As a public act, to walk is to be exposed to the world, to be outside in nature, culture or both. This idea—how we privately navigate public space—is central to From Here to There: Australian Art and Walking, at the Lismore Regional Gallery. Conceived by locally‑based independent curators Jane Denison and Sharne Wolff, the exhibition features twelve Australian artists for whom walking is a key part of their processes. In the accompanying catalogue, artist statements by Sarah Mosca, Noel McKenna and Alex Karaconji all overlap in acknowledging walking as a strategy of “slowing down” the world, exemplary of this exhibition’s focus on artists who register observations that others might take for granted.

Because it requires open spaces, the where and why of walking is embedded in a certain spatial politics. In the eighteenth‑century cities of Paris or London, for instance, the idea of walking for pleasure, outside of private gardens or squares, was largely unheard of before the 1760s. Public spaces lacked pavements, and streets were filthy. Following the first legislation for paving and maintaining London streets in 1762, similar laws were enacted throughout Europe. It was in this period that the ability to walk gracefully in full view was central to the very concept of the public sphere, where participants could adopt the role of the moral citizen and, according to Adam Smith, convey a sense of decorum “distinct from the perception of utility.”

In response to this shift in the perception of public space, Denis Diderot, the first art critic, treated eighteenth‑century Salon paintings as if they were three‑dimensional environments, describing works in precise detail as if actually walking through them with his readers. The next century, Charles Baudelaire’s flâneur became paradigmatic of the modern artist, observing the busy crowds of Paris as if they were a form of theatre. From this infamous dandyesque figure—which now borders on a masculinist cliché—what followed was a host of ambulatory tropes that entered into art history, in the form of plein air painting; Guy Debord’s dérives, Bruce Nauman’s studio exaggerations; Eleanor Antin’s 100 boots; Richard Long’s minimalist landscapes; Emily Kngwarreye’s ancestry journeying; and Zoe Leonard’s peripatetic conceptualism, to name just a few.

Despite the profusion of art-historical imagery associated with walking, From Here to There only scratches the surface when it comes to the political implications of this at once simplistic and substantial topic. Looking past the overly ambitious nationalism of its title, the strength of the exhibition is its focus on the intersecting processes of its artists. Each provides a written statement in the catalogue, which is repeated on wall plaques adjacent to their work. From this we learn that Daniel Crooks is fascinated by the speed of how we walk, whereas Sydney artist Nell takes inspiration from the knowledge that no journey would be possible without taking the next step.

Nell’s installation A white bird flies in the mist, a black bird flies in the night, a woman walks, wild and free, she is not afraid to die (2008), is the first piece encountered in the exhibition, which is spread across two galleries in Lismore’s slick new building (unveiled in October 2017). The work comprises 33 glass sculptures that, nostalgically, evoke the form of the Pac-Man ghost, positioned on a low plinth on the floor of the gallery. They appear to trail behind a naked, life-size woman holding a walking cane, rendered in blackened bronze. The figure, whose eyes are filled with iridescent white pearl, recalls Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) by way of the neo-pagan feminist sculptures of German‑born American artist Kiki Smith. A pastiche of naturalist, Christian, pop-cultural and Romantic references, the title like the work itself, comes off as a slightly off-kilter expression of urbane spiritualism.

Whereas the tableau-like quality of Nell’s contribution takes it into the vein of a fairytale illustration rather than a piece about movement, Lauren Brincat’s durational performance captured on video demonstrates how walking can be a mapping of space and time. Walk the Line (2016) is a five-minute video that takes place at Cape Leeuwin, Western Australia. In the first few seconds, the artist’s hand is shown up close making sounds by being swiped across the surface of various rocks before revealing the artist at a distance, traipsing across dunes. Then, moving away from the camera, Brincat is seen walking in a straight line towards the ocean, eventually disappearing under its surface. We learn from the wall plaque that the artist traces the topographical demarcation between the Southern Ocean and the Indian Ocean. More interesting is the actual structure of the work, which has an ambient soundtrack throughout yet starts as a type of percussion piece, appearing increasingly melancholic as the artist—wearing what looks to a be a full-body leotard—fades from view.

To “walk the line” usually means to conform to an established moral code, made famous by Johnny Cash. In Brincat’s hands, this clarity around responsibility is shown to be at odds with the relatively arbitrary mapping of two different oceans. Such ambiguity is present in much of Brincat’s work, who applies Paul Klee’s account of drawing as “taking a line for a walk” to the realm of video and sound art. Recalling the vernacular minimalism of British artist Ceal Floyer, in many of Brincat’s short, easy‑to‑watch videos, she plays out an idea within very specific everyday contexts to see what eventuates. In This Time Tomorrow, Tempelhof (2011), Brincat follows the broken white lines of Berlin’s now defunct Tempelhof airport, and is shown disappearing from view as if dissolving into the formalist registers of her work—a trope that repeats throughout her practice.

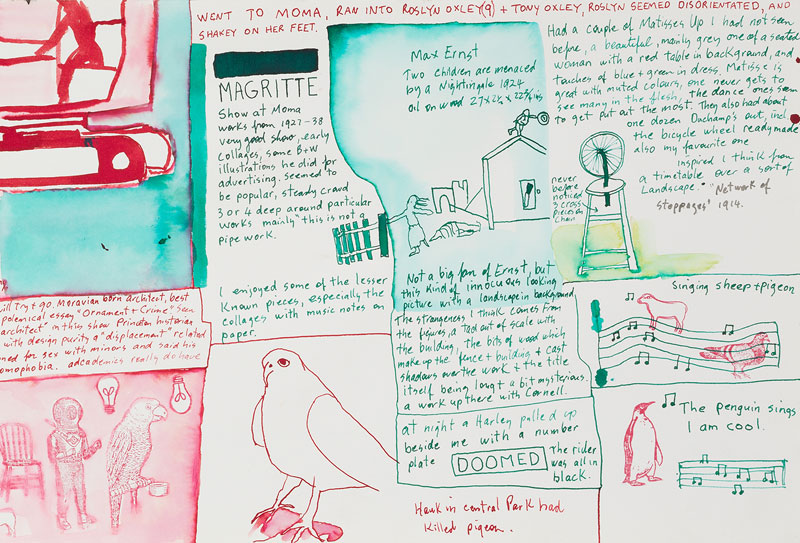

As one of Australia’s foremost roving artists, Noel McKenna is perfectly suited to this curatorial rationale. His work centres on observation and, to a certain extent, connoisseurship, looking not to any standards of taste but to what compels him from moment to moment, as his Instagram account makes clear. Although four of his oil‑on‑plywood works are included in the show, the scrutinising quality of his practice is most noticeable in 14 Days in New York (2013), comprising thirteen diary pages of drawings and notes from the artist’s sketchbook. Walking around New York is one of the genuine luxuries in life. McKenna is lucky enough to have turned it into a routine of sorts, filling his diaries each year with unplanned observations that may find their way into his more nuanced pieces, as they did in his 2016 exhibition, Seltzer, at Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney. 14 Days in New York is filled with numerous whimsical drawings and artworld commentaries, such as a photograph of an iron by Man Ray encountered at a private gallery on Madison Avenue, as well as the reflection: “Went to MoMA, ran into Roslyn Oxley(9) and Tony Oxley. Roslyn seemed disorientated.”

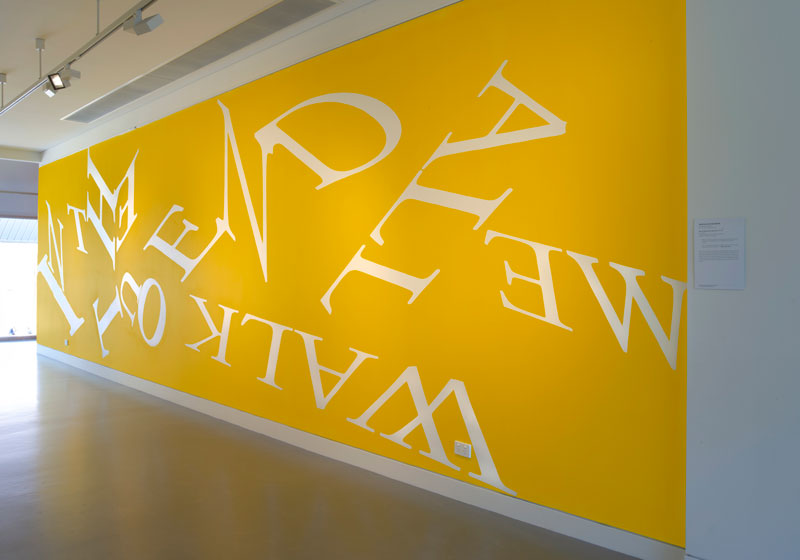

Outside the main space, Agatha Gothe‑Snape’s wall painting, We All Walk Out in the End (2012/18), emblazoned its title on the wall running from right to left, presenting reversed and oddly‑sized classical lettering on a gorgeous yellow ground. Originally designed for the huge entrance wall in Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art in 2012, the painting does not work well here, offering no perspective and no reason to walk around it. Its puzzling equation of dying with walking out of the room is curiously self‑affirming, but perhaps limited by this emphasis on human agency. As Paul Keating famously said to Julia Gillard: “We all get taken out in a box, love.”

Rebecca Gallo’s hanging assemblage of found scrap objects, An Irregular Dancing (2016), and her flip book of photos taken on her wanders around Lismore, Walking Lismore (2018), help to give the exhibition a local connection. Gallo makes work from found rubbish but, thankfully, rejects the impulse to transfigure her materials. It rounds off what is a notable array of distinct Australian works at the Lismore Gallery, whose exhibition programming, under the directorship of Brett Adlington, has been self-consciously inoffensive in recent years, geared so much towards the senior members of our society that it has provided little inspiration for experimental and emerging artists from the local area. Here’s hoping From Here to There is a sign of things to come.