You start on the artificial lawn outside a suburban house. You know it’s Australian, because the tyre swan is black and beckoning with a jovial red beak. The neighbour’s dogs are casually making your presence known. The twin doormats read “Always was, always will be”.

Hardenvale is a series of structures within structures which reveal the ontology of the suburban home. This means it’s not simply a life-size house we’re looking at and walking through, but a pointed series of observations about what makes a building an anchor of other people’s memories. It is, ultimately, an invitation for collaboration.

Stylistically, we see touches of mid-century modernism, but it’s the informal, comfortable op-shop kind. These are coincidental relics of another era in which we find ourselves, not a dedicated aesthetic drawn from glamorous magazines of Australian design or international style. When walking through the rooms of Hardenvale, we are regularly reminded of the metaphors of permeability and opacity.

We glean hints of the next room through shadowy transparent white sheets, traced like drawings. Sometimes we can see through walls clearly, only to be locked out, unable to trespass within. The walls are draped textiles, pinned paper, and aged linoleum and particleboard. In a room we cannot see, someone else might be watching TV or playing a radio, one of several soundscapes developed by Mick Dick for this exhibition.

Collectively, Hardenvale is not an easy exhibition. Indeed, the defining atmosphere of Hardenvale is a sense of unease. The narrative could be told in so many words, spoken by the three artists straight to camera or written on lengthy wall texts, like a novel dismembered and re-arranged page by page. But that would be too easy. When seen room by room, it helps to know that this is an ergodic narrative: a story in which the reader must think carefully to create coherence.

Like the novel House of Leaves (2001) by Mark Z. Danielewski or the “Griffin and Sabine” correspondence by Nick Bantock, Hardenvale provides a puzzle that cannot be completely solved, but it can readily be interpreted. It is never quite concluded, and changes shape on every manifestation, with different “events” for every visitor. Though presented as an open home, one does not simply take a tour of the house – this house visits you.

Hardenvale is the result of an ongoing collaboration, so it does not feel like a house museum dedicated to one person’s life. Objects aren’t fetishized as sacred, original relics. Instead, the shared memories are episodic, starting with one storyteller and finished by the visitor. Our own story is woven into this narrative by asking us, “what does a suburban home mean to you?”. For Kellie O’Dempsey, Catherine O’Donnell and Todd Fuller, it means different things. By splitting this story in three directions at the outset, our pathway is made much more nuanced and complex.

It may help to connect Hardenvale to the broader conception of the suburban gothic. Since it first became popular in the early nineteenth century, there is a gothic mode for almost everything. One of the recurrent features of the gothic mode is that the setting itself becomes a character, not simply a background setting, but a participating force in a narrative. For example, the haunted house as an active presence that changes the dynamics of a story.

As noted by the videogame designer Kitty Horrorshow, “when a house is hungry and awake, every room becomes a mouth” (Anatomy, 2016). Hardenvale is not quite “haunted”. Indeed, much of it is shiny, precise and new, and humour can be found in each room. Instead, the setting of Hardenvale is a stage, inviting your own memory as a character, prompted by hints from each of the three artists.

These hints are dropped through the artists’ own experiences of home. These play out as a series of acts, each room a stage, foreshadowing the next. Todd Fuller recalls his neighbours’ dogs, childhood pets and the “Guinea Pig Castle” of the Wagga Wagga Botanic Gardens (in which, according to local legend, a lucky person might witness the emergence of the Queen, distinguished by a crown). Fuller’s freely animated kitchen recalls his mother’s compulsion to repeatedly wash the windows, and records the tidal cycles of the kitchen sink. His animated drawings are quickly formed and erased, bombastic and dynamic, and provide one of three distinct voices throughout Hardenvale.

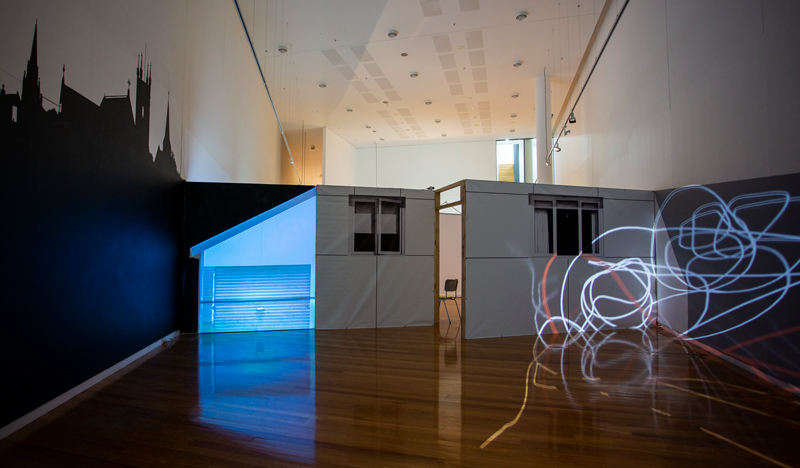

By contrast, Catherine O’Donnell observes and delineates with formality and verism. Her drawings carry the certainty of an architect’s plans, engineered and executed as simulacra. They stand in as light switches, windows, shutters and blinds. Her work extends to delicate models of the facades of neighbouring houses, each specific to the city in which Hardenvale manifests.

These drawings contribute a calm confidence that catches visitors by surprise, as what appears to be real is not. In a similar way, the kitchen wall is bifurcated by table, a chair to either side. It appears open and inviting, but it is distant and detached from our reality. The open ceiling borrows the architecture of the high and wedge-shaped gallery itself, lofty yet claustrophobic as the house gradually narrows.

Kellie O’Dempsey’s work is far more gestural, spiralling with motion and digital works, including distorted soundscapes and film footage. Her drawings are most evident as we enter the final room of Hardenvale, the backyard, in which we are met by projected pirouettes of digital lines, curved and spiralling around us. Her childhood was spent moving between pubs across regional Australia, reflected in a mountain of cardboard packing boxes rises like a precarious ziggurat, hosting scattered lamps that grow like ferns from an old rockslide.

Upon the ceiling, a hills hoist revolves skyward, and a familiar skyline of telephone wires and churches recedes. A landline phone rings unanswered, as we hear draining water and flickering flies, like the snow of no TV reception. Concealed in a cardboard box, pink sausages are slowly turned on a tiny, secret BBQ. (Like the guinea pigs, there are curious reassurances in this strange house for children to discover).

Somewhere, I am told, there is a reference to Wagga’s famous five o’clock wave, but we could be waiting a long time to see it.

Of all the collaborative moments within Hardenvale, one stands out as an iconic and memorable sequence. A comfortable old armchair, draped with a colourful crocheted blanket, is parked under a lamp. A pile of newspapers lies on the floor nearby. The cover image is a race horse, illuminated by a secret spotlight. In a surprise that is both eerie and charming, the horse’s legs begin to gallop, and it slowly gambles across the floor, leaving the newspaper to slide under the wall nearby.

Breaking the fourth wall even further, our eyes find the framed newspaper clipping of champion greyhounds. These allude to O’Dempsey’s father’s gambling, in which the portraits of winners were cherished while human family was overlooked in a phenomenal devotion to his dogs. This uncanny animation and installation is an inversion of the “straight to the pool room” ethos of The Castle (1997), in which a family’s diverse achievements were proudly memorialised as trophies.

On leaving Hardenvale, visiting children have built a temporary neighbourhood of cardboard cubbyhouses with big boxes, colourfully adorned with taffeta and artificial turf. These include verandahs, dog houses, stairs and mailboxes. Their interpretation of Hardenvale reveals the layers of stories invested in any home, from those initially experienced by children or first-time visitors, to elaborate and vivid blends of nostalgia and history recalled by those with longer memories.