The OzAsia Festival is an initiative of the Adelaide Festival Centre and is largely centred on the performing arts. This year there is a substantial program of theatre, dance, music, community events and forums, with many events featuring shared input from Asian and non-Asian creative practitioners and companies. While it is a relatively small part of the wider program, this year’s visual art program includes a suite of exhibitions by Asian women artists who have strong reputations in a global context. Each of the five women artists, from five different countries in Asia, adopts distinctive artistic strategies in addressing personal and cultural issues around the role of women.

A major keynote is Absence Embodied, an installation by Japanese-born, Berlin-based artist Chiharu Shiota presented by the Art Gallery of South Australia. Her installation was seen initially in conjunction with an accompanying retrospective exhibition and an outdoor installation of three interconnected trailing red dresses suspended from the Gallery’s North Terrace façade. Embodiment of an artist’s thoughts and emotions in a visual material form is at the heart of the act of making art. There is a shifting scale between the roles of emotion and reasoned thought in this process of embodiment, with most contemporary artists leaning towards the latter end of the scale. Not so in the case of Chiharu Shiota. Few have been prepared to push embodiment of the emotional inner life to the limits in the way she has done. Few have done it with such coherence across a body of work over more than two decades.

Shiota’s Absence Embodied is a site-specific and astoundingly complex web of red wool threads, occupying one of the large older-style 1930s galleries, complete with skylights, in AGSA’s Melrose Wing of European Art. Acquired by the Gallery, to be exhibited on a semi-permanent basis, well beyond the life of the OzAsia Festival, it warrants particular attention in this review. Shiota won critical acclaim at the 2015 Venice Biennale for her poetic installation, The Key in the Hand, featuring an aerial woven forest of suspended threads of red wool in which were knotted thousands of keys, all cascading into dilapidated wooden boats. Since then she has been in demand worldwide. It was quite an achievement for AGSA to secure this first permanent installation by Shiota in an Australian public gallery, and supporting this there is a backstory.

Shiota’s initial aesthetic breakthrough in the sculptural use of thread and linear elements came during a student residency at the Australian National University in 1993–94. Since then she has developed an artistic repertoire in which she constantly returns to the poetic embodiment of her preoccupations around her body and emotions. Connectivity between her organic body and the wider organic universe is central to all the manifestations of her art practice in drawings, videos and sculpture. In addition to her woven web installations using red, black or white thread, there have been videos of her naked body rolling in mud and bathing in muddy water, long dresses draped across buildings and soiled by showers of muddy water, and the particularly disturbing video screened at AGSA of her lying naked on the floor encased in a tangled network of tubes through which coursed a blood-like fluid, as her body twitched to the soundtrack of a baby’s heartbeat.

.jpg)

Over many years of practice, Shiota has created a body of work that has its own intensely personal aesthetic language while also drawing on a lineage of European and Japanese influences – in the sculptural use of fibre (Magdalena Abakanowitz), primal pre-lingual connection with nature, transience and mortality (Saburo Muraoka, Toshikatsu Endo), and performance, bodily endurance and abjection (Marina Abramović, Ana Mendieta). In October AGSA published a substantial catalogue to accompany the exhibition that includes three essays and photo-documentation of the creation of Absence Embodied.

The first essay by co-curator Russell Kelty is particularly illuminating in respect to these diverse influences mentioned above, while an essay by Anais Lellouche considers the role of drawing in Shiota’s art. The third essay by co-curator Leigh Robb focusses on contextualising the specific aspects of Absence Embodied. This was created after a period when Shiota was treated for cancer and experienced the trauma of a sense of alienation or “absence” from her body. Robb considers Shiota’s incorporation of new sculptural elements – fragmented body parts that have been cast from her own limbs and those of her husband and child. These sculptural fragments physically anchor the web of threads while introducing nuances of mortality and bodily fragility.

Absence Embodied is a walk-through, visual and cerebral environment deeply imbued with poetic associations that embrace the personal and the universal, the microcosm and the macrocosm. Two hundred kilometres of thread have been intricately strung and knotted in a complex organic web that to close-up inspection reveals its cellular geometry of random quadrilaterals, only to transform into swirling vortices when viewed a few steps further away. It has the rare potential to momentarily immerse the receptive, focussed viewer in a different dimension to the everyday. While Shiota’s art has its own meanings specific to the artist’s emotional life and artistic development, she allows room for the imaginative interpretation by the viewer.

In the context of AGSA’s Melrose Wing of European Art – a space still imbued with the memory of those paintings from the Renaissance to Victorian era that hung there for so many years – Shiota’s approach to visualising her body as an emotional site, and finding a language to express this from a contemporary Asian female perspective, works to re-orient and disrupt the European perspective of the body seen in those paintings that have traditionally occupied the Melrose Wing. The gallery’s acquisition of such a site-specific artwork, one that ceases to exist once it is dismantled, when it will become no more than a very big ball of wool, is a daring move (but at least it does not contribute to AGSA’s critical storage issues).

At Nexus Arts, Kawita Vatanajyankur’s videos are emblematic of feats of endurance, self-harm and abasement that have been part and parcel of performance art since its early days. Originally this was one aspect of the concept of actualisation – actual pain in actual time by real people, as opposed to fictional actions by actors in the fictional time of theatre. An element of fiction did creep in occasionally, as when Mike Parr faked the amputation of his arm in one famous performance action of the 1970s. In a refreshingly original take on this lineage, Kawita Vatanajyankur adopts a quite different strategy to that of Shiota, one that grows out of a young generation’s immersion in social media.

At first glance the three videos that comprise her exhibition, Scale of Justice, may look custom-designed for a narcissistic Instagram or YouTube market with their delectable chromatic screen display and focus on the central figure of a young Asian woman performing quasi-gymnastic feats. It very quickly becomes clear that Vatanajyankur is subverting rather than reinforcing these tropes. Each portrays her enacting scenarios that would test her physical endurance to the limit in order to address issues around the domestic and industrial labour of women in Thailand.

In The Scale she lies with head and shoulders on the ground and her legs in the air, with her arms holding her back. She is supporting a crate placed on her feet, while melons drop into the crate from above, building up in weight, smashing and splattering on the ground around her, covering her in fragments of fruit and juice. In The Scale of Justice (2016) her body becomes a fulcrum as she balances two baskets of vegetables, one hanging from her neck and the other from her ankles, while more vegetables are perpetually being thrown into the baskets and her body tilts first one way and then the other as the distribution of weight changes in each basket. In the third video, The Lift, she performs the pose of an aerial gymnast, hands grasping feet from behind as she supports a heavy basket of papayas on her back. Her body is balanced on a trapeze with metal bars around her chest and pelvis as she is slowly raised and lowered in the air.

Throughout these endurance acts the artist maintains the contained stoicism and bodily poise of a yoga master. She looks young and vulnerable but shows inner steel. A balance is also effectively maintained between control and abasement. In an online catalogue essay, Adelaide writer Chelsea Farquhar has written: “The artist attempts to transform pain, fear and insecurities into power. … Pain is necessary and even crucial to this process. Through endurance, Vatanajyankur believes one can evolve as a person. She forefronts pain as a tactic of resistance, and endurance as resilience.” As Farquhar points out, the repetitive loop of the video reinforces the endless repetition of women’s labour.

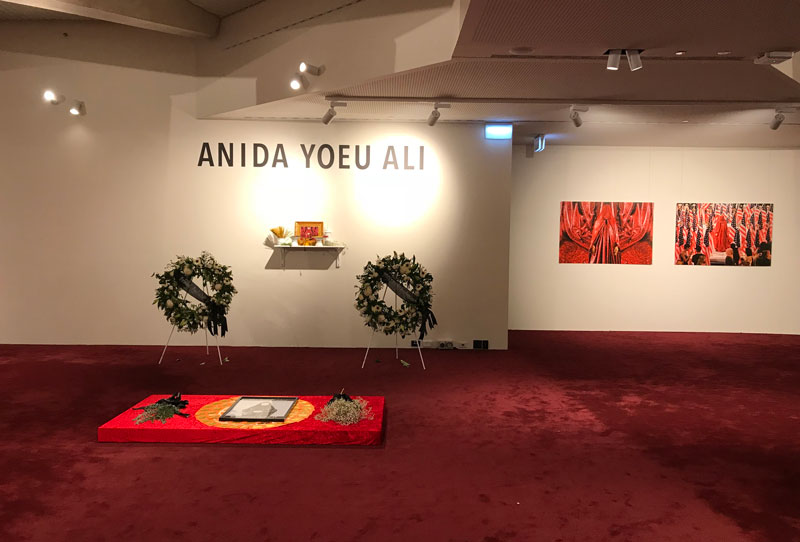

At the Festival Centre the disruption of major reconstruction work, destined to continue into the foreseeable future, has resulted in a new river-facing entrance to the Festival Theatre and the creation of three interlinked temporary exhibition spaces. These run adjacent to the foyer of the Festival Theatre in the area that was formerly the entrance/ticket office and cafe. The interior corrugated cast concrete walls have been painted gallery off-white, and the floor covered in an acreage of wine-red carpet. The result is a space that is half gallery, half theatre foyer. It is not an easy area for art, with the carpet being particularly antithetical to the lolly pink cotton puffs of JeeYoung Lee’s installation. Yee I-Lann’s photographic series suffers, too, from being adjacent to the foyer bar. Anida Yoeu Ali’s rich red installation of fabric, and bold graphic and photo documentation fares better here, to hold its own in this ambient space.

It is a matter of conjecture how many people will brave the circuitous access route past the construction to see these exhibitions during daytime opening hours. I was alone in the galleries during my visit apart from some front of house staff getting ready for the evening performance. Nor was the Festival Theatre programmed as part of the OzAsia Festival, with all festival performance events in the Dunstan and Space theatres. Instead it was the venue for the musical Mama Mia, so the exhibitions will not even be seen by OzAsia theatre audiences. All of which is a great pity, because these exhibitions are certainly worth seeing.

Cambodian-born and raised in Chicago, Ali’s previous body of work, The Bug, was shown at the last Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane. In these and other works of recent years, she has built a global following through her confronting performances challenging prevailing perceptions of Muslim women specifically in relation to their customary apparel. Ali’s The Red Chador: In Memoriam was an exhibition commemorating the metaphorical death of her performance avatar, The Red Chador. We were informed via an Obituary in a printed broadsheet that “The Red Chador disappeared December 2, 2017 and was last seen at Ben Gurion Airport (Tel Aviv, Israel). Memorial services to commemorate her life will be held in Philadelphia, Phnom Penh and Adelaide.”

This real incident in Ali’s life when her work was confiscated in transit on exiting Israel was a transformative event in the artist’s project, here made the central premise of this final memorial act. At the exhibition’s opening Ali read a lengthy eulogy and performed a brief Muslim/Buddhist ceremony with incense sticks at an altar-style installation. Attendees of the opening event were invited to light and lay incense at the altar in memory of the vanished Red Chador. This required perhaps more engagement with the artist and her project than many of those attending were prepared for on first encounter.

.jpg)

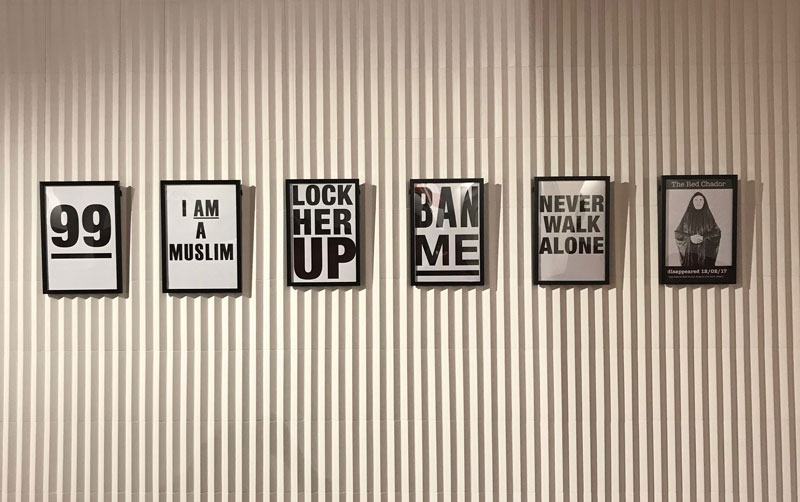

The strength of Ali’s performance work was apparent in the video of her performance of The Red Chador in Washington DC. Here she is shown in an alcove, surrounded by a cluster of American flags. Her body is completed covered, except for her face, by a red-sequined chador. She is in a public place and curious members of the public pass by, take photos and occasionally interact with her. She reacts with minimal gestures but does not speak. It is a brave act to humanise her as a Muslim woman in the face of generic typecasting by the mainstream media. In one of the still images, she stands on a public street in the red chador holding a placard BAN ME as curious passers-by appear confused and possibly threatened. Much of the exhibition consisted of framed graphic slogans, based on placards used in Ali’s performances and juxtaposed with still images documenting these performances. This use of slogans was reminiscent of 1960s anti-war, agit-prop street theatre. Further examples of this printed in stark black and white capitals, read: I AM MUSLIM, LOCK HER UP, BAN ME, NEVER WALK ALONE, followed by a framed image of The Red Chador. Overall, this exhibition was limited by its reliance on such remnant documentation and lacked the full impact of the real-time events.

Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann, studied art at the South Australian School of Art in the early nineties before returning to live in Kuala Lumpur. From her base there she has built a substantial reputation through participating in biennales and major survey exhibitions in Indonesia, Australia, Amsterdam, Singapore, Germany and Japan. Her photomural for Oz-Asia had the enigmatic title, Like the Banana Tree at the Gate. It comprised a sequence of images of young women with their faces obscured by long black hair cavorting amongst banana plants. As the exhibition information sheet explained, the title took its inspiration from two ubiquitous indigenous motifs in I-Lann’s native Malaysia – the banana tree and the vengeful female spirit with long black hair who is associated with the banana plant. In a further helpful interpretation, it is said that “Yee captures the potency of female power derived from local knowledge and folkloric traditions …” As has been elsewhere shown, this artist’s work is focused on picturing and representing self-empowerment. From an Asian cultural perspective it also brings to mind associations with the cult Japanese videodrome films of the long-haired malevolent female protagonist in The Ring. It remains an enigmatic work, whose elusive meaning was only partially elucidated via the text note.

South Korean artist JeeYoung Lee, whose work was featured in the festival’s promotions, created work of a much more spectacular dramaturgy and optical intrigue. Within the confines of her tiny studio in Seoul, Lee constructs enclosed room-like sets based on her dreams and memories, and then photographs herself within these settings. Playing with scale, perspective and colour she creates an Alice-down-the-rabbit-hole world in which she is an adventurer insider her own psychic landscapes. It is not surprising that on social media within a certain younger demographic she has developed a strong fan-base. The screen images were enlarged to mural prints for OzAsia and complemented by a new installation, Secret Garden, devised for the Festival Centre. A deep green four-poster bed was set amidst a “cotton candy” field of pink cotton wool flowers. The artist stated in publicity material that this was inspired by the beauty of the Australian landscape, which somewhat stretched credulity as it would be hard to find anything less like an Australian landscape, with its candy-coloured indoors artificiality.

This generational obsession with social media as the message was driven home in the theatre work, Here is the message you asked for … Don’t tell anyone else;-) by Chinese director Sun Xiaoxing. In this production, the stage was dominated by a scaffolding set of four sleeping pods and surrounded by pillows for members of the audience interacting using their mobile phones. Four young women actors lounged in their separate sleeping pods, each immersed in their media worlds, frantically working their phone and computers to generate a bombardment of imagery that was projected on translucent fabric screens hung in front of each pod. By way of distraction, some of the time, three musicians churned out ear-splitting electronic post-rock noise. Overall, there was limited interaction beyond incomprehensible chatter in Mandarin. While half the audience were also working their mobile phones to interact digitally with the four girls, the other half, like me, sat entranced by the sheer inscrutability and ceaseless momentum of this internalised activity. Rarely have I seen such an intriguing piece of theatre. Subversive and cautionary in its message, it doubled much of the visual arts program, including the extraordinary data projection work of Ryoji Ikeda in the Festival Centre Artspace to reinforce the invasion of the virtual digital realm into analogue reality.