The annual Desert Mob exhibition is essentially curated by its participating Aboriginal art centres, yielding a richly varied exhibition. Yet often a theme seems to emerge, something in the air, common to art centres of distinct language groups working at significant geographic distance from one another. In 2019, Desert Mob’s 29th year, that “something” constellated around men: fathers honoured by their artist offspring painting for Iltja Ntjarra in Alice Springs; men bursting onto the scene at Nyinkka Nyunyu in Tennant Creek; men, old and young, taking up brushes once more at Papunya, with a men’s painting space created there after a hiatus of decades.

It was perhaps a coincidence that the Papunya Tjupi and Nyinkka Nyunyu displays were installed next to one another in the largest of the Araluen galleries. Their proximity concentrated a buzz of masculine energy in that corner during the opening events. In the case of Papunya Tjupi, it was generated as much by the presence of young men with a story to tell, as by the actual hang. The showing continued to be dominated by the commanding works of women artists, some of them, like Candy Nelson Nakamarra and Charlotte Philllipus Napurrula, the daughters of illustrious early Western Desert painters, Johnny Warangula and Long Jack Phillipus respectively. They and other women have flourished as painters following the opening of the Papunya Tjupi art centre in 2012.[1]Following the Pintupi exodus from the community in 1981, the original artists’ company created there, Papunya Tula Artists, gradually withdrew to focus further west, in Kintore and Kiwirrkurra. And even as new art centres were established in surrounding communities, Papunya had remained without one.

As well as strong individual works, Nakamarra and Napurrula each had a hand in the towering women’s collective work, Kalipinypa, literally teeming with motifs of great variety – country full of life and light. The work is beautifully held together by the organisation of the composition as well as a palette confined to mainly dusty pinks and greys, kept dynamic by both dark notes and warmer highlights across the surface. Ten women were involved in the painting, four of them emerging younger artists – a granddaughter and daughters, aged 16 to late 30s.

Kalipinypa is a lightning and rain dreaming place, the subject of many of Warangula’s celebrated works. Dennis Nelson Tjakamarra, Warangula’s son, says of it: “It’s a separate country over there; it hides in the middle of the sandhill. It’s secret country, spirit country – a secret place. It’s where the snake comes up from the ground and travels west to the ocean, to bring back rain. And where the lightning comes from, travelling east …” Over forty Papunya Tjupi artists and family members had made a recent country visit there, some of them for the first time. It inspired all of the paintings in Papunya Tjupi’s Desert Mob display, including the men’s collective work, a much simpler composition than the women’s.

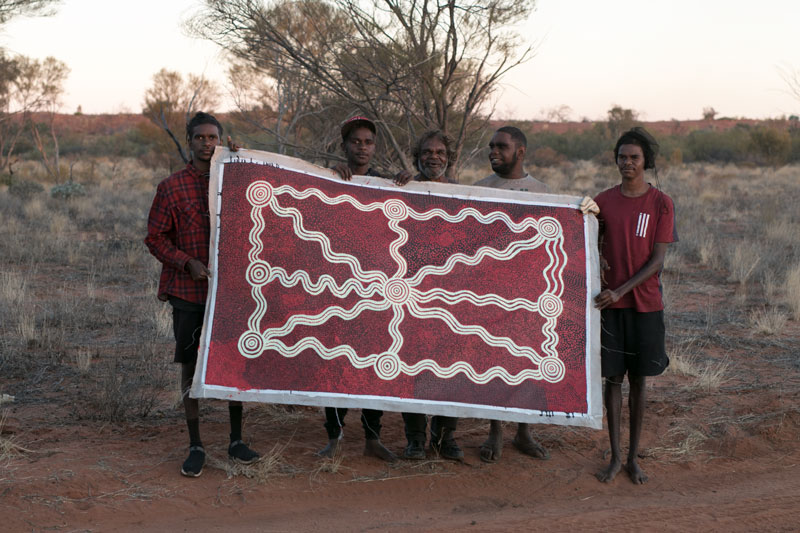

Symmetrical, its undulating parallel lines – depicting running water – converge from concentric circle motifs at the edges to a larger one in the middle. These motifs shine out in stark white over a field of red, dotted shifts and clusters of varied intensity, taking your eye across the canvas, as grasses and bushes do across the desert sands, especially after rain. Its title, Painting on Country – Kalipinypa, makes clear that it is also about its own process. A photograph of the artists, reproduced in the catalogue, begins to round out the story. Taken at Kalipinypa, it shows that four of them are young (in their late teens), standing together with Tjakamarra. “The young fellas helped me with the painting at Kalipinypa. We sat down, and I told them story. It made them really happy,” he recounts.

On opening night, one of those young fellas, Kayemyn Corby, hovered shyly in front of the Papunya Tjupi display, posing for photographers, together with one of his peers, Zachius Turner, an outgoing, confident English speaker ready to strike up conversation with anyone showing an interest in the work. Next day Turner spoke to a symposium audience of hundreds about the young men’s first painting camp and then undertook to translate for his uncle, Watson Corby, about the visit to Kalipinypa.

The camp was momentous, both for the young men, inaugurating them into the artistic practice of their grandfathers, and for the older artist Carbiene McDonald. Held in a hot week of October 2018 at an outstation not far from Papunya, itself about 240 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, it was the first time McDonald took up a brush, immediately producing a work of significant stature. He went on to win, in July this year, Australia’s richest landscape art award, the $100,000 Hadley’s Art Prize.

Meanwhile the young men were practising painting rockhole motifs – concentric circles of varying sizes – on the wreck of an old car. It was a joyful exercise in which “we didn’t leave a single space,” reported Turner. They were visited at the camp by the senior painters of the art centre. The young men cooked kangaroo tails for them, and in turn “the ladies”, as Turner respectfully called them, taught the young men to “paint our grandparents’ dreaming”.

Back in the community though men and women do not work comfortably in the same space. The art centre’s establishment was driven by the commitment of the ladies and it has effectively become a women’s space. Young men “feel a bit shamed” to work there, said Turner, so the creation of a separate men’s painting space has been vital to maintain the momentum of the last year. A first body of work by the men will be shown at the art centre’s gallery in early October.

So, almost fifty years after that original push to find a painting space at Papunya for the men of the brilliant first generation of Western Desert artists (that is, the first, in the wake of Albert Namatjira and his family, to send their paintings into the fine art world and have them received as such), the story has repeated itself. As the women, with the support of a space and staff at Papunya Tjupi, have gone on to produce wonderful new work – a vindication of the art centre model – there is excited anticipation about what will emerge for the men.

Next to them in the gallery but from the highway town of Tennant Creek, on Waramungu country 500 kilometres north of Alice Springs, another group of men have found a home for their art practice. Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre originally opened its doors in 2003, as a museum telling the Waramungu story, including first contact history, while also promoting the living culture and contemporary arts and crafts. It has been some years though since artists showing under this name have had a presence at Desert Mob.

On their return, they made their presence felt with a display like no other, clearly articulated as Wanjjal Payinti, meaning past and present. Mainstays of Nyinkka Nyunyu, Jimmy Frank and Joseph Williams, anchored the showing with, respectively, their wartilkirri (number seven boomerangs) and karlala (spears), just as at the symposium they came onto the stage with white feather headdress, singing, dancing, clapping boomerangs – emphasising the strong cultural foundation that bridges to the wild and brilliant painting by the other male artists of the group. On stage with them, in headdress too and joining in the singing and dancing, was Fabian Brown. Frank and Williams did most of the talking, about the broader mission and achievements of Nyinkka Nyunyu. Brown followed up, keeping it simple and brief: “We respect our old ways, but this is a new way of doing art.”

The new way is marked by the diversity of its explorations of meaning and experience in contemporary Tennant Creek and the surrounding region. There are untitled abstract works by the youngest of the group, Marcus Camphoo, striking for their bold geometry and colour and, up close, for their way of laying paint on the linen. There are tumultuously expressive renderings of desert storms – you can almost feel the sand between your teeth – by Simon Wilson.

Four works by Brown escape short summation. “I always knew I was an artist; I’m a creative,” he says, with a sharp awareness of vocation. He also speaks of liking to travel and has moved around Australia quite a bit. External cultural influences are immediately apparent in his work. For example, he paints an angel, a black angel of extraordinary vigour; a Samurai warrior, straight off the mean streets of a town or city somewhere (on this work Brown was assisted by a younger artist, Clifford Thompson).

Apart from urban grit, he imbues his paintings with a mythical character that is surely informed by the “old ways” in which he was schooled by his uncles. He points to this with his title for the largest work in the showing, Mystical Animals. Its human-like figures have a comic book pathos as they try to flee the scene, while giant dog- or wolf-like creatures wage a battle to the death, redolent of ancient epic stories. At the same time the work exudes an almost dystopian aura, its rough black surface – oil and enamel on hessian – conjuring the hard glitter of bitumen under streetlights, the depicted violence tipping towards frenzy.

As a highway town, Tennant Creek is open, not an Aboriginal community, unlike the context for the vast majority of art centres taking part in Desert Mob. This is true too for Alice Springs, where a number of art centres are based, but the towns have distinct histories – for one, Tennant has a strong mining history and identity, which Alice does not. The towns’ sizes, levels of resourcing and demographies are also very different. Over half of Tennant’s 3000 residents identify as Indigenous, while in Alice the Indigenous population stands at about 20 per cent of some 25,000.

These are some of the factors that feed into the capacity of the two towns to deal with their considerable social stresses. They also influence the way artists are supported, with the art centres in Alice now well-established, having studios, full-time staff and, most of them, exhibiting and retail areas. In Tennant, the situation has been recently more precarious and unstable; even Nyinkka Nyunyu went through a period of closure. But out of this – and alongside “all the bad stories” we may have heard, as Jimmy Frank said at the symposium – something remarkable has emerged.

Nurturing this since 2016 has been the non-Indigenous artist, Rupert Betheras. He brings to his engagement with the men the significant “cred” of having been a professional AFL player (for Collingwood). He was initially employed not by an arts organisation but by Anyinginyi Health, to deliver an art program as group therapy, focused on social and emotional wellbeing. It soon became so much more. As Joseph Williams has noted, “it turned out to be big – exhibitions, catalogues and all.” Betheras paints alongside the men, in a collective known as The Tennant Creek Brio.[2] His work wasn’t on show with theirs at Desert Mob, but it will be in next year’s Biennale of Sydney, together with nine Tennant artists, at both the Cockatoo Island and Artspace venues.

The biennale’s title, Nirin, means “edge” in Wiradjuri. This name and artistic director Brook Andrew’s curatorial statement could hardly be more apposite to The Brio’s work: “The urgent states of our contemporary lives,” it begins, “are laden with unresolved past anxieties and hidden layers of the supernatural.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

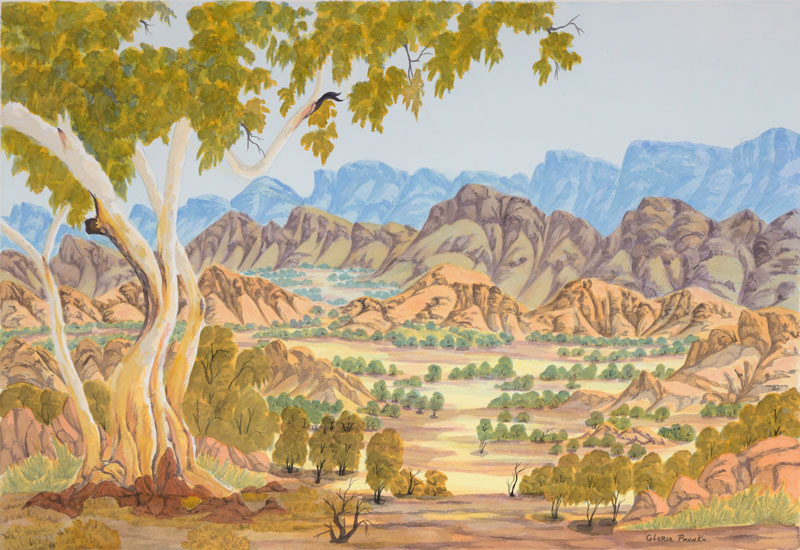

That is not so obvious in the work shown at Desert Mob by the watercolour artists painting for Iltja Ntjarra, but they too have been announced for the Biennale of Sydney. At Desert Mob their showing was in the deeply classical vein of the Namatjira School, conceived as a homage by four of their leading artists to the work of the preceding generation. In fittingly scaled-up works (roughly twice the size of the typical works of their forebears), they each “remade” a landscape rendered by their fathers, while bringing their own distinctive stylistic approaches to the task.

Hubert Pareroultja honoured a view of Tjoritja (the West MacDonnell Ranges) by his father Reuben, who together with brothers Otto and Edwin was an acclaimed artist of the original Hermannsburg School, as were Claude Pannka and Clifford Inkamala, honoured by their daughters, Gloria Pannka and Kathy Inkamala, with views of Tjoritja and Rwetyepme (Mount Sonder) respectively.

Mervyn Rubuntja’s homage was to his father Wenten Rubuntja, an important political leader in central Australia and senior lawman, who painted in both the watercolour and Western Desert styles, calling the latter “landrights painting”.[3] The subject of Rubuntja father and son’s paintings was Mt Zeil (further to the west, Urlatherrke by its Arrernte name, the starting point for the journey of the ancestral caterpillar, ayeparenye).

The tributes were as much to the process of transmission as to the specific works. All of the artists speak of starting to learn by watching their forebears paint (this experience is frequently described by desert artists). Gloria Pannka, for instance, remembers hanging around with her dad and the Namatjira brothers, trying her hand with an “empty tube” on cardboard at the age of twelve. “I thank my dad from the bottom of my heart, for what he taught me. And now, I’m carrying his tradition.” Mervyn Rubuntja at the symposium recalled a more direct instruction: “They told me, ‘You see the country and you paint the same colour.’”

But changes in the landscape have presented a problem for that observational mode. Today there is “too much buffel grass”, he said, referring to an invasive species that is spreading rapidly across central Australia. Its thick infestations have changed the colour of country, turning it vivid green after rain, drying out to a dull brown-grey. “I don’t put buffel grass,” he told the symposium audience, to murmurs of appreciation.

Despite their command of the watercolour medium and their success, all of these artists, alongside their fellows at Iltja Ntjarra, have demonstrated a willingness to experiment and diversify. Earlier this year they showed in The National at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, with a body of work about threatened plant species that combined paintings of country with lumen prints. This technique allowed them to lay plants they had collected on photosensitive paper, then expose it to sunlight and process it in a chemical bath.

The ghostly quality of the resulting images suited their sad theme, the disappearance from country of plants valued for food and as medicine (buffel grass infestation is one of the contributing factors). This limits the time they can spend “away from civilisation, to live our own lives”, as artist Clara Inkamala put it in a video shown to the symposium. Once the tea, sugar and damper runs out, there’s nothing to eat: no yalke (bush onion), no bush banana, no bush honey, and increasingly, Mervyn Rubuntja reported, no water.

Their Biennale works will be drawn from a related repertoire, what they call their social commentary paintings.[4] This vein of work has developed out of workshops starting back in 2016 with the Brisbane-based Aboriginal artist, Tony Albert. Earlier iterations incorporated iconic logos like the “golden arches” or used the packaging of mass-produced goods upon which they painted, confronting issues like diabetes, dialysis, and mining. Earlier iterations used the packaging of mass-produced goods upon which they painted, confronting issues like diabetes, dialysis, and mining. Their installation at the biennale will use nylon striped bags as their painting surface, an allusion to the painful issue of homelessness, a significant unresolved past and present anxiety for the artists and their families.

Clara Inkamala, speaking at the symposium, saw this kind of experimentation and collaboration with another artist as on a continuum with the relationship that Albert Namatjira had with his friend and mentor, Rex Battarbee. Her father, Gerhard Inkamala, only painted on board, she recalled, but now she and the others have more opportunities, are open to them and learning from them: “We want to show the world we are changing,” she said. It is this movement, between origins and the ever shifting present, renewed from year to year and in frequently surprising ways, that continues to make Desert Mob unrivalled in the central Australian cultural landscape.

Footnotes

- ^ Vivien Johnson tells the story of Papunya Tjupi in Streets of Papunya: the re-invention of Papunya painting, NewSouth, 2015, in which she also gives consideration to the connection between Albert Namatjira and his son Keith with the community and its first generation artists. For a briefer account of the advent of Papunya Tjupi, see Kieran Finnane, ‘Triumphant painting revival at Papunya’, Alice Springs News, 10 July 2017: https://www.alicespringsnews.com.au/2017/07/10/triumphant-painting-revival-at-papunya/

- ^ The nine Tennant Creek artists exhibiting as The Tennant Creek Brio with Rupert Betheras: Fabian Brown, Jimmy Frank, Joseph Williams, Marcus Camphoo, Simon Wilson, Clifford Thompson, Lindsay Nelson, Mathew Ladd, David Duggie.

- ^ See Wenten Rubuntja with Jenny Green, The Town Grew Up Dancing, IAD Press, 2002.

- ^ On Iltja Ntjarra’s early “social commentary” work, see Kieran Finnane, ‘Namatjira family: Getting listeners ‘through our art’, Alice Springs News, 6 July 2016: https://www.alicespringsnews.com.au/2016/07/06/namatjira-family-getting-people-to-listen-through-our-art/.