The creative theme of annual festivals can sometimes become a meaningless marketing jumble. Not NAIDOC Week 2018. “Because of her we can” has been a clarion for programming and reflection. None better than the pair of exhibitions presented at the Canberra Contemporary Art Space by Brenda Croft and Amala Groom. These installations made by women, reflecting on their relationships with other women and the legacy of their influence, speak to the complexities of cross-cultural and cross-generational communication.

Entering the space the visitor first encounters the work by NSW-based artist Amala Groom, originally commissioned by Casula Powerhouse in 2017, consisting of a multi-channel video work of talking heads and a small painting by Emily Kame Kngwarreye. The two key elements of the installation, on opposite sides of the space, are placed together in dialogue by a third element – the line of text on the adjacent wall that is the clarion for the show – “does she know the revolution is coming?”

Each of the characters in the video, played by Groom herself, are acutely observed hyper-real characters, realised through their clothes, their patter – as society ladies – represented coifed and preening, sipping on champagne and boasting of their art collection, alongwith the artist herself, just as glamorous, playing host. The layering of dialogue flowing back and forth is based on the artists’ experience of attending a social event as a delegate of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York, only to be told by an affluent collector and wife of a previous prime minister that “have you seen My Emily.” For the artist, this misplaced assumption that ownership equals possession, triggers a wave of disgust at what she sees as the fake altruistic empathy towards indigenous peoples and the disconnection between the reality of lives led by many of the artists and those who own their art.

The real Emily, loaned from a private collector, sits quietly opposite. Its precious physicality is a reminder of the cultural power embodied within.

Complementing this act of appropriation, in an age when downsizing and de-cluttering is a virtue, and where we are extolled to hold onto only those things “which give us joy,” we can be grateful that Brenda Croft has ignored such advice. She has gathered and collected her mother’s things, packed, sorted and unpacked them again to present a retelling of a life that is both a sad memorial and joyful celebration.

Tender rather than dispassionately forensic, Croft’s presentation of Hand in Heart (2018) at the Canberra Contemporary Art Space permits the voice of her mother to speak through the things she has made, the photographs she took and the things she collected. Presented with dignity and care, the installation is not just a portrait of one woman’s life but a reflection upon a generational experience of twentieth-century Australia.

The accompanied catalogue – which can be viewed in full online – features a text by the artist along with an insightful short essay by CCAS Director, David Broker. Croft’s writing is purposeful, honest and unflinching, revealing a life story of a woman who grew up in Hurstville, Sydney, but broke from convention to pursue employment on the Snowy Mountains scheme, found unconventional love with an Aboriginal man, then marriage and children. Her text also reveals the testing intimacies of a mother and daughter relationship and the profound sense of loss at her passing. Croft clearly aches in a poem, which is also included in the catalogue:

… forty-nine years ago I emerged

after a two-day battle

back to front as has always

been my want

the battle continued for the next

forty six years

back and forth, love and hate

anger and hurt, sorrow and joy …

Brenda L. Croft, 17 March 2013

But the catalogue text is for later. The pleasure of this exhibition is to take the time to absorb the selective gestures that the artist has made and the threads that connect the life story together. The generous scale of the CCAS exhibition space at Gorman House allows for the seven distinct works as installations of objects and images to each have their own presence and visual clarity. In previous photographic series, such as In My Mother’s Garden (1998), Colour B(l)ind (2000) and more recently Blood Type (2016), Croft has layered text upon images. Here the intervention is in the selection and arrangement – a process that sits between the implied distance of a curatorial practice and the intimate hand of artistic creation.

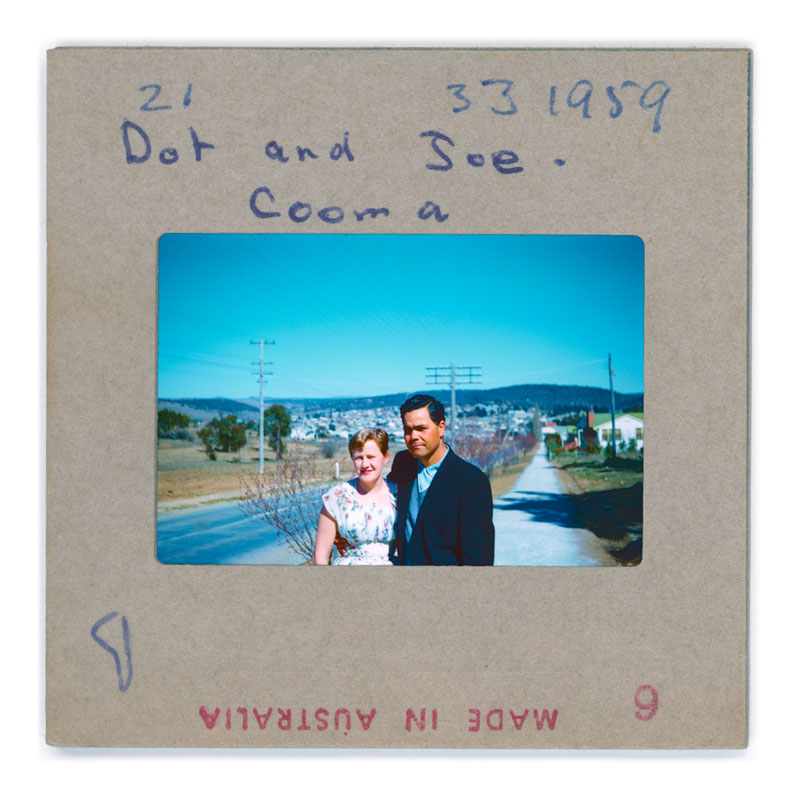

Dominating the main exhibition space are the series of enlarged Kodachrome slides as the visual backdrop to the exhibition. Although well aware of her mother’s photographs, Croft only recently discovered this group amongst her grandparents’ things as these were the particular images that Dot had pulled out, annotated with cheery captions. In this installation, there are shelves loaded with a woman’s life of pretty things, hard-won or patiently made: including dainty handbags, petite figurines, children’s dolls, and Dot’s camera, safe in its slightly battered leather case.

home-made 2018 on the adjacent wall, features paper ephemera arranged with the care of an archivist in plastic sleeves, but with the colour eye of an artist. Standing back from the grid, a palette of pale pink, cream and pale blue predominate – up close they become the cards for “It’s a girl,” congratulatory telegrams and pay slips; officialdom alongside the most fragile of scrawled notes.

The presentation of this work in Canberra, and in this specific location within the old Gorman House, brings further resonance to a reading of the work. There is the echo of its own history as a hostel for unmarried public servants, which parallels the story of the subject itself, for Dot lived in similar accommodation in Cooma. In the photographs there is the image of Canberra and the nearby mountains – the vivid blue sky, the leaves just about to turn an autumnal blush, the open road and views to the ranges and all the limitless possibilities that are suggested by this record of their love captured in a specific time and place.

At a deeper level there is is also a story of lives played out quietly in this heart of the nation, that reveal some of our greatest tensions; a story of lives impacted by stolen generations, the assertion of women’s independence and the breaking of class and racial barriers. In a side space of the exhibition Croft invites us into a small living room of memories, to sit and listen to a soundtrack blur of TV and radio, comforted by Dots own vividly patterned crochet rugs to prompt further reflection.

Both artists, Groom and Croft, carry a deep sense of responsibility towards their families as well as to the wider community and clearly build their practice upon a trusted dialogue with elders. The NAIDOC 2018 Theme “Because of her we can” is especially resonant here, for both Croft and Groom in honoring the women that have come before them – specifically, Dot and Emily – build their own foundations for others to follow.