the brutal repression of Communist agitation in the Philippines. It also worked for Subversive Film, a collective active between Ramallah and Brussels, showing restored footage of radical films combined into a work by British, German, Italian, Palestinian, Egyptian, and Japanese filmmakers. This program echoed one of the most effective spaces in the 2002 Documenta, where a retrospective of Palestinian film was shown in Documenta-Halle, affording what was then a rarely seen insight into Palestinian perspectives on the region. The Hübner areal spaces also documented the ongoing work of several arts welfare organizations: Project Art Works as mentioned before, but also Copenhagen-based Trampoline House which works to mitigate the increasingly rejective nature of Danish attitudes towards asylum seekers. Surrounded by infographics mapping this policy shift, one could watch affecting video testimonials to the life-saving work of the organisers while marvelling at the sophistication of the protest parade and cakewalk costumes conjured from discarded materials by fashion designer Dady de Maximo Mwicira-Mitali and Trampoline House resident Joachim Hamou.

Also in the Bettenhausen area, a different kind of repurposing is evident in the transformation of St. Kunigundis Church by Atis Rezistans, an artist collective based in the Grand Rue neighbourhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. In this deconsecrated space, the Christian imagery of the altar area is literally taped over while throughout the nave found object assemblages by sculptors such as Jean Claude Santillus (aka Kaliko) substitute for the Holy Family, while other artists introduce a range of cyborg hybrids. Members of the closely associated Ghetto Biennale contribute sculptures, videos, and an architectural evocation of the artists’ neighbourhood hangs from the ceiling. The fruit of collaborations dating back to the late 1990s, the internal coherence of their wild aesthetic powerfully integrates the curatorial mantra established at the outset.

These aspects also inform the work of one of the few European-based collectives participating in this Documenta. From its beginnings in Spain in 2009 as an exploration of aesthetic approaches to rural culture, INLAND has become a continent-wide voice urging the potentials of innovative agricultural economics. Its installation at the Museum of Natural History Ottoneum was multi-faceted, ranging from an ‘unmuseum’ space consisting of information and objects documenting its own history, through an AI-generated Lascaux cave-like space containing vitrines of microbiota that serve as the basis of INLAND’s proposed currency, the cheesecoin, to Hito Steyerl’s film Animal Spirits. Ironic, wacky, but also full of references to pertinent worldwide problems and the vicissitudes of trying to solve them equitably and sustainably.

Manifold exception

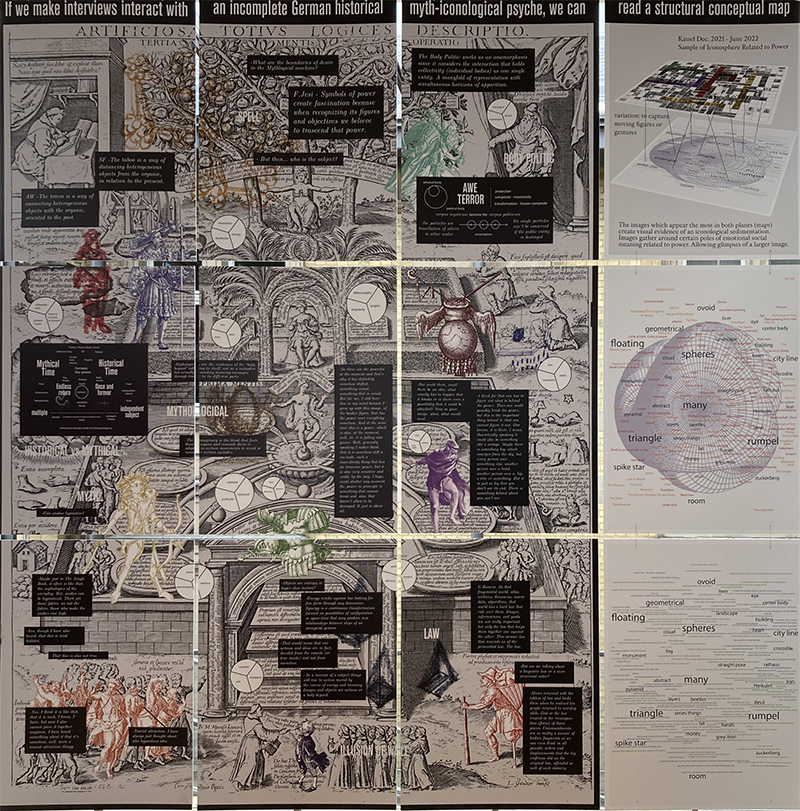

Throughout this Documenta, locality is taken to be the basis of real value, the source of true knowledge, and the place where problems, mostly caused elsewhere, cry out to be solved. Barcelona-based Mexican artist Erick Beltrán began his project by working with a team of researchers from the University of Kassel to ask residents to describe the images that arise when they think about power. Manifold is shown in the temporary exhibition spaces of the Museum for Sepulchral Culture, Kassel. These open-sided spaces hover above the lower levels of the Museum, which house gravestones, coffins, funeral carriages, and similar paraphernalia from Europe and elsewhere. The combination evokes one of the most stunning gestures in recent curating: The Brain, located in the central atrium of the Fridericianum, where Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev introduced her Documenta 13. It also resonates with the engrossing exhibition Human Brains: It Begins With An Idea, curated by Udo Kittelmann and artist Taryn Simon for the Prada Foundation at the Ca’ Corner della Regina during the current Venice Biennale.

Beltrán brought to this inquiry his own conceptualisation of how particulars appear within generalities and vice-versa: the manifold. This brilliant figure enables him to array details of what the researchers found within larger currents of world picturing. These are presented using outstanding production values (no scrap materials or DIY here) as iconographic collages almost Baroque in their dimensions, as image arrays across mural sized surfaces (some genuinely witty—'Rumpelputin,’ anyone?), and as maps that vividly diagram usually obscure mental relationships. In these forms, his ability to clearly show the operations of world picturing as humans undertake it in our moments of clarity is matched by few others among artists, and few among those philosophers who have this as their main job. Beltrán is, however, less successful in communicating the simplicity of these complexities when he turns to big banner statements, records of random conversations, and rather clunky sculptures. It is true that Kassel specifics disappear—and along with them, the locality ethos of this Documenta—under the force of his drive to show the beauties of the intellectual machinery of world picturing as such. But this is, to my mind, not a problem. Every vision needs an outlier to come into focus.

The “Antisementa” controversy

In the press release announcing their appointment as artistic directors of Documenta 15, ruangrupa set out its fundamental political position: ‘If documenta was launched in 1955 to heal war wounds, why shouldn’t we focus documenta 15 on today’s injuries, especially ones rooted in colonialism, capitalism, or patriarchal structures, and contrast them with partnership-based models that enable people to have a different view of the world.’ This is third current practice, Asian contemporary art space style.[4] It is inspired by second current postcolonial critique tied to direct political contestation, long-term life and death struggles for rights, pursued through cultural means, above all the example of the Jogjakarta-based group Taring Padi. Taring Padi’s politics of direct engagement are manifest in their display of twenty years of work at the Hellenbad Ost.[5] This is the most powerful single space at Documenta 15, although we have seen that some at Hübner areal, and Beltrán’s installation, come close.

Ruangrupa regularly avows that it aims to achieve its goals through non-confrontational, non-ideological means, above all through the forms of conviviality themselves. Ironically, it was an affiliative gesture, and an appropriate homage to their local predecessors Taring Padi, that precipitated the controversy is seriously clouding such efforts. As mentioned, Taring Padi was invited to occupy the other section of the Friedrichsplatz, partnering Richard Bell’s Embassy, a pairing of powerful anti-colonialist projects. The collective chose to fill the lawn space with a crowd of their puppet protest figures painted onto cardboard, and to feature a large canvas The People’s Justice, made first for the Adelaide Festival in 2002. It depicts the local and international forces that converged to destroy efforts to socialise Indonesia’s economy in the 1960s, culminating in the massacre of at least one million political dissidents, including most members of the Communist Party. It also shows the resistance to this oppression and elements of the emerging Reformasi movement. In Diego Rivera style, these forces are personified by portraits of individuals and by stereotypical figures long used in radical representations: satanic capitalists, pig-headed police, robotic soldiers, exploited workers, in contrast to hard-working peasants, thriving village economies, and banner-waving protestors on the march. At the top, a committee of revolutionaries meets to dispense a fiery justice to the oppressors.

Having undergone repairs, the canvas was erected on scaffolding just in time for the opening events. Then someone noticed that one of the grotesque figures doing the oppressing was depicted with demonic teeth, Orthodox Jewish hair ringlets, and bowler hat marked with the insignia of the SS. And that one of the pig-faced soldiers has “Mossad” on his helmet. If the latter has a factual basis in Israeli intelligence agency Mossad’s active support of Indonesia’s New Order regime, the other image—however small it might be, however much one among hundreds in the painting, and however confused its semiotics (‘SS’ on an Orthodox Jewish prayer hat?)—cannot escape the charge of being anti-Semitic. Accusations came thick and fast, from the President of the Republic through populist politicians to street interviews with aroused citizens. The Documenta management, ruangrupa, and Taring Padi quickly issued apologies. The painting was first partially covered, fully covered, and then removed. It emerged that the management and the curators had given an undertaking to the Central Council of Jews in Germany that no anti-Semitic material would be shown (such consultation is apparently a common practice in Germany, in light of its egregious record of cultural and institutionalised anti-Semitism). They admitted to their failure to do so in this case. Local support for Documenta, often fragile, seemed further endangered.[6]

Ruangrupa and Taring Padi avowed that they had no anti-Semitic intent in either the original painting of the mural or its showing at Documenta 15. Noting that no such objections had been levelled at the painting before, they attributed the response to the ‘special situation’ created by the Holocaust having become state policy in Germany under the Nazis.[7] This is naïve. It implies that such imagery would not be read as anti-Semitic anywhere else in the world; that outside Germany it is, simply, part of the normal contest of images. This would be so only if anti-Semitism were itself taken as normal, which regrettably it often is—including, it seems, in Indonesia at the moment of conceiving this mural. Or, at the very least, in Jogjakarta at the moment of doing this part of the painting.[8]

There are some subtle questions about responsibility within collective practice in play here. Taring Padi was and remains a group with mobile membership. Internal constraints are few, artworks are made quickly as responses to particular situations. Its products, especially the large-scale murals, are produced by many hands, signed by many names, but understood to be authored by the collective as a whole. Yet ‘All for one; one for all’ works in every direction. Powerful artistic statements, effective imagery, as much as oversights, mistakes, or, in this case, anti-Semitism have to be owned by all concerned. It is the case that Taring Padi and ruangrupa are inclusive—to a fault, it seems—in their practice and ethos. Does this secure their claim that this anti-Semitic gesture was unintentional, a kind of regrettable but forgivable accident, for which they are sorry and will not do again? No, racial stereotyping cannot be unintentional, even when—as may have been the case here—it is thoughtless. If done instinctively, that’s worse. Visual artists can’t claim to create images and not do so at the same time. In fact, a similar figure appears in another banner painting done around the same time, for the Scarecrow Festival in Delanggu Village, Klaten, Central Java in 1999. On exhibition at Hallenbad Ost, it shows a triumphant crowd of revolutionary peasants, intellectuals, workers and clerics, led by Taring Padi, marching proudly towards the viewer. They parade of cage of undesirables: a general, a corrupt politician, a policeman, a US soldier, and a capitalist with top hat, prominent profile, and braided hair curls.

As Meron Mendel, Director of the Anne Frank Educational Centre at Frankfurt am Main stated during a debate on 29 June, anti-Semitism is what it is whenever and wherever it occurs. This debate, held at Kassel during my visit, brought out other aspects of the controversy, many scarcely noticed in the (absolutely appropriate) rush to protect artistic expression from institutional constraint, special interest censorship, and populist political manipulation.[9] Which piled on, gleefully. Opponents of artivism celebrated this moral failure on the part of those agitating for a higher ethics in public life, delighting in a proof that collectives cannot police themselves. Conflations defending the state of Israel from any criticism arose as quickly as those condemning the charges of anti-Semitism as themselves a Zionist plot.

None of this is relevant to the image in question. The basic point is that anti-Semitic imagery directly, viscerally hurts all Jewish people. More broadly, whatever the qualifiers, racist imagery is what it is whenever and wherever it appears. It reduces every individual it identifies to a less than human state. It begins the process of nominating them for extinction. It cannot be gainsaid, however righteous the larger cause within which it appears.

Even so, I do not support removing The People’s Justice from the exhibition, nor the puppet figures from the Friedrichsplatz, leaving Taring Padi present there only in a small viewing module in a distant corner. In hindsight, it is easy to observe that a sharper eye for detail and a greater sensitivity to changed conditions twenty years later might have counselled showing Taring Padi’s most recent banner painting, Sekarang Mereka, Besok Kita (Today they’ve come for them, tomorrow they come for us), made last year with this Documenta in mind, along with a selection of the puppets, in the main plaza.

This painting is as politically uncompromising as the earlier work, is a powerful visual statement, and is up to date in its concerns. It does not trade in stereotypes. The People’s Justice would find an appropriate place at Hallenbad Ost, as one work among the 200 others shown there in an art historical retrospective that traces the evolution of the collective’s work, its successes and failures, since the 1990s. This approach parallels the decision of the German Federal Court of Justice, made on 14 June, four days before Documenta opened, to uphold two lower court rulings that a medieval Judensau sculpture on the exterior wall of a church in Wittenberg where Martin Luther preached anti-Jewish sermons should stay, on the grounds that it was of historical value and that efforts had been made to contextualise it.[10]

A final thought on what this exhibition tells us about the strengths and limitations of collective practice, especially when we compare that of ruangrupa to Taring Padi. The most obvious difference is generational. In its early years, Taring Padi was engaging in a political struggle that, recent history demonstrated, could turn deadly at any moment. Members remain aware that they will always be outsiders relative to institutional power. Although founded only 10 years later, ruangrupa has operated within a framework in which such a threat is less imminent. Its members operate less confrontationally, both outside and within institutional frameworks, especially cultural ones—in Indonesia especially, and now the world. The other collectives exhibiting at Documenta 15 share qualities of both, always tailoring their enterprises to local possibilities and dangers. Their enterprise keeps on proving that the spirit of de-institutionalisation that has driven experimental art since the 1960s is, indeed, renewable.[11]

Each collective has arrived at a distinctive balancing of the three aspects mentioned earlier: open collective practice; self-documentation and public education; and the continuous production of artworks. At Documenta 15, ruangrupa itself, which includes some practicing artists among its core members, did not show any artworks under its name or theirs as individuals. Perhaps the totality of Documenta 15—including all spin-offs, not excluding the controversy—is that work. This is an intense instance of curating as an ‘open strike’ practice, which I strongly advocate.[12] Its success remains, by definition, an open question.

It is, at the same time, becoming an open wound. On 6 July, Ade Darmawan, long-time ruangrupa member, appeared before the German parliament to apologise again and to assure them that Israeli and Jewish artists were among those presenting at Documenta but, at their request, did not name them. He should not have had to do so, as Documenta, unlike Venice, is not about national representation, but such distinctions are blurring in this heated climate. Concern about the ability of the Documenta organisation to adequately foster dialogue about the issues is growing. Meron Mendel resigned from his consultancy role, and artist Hito Steyerl withdrew her participation, saying ‘I have no faith in the organization’s ability to mediate and translate complexity.’[13] This goes to the heart of what Documenta, curating, collectivity—indeed, art as such—should be about.

Footnotes

- ^ Part of a program curated by Bell and the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, in which I participated as advisor to Performa and presenter.

- ^ The best profiles of ruangrupa are by scholars with Australian connections, both students of John Clark. Check out Thomas J. Berghuis, “ruangrupa: What Could be ‘Art to Come’,” Third Text, vol. 25, no. 4 (2011): 395-407; and David Teh, “Who Cares A Lot? Ruangrupa as Curatorship,” Afterall, vol. 30, no. 1 (Summer 2012): 108-117.

- ^ See Anna Lujza Szász, “Some Thoughts on the Roma Museum of Contemporary Art” at https://eriac.org/romamoma-anna-szasz/.

- ^ On the main currents in contemporary art, see Terry Smith, Contemporary Art: World Currents (London: Laurence King, and Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2011), and Art to come: Histories of Contemporary Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

- ^ See Taring Padi, “About Taring Padi,” a history that includes their founding statement and list of “Five Evils,” beginning with “Art for art’s sake,” at https://www.taringpadi.com/?lang=en.

- ^ For a journalist’s balanced read of the exhibition and the impact of the controversy, see Siddhartha Mitter, “Documenta Was a Whole Vibe, Then a Scandal Killed the Buzz,” New York Times, June 24, 2022, at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/arts/design/documenta-review.html. It is a historical irony that The People’s Justice attracted little negative commentary during the 2002 Adelaide Festival, perhaps because the Festival itself was busily generating its own controversies, not least by trialling a series of television advertisements showing prominent artists with Adolf Hitler’s face substituted for their own above a caption suggesting that if Hitler had been accepted into the Vienna Art School the Holocaust may well have been averted. Historical blinkers are not confined to Indonesian artist collectives. They are, however, less inclined to such flip stupidity.

- ^ “Ruangrupa and the Artistic Team on Dismantling The People’s Justice,” June 23, 2022, at https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/news/ruangrupa-on-dismantling-peoples-justice-by-taring-padi/. “Statement by Taring Padi on Dismantling People’s Justice,” June 24, 2022, at https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/news/ruangrupa-on-dismantling-peoples-justice-by-taring-padi/. On their website at https://www.taringpadi.com/updates/?lang=en.

- ^ The best discussion to date, informed by interviews with Taring Padi members, is by Melbourne-based scholars Wulan Dirgantoro and Elly Kent, “We need to talk! Art, Offence and Politics at Documenta 15,” new mandala, June 29, 2022, at https://www.newmandala.org/we-need-to-talk-art-offence-and-politics-in-documenta-15/.

- ^ See Anti-Semitism in the Arts, Symposium, June 29, 2022, Documenta YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B6plSiv-vTI. There was, however, a total failure to discuss the works that precipitated the crisis—indeed, to discuss any artworks at all, apart from an allusion by previous Documenta director Adam Szymczyk to an early work by Anslem Kiefer (Occupations and Heroic Symbols, 1969).

- ^ See Carol Schaeffer, “Hatred in Plain Sight,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2020, at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/germany-nazism-medieval-anti-semitism-plain-sight-180975780/.

- ^ On this question, see Terry Smith, “Is De-Institutionalization Renewable?”, in Defne Ayes and Brik van der Pol eds., Were It As If: Beyond An Institution That Is (Rotterdam: Witte de With Contemporary Art Center, 2017).

- ^ See Terry Smith, Curating the Complex & The Open Strike (Berlin: Sternberg Press for School of Visual Arts, New York, 2021).

- ^ Cited Taylor Dafoe, “Artist Hito Steyerl Has Pulled Her Work from Documenta,” Artnet, July 8, 2022, at https://news.artnet.com/art-world/hito-steyerl-pulls-out-documenta-2144265. For an earlier roundtable following the trashing by rightwing activists of a installation by the Palestinian collective The Question of Funding at AAA, a Kassel contemporary art space, Steyerl had prepared a presentation outlining instances of anti-Semitism at previous Documentas. The roundtable was cancelled. A further one is promised later in July.