In this exhibition featuring ten local artists and collectives ACE Open has presented an expansive model of exhibition-making. If the future is to be worth anything is less of a survey and more of an attempt to encapsulate the concerns of our time through supporting artists to create and present ambitious new work that broadly engages with social issues. As we find ourselves in this moment of transition, uncertain of the future ahead, there is a subdued optimism that change is now possible.

The combined curatorial interests of ACE Open’s Artistic Director, Patrice Sharkey, and Curator-in-Residence, Rayleen Forester are distinctively artist-led. This reflects the co-curators respective experience of working across the emerging scene in Melbourne and Adelaide. The show avoids hefty, overarching curatorial statements, focusing instead on giving voice to diverse perspectives. As hailed by the mantra of the Covid-19 pandemic, “We’re all in this together,” there is a sense that meaningful exchange is possible if we band together to forge new pathways.

The key is acknowledging and celebrating our differences. If the future is to be worth anything, we need more inclusive art spaces. As Sharkey and Forester observe, artistic practice has shifted after the global pandemic; “towards a more collaborative spirit that privileges the sharing of knowledge and fostering of comradeship.”[1] Quoting exhibiting artist Emmaline Zanelli, the emphasis is on the local “provoking artists to make work about their own community, their small radius of daily life, their own memories ... after being forced to stay in their own zone, artists will emerge with a new intrigue [for] their locale.”[2]

Reflecting this sense of transition, and uncertainty of the future ahead, in this exhibition there is a recurring motif of gateways and thresholds, as in the sometimes abrupt and ingenious physical division of the space between the works and working worlds, so that the visitor is continuously moving between moments of arrival and departure. The first work encountered is just such a case in point. For Toodles Galore Aida Azin currently in lockdown in Melbourne engaged the help of Adelaide-based artist Carl Giorgio to create the graffitied façade framing her painting behind a roller door.

Azin’s veiled canvas reveals a complex cultural imaginary, drawing upon her experience as a second-generation Australian-born Filipino-Iranian woman. The imagery includes Princess Jasmin, one of the few Disney representations of Middle Eastern women, as well as an advertisement exploiting Filipino women. Written in Filipino is the phrase: Ang pananatiling hiwalay ay pangangalaga sa bawat isa (Staying separate is taking care of each other). The slogan was used by the Victorian government throughout the pandemic to promote social distancing, but here seclusion takes on the more menacing form of cultural exclusion and segregation.

.jpg)

In another work, confronting the entrenched racism in Australian society, the Kaurna, Narungga and Ngarringjeri artist Carly Tarkari Dodd offers a compelling and uncompromising account of Aboriginal empowerment in the face of prejudice. The framed photographs in Sticks and Stones feature proud Aboriginal people. Each portrait is bordered by undulating lines that journey across the frames to emphasise an interconnectedness between the sitters and their continuous cultural heritage. The lines consist of dots of colour that match each model’s skin tone, illustrating the misconceptions and ignorance surrounding skin colour that Indigenous peoples continue to endure. Underscoring this point, these portraits on mirror glass feature racist comments and reductive stereotypes. As we gaze into the mirrors, the words burn onto our own faces as spectators. We are all implicated and diminished by these labels. It is here that Dodd confronts white privilege and systemic racism.

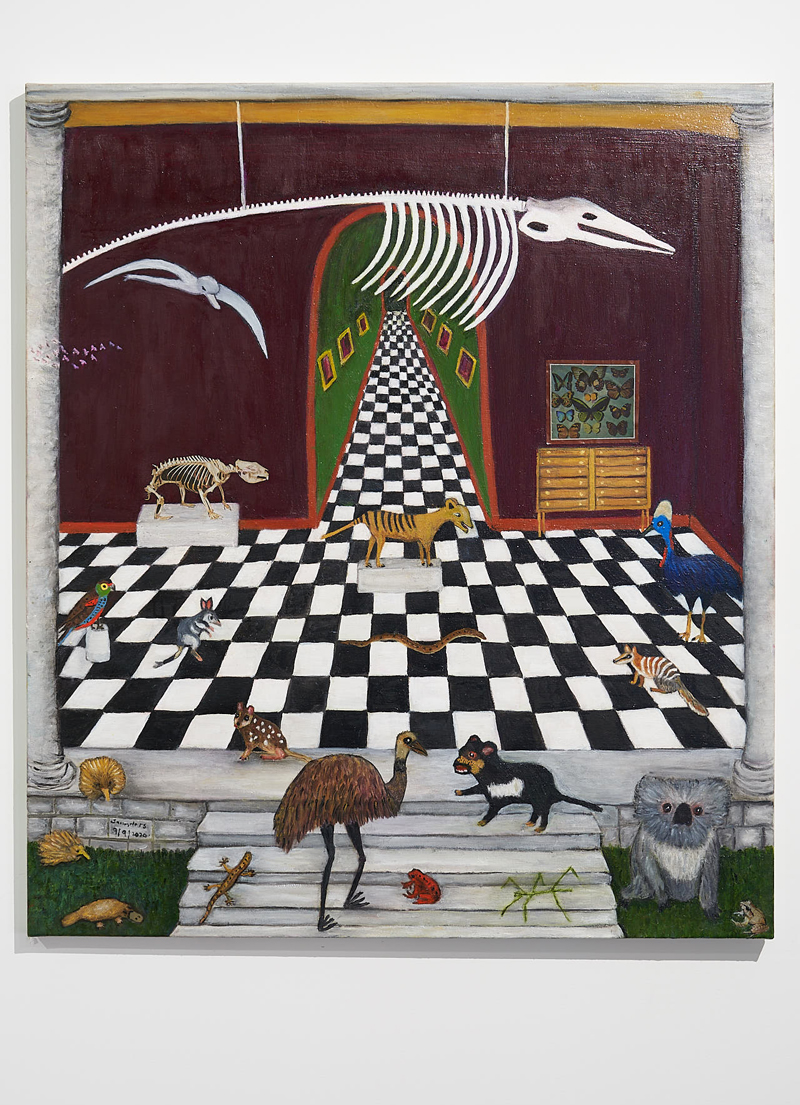

In Museum of Sorrow, the Ngarrindjeri artist and activist Sandra Saunders has painted Australian wildlife at the threshold of extinction. Here animals, such as the koala, sit at the steps of a colonial museum. The Eurocentric practices endorsed by such museums have preserved animals only in death, while the ancestral knowledge of First Nations’ cared for living creatures and their natural habitats. After many animals perished in the catastrophic bushfires at the beginning of the year, Indigenous burning practices and land management expertise has become more widely endorsed. Saunders’ narrative paintings often divulge lessons or fable-like warnings. Here she presents a cautionary tale that our unique wildlife will be relegated to history unless we listen to the cultural knowledge of First Nations peoples.

Proceeding further, upon entering Yusuf Hayat’s installation باب السلام (Baab Al-Salaam), we find our body image reflected and distorted in the mirrored surfaces and rotating planes of saturated colour in a series of Perspex doors on an axis that refers to the cardinal points of the compass. Translated as “Gates of peace,” the title refers to the gates at the Great Mosque of Makkah, traditionally the threshold through which first-time pilgrims enter.[3] Hayat’s series of doors open possibilities to a transitional space in which we can collectively gather. As our reflection merges with those of other peoples, it is as if our perspectives also converge.

Themes of unity through communal gatherings continue through the text-based canvases of Matt Huppatz, as he references 1990s dance music and queer culture. In the triptych, Lights and Music (Communicate, Release, Express), fleeting colours appear like roving lights across a dance floor while words come in and out of focus like the lyrics to an incessant beat. Huppatz’s dancefloor is a site of exhilarating transgression: the club scene, notably suspended during the pandemic, as a place to congregate and connect for LGBTQI communities. These aphorisms in pop colour are also perhaps a reminder of the recommendations of a self-help guru, now inspiring new ways to connect.

Sundari Carmody’s installation in the foyer of Ace Open is a further reminder of how architectural spaces can evoke spiritual transformations. Supporting ritual bathing as an act of purification and transition, Stepwell I is a concrete model inspired by the ritual bath at Pura Beji Taman Sari in Pejang Kawan near Carmody’s childhood home in Ubud, Bali.[4] Lightwell 1 also suggests liminal spaces where light flows between the realms of the known and unknowable. The circumference of its base is repeated in the gold leaf disc of In the Air (Meteoron). The latter denotes the Great Meteoron Monastery in Kalambaka, Greece.[5] The monastery was built high atop a rock in the hope that the physical proximity to the heavens would enable the inhabitants to the speak to the cosmos. The hanging brass loop of Orbis signals a further point of connection to cosmological events and forces outside of our control.

In another work incorporating suspension, Kate Bohunnis’ Edges of Excess prompts a symbolic reflection upon the corporeal self. Here, a strip of fleshy pink silicone is suspended between two chrome cushions while a swinging pendulum perpetually oscillates above. This exercise suggests that through pushing our physical limits, we can unlock alternative channels of consciousness.

The theme of discovery through physical experimentation continues in Emmaline Zanelli’s Dynamic Drills, where Zanelli has collaborated with her Grandmother, Mila. In the three-channel video, the pair re-enact Mila’s experiences working in factories through the creation of DIY contraptions and futile processes. As Mila recites the excited rantings of Italian Futurist, Filippo Marinetti, the words take on a new meaning, suggesting the stoic determination of the migrant labour force. Beyond the absurdity, love and care resonate between the two protagonists, and following the artist’s example inspire a better connection with the experiences and wisdom of our elders.

A room dedicated to artists from Tutti Arts is full of invention and unbridled creative expression. The program provides support for young people with learning and intellectual disabilities and was invited as a collective to showcase selected studio artists. Jackie Saunders and Tessa Crathern’s creative practice is a form of self-reflection and introspection. Crathern’s autobiographical, Patterns of Me includes photographs of her childhood-self surrounded by colourful designs evocative of stained-glass windows. Inter-connected webs span across the paintings of Ngarrindjeri and Wirangu artist Jackie Saunders. Each canvas in Family (triptych) 2020, has a different underlying colour as if to suggest the fundamental unity of kinship despite geographical distances.

Through the alchemy of their creative practices, Ellese McLindin and James Kurtze have transformed their knowledge of popular culture. McLindin’s paintings and cardboard constructions are whimsical, raw and expressive, with myriad references to movies and other icons and relics from everyday life, presented as an altarpiece in a salon hang. Kurtze’s The Kooky Time Machine is a highly crafted kinaesthetic assault on the senses with whirring mechanisms, LED lights and sporadic blasts of sound incorporated in its construction. For Kurtze, the passing of time appears to be measured by once-loved and now obsolete digital-devices.

Fantastical themes continue to emerge in the work of Kurt Bosecke and William Gregory. Guided by a joyous horror vacui, Bosecke has captured a variety of birds set in a wondrous jungle. At the same time, Gregory’s pencil drawings feature ethereal female figures with pale moon-tanned skin. Their languid poses, set against bright idyllic landscapes, reference Botticelli. Alongside Venus and her entourage, there is a reoccurring character named Urbino (also the birthplace of Renaissance artist Raphael). The unity amongst the women is undeniable as they lovingly dote on each other.

The theme of community is thematically explored by the independent online magazine fine print, edited by co-curator Raylene Forester with Joanna Kitto. They attempt to create a dialogue with the gallery space through the random scattering of bands of vinyl words, anticipating what promises to be a dynamic scheduled series of live performances, COMMUNITY – an IRL intervention, that will take place later in October.[6] This event has great potential to further dissolve the borders between arts writing, creative practice and a bigger audience. Like the exhibition itself, this is an example where the gallery can be a public place of exchange, a space to share our vulnerabilities and offer an insight into the lived experiences of others.

Footnotes

- ^ Raylene Forester and Patrice Sharkey, in foreword to If The Future is to be Worth Anything, ACE Open, p. 5.

- ^ Olivia De Zilva, “Emmaline Zanelli meditates on family work and apricots in ACE Open’s 2020 Artist Survey,” The Adelaide Review, no. 485, 23 July 2020.

- ^ Bab As-Salam, Masjid Al Haram (Madain Project), Madainproject.com, 2020.

- ^ Sundari Carmody, “stepwell” @sundaricarmody, Instagram, 17 September 2020.

- ^ Daniel Stone, “This Clifftop Monastery Is Surprisingly Accessible,” National Geographic Magazine, 4 February 2020.

- ^ The fine print LIVE IRL intervention will be held on Saturday 31 October 2020, 2–3 pm at ACE Open.