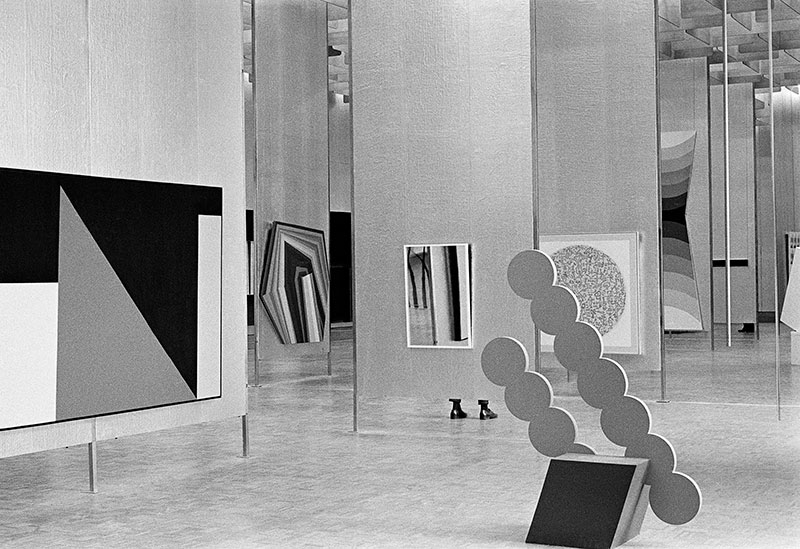

What’s left to be said about The Field? Actually, quite a lot, as already the most discussed art show since at least the famous 9 x 5 Exhibition that took place just down the road some 130 years ago. Indeed, as I write this, it occurs to me there is a whole thesis out there waiting to be written on The Field (although that’s already been done). There are any number of things we could find out that would help us better to understand the show. First of all, it was said to be a time of Australian provincialism – it always is – so the question will revolve around who knew what when. How closely were the artists and curators, but more importantly in this case the critics and commentators, following events overseas? What kinds of visual vocabulary did they possess? What types of distinction – aesthetic, but also perhaps between the aesthetic and the non-aesthetic – were they capable of making?

1968 was a big year, and The Field a controversial show, but we have to look closely at both the year and the controversy. The Field was controversial, although Patrick McCaughey in a recent article for the NGV rehang says it was not.[1] And, in some ways, as we will see, he is right. (In passing, it is amusing that a gallery like the National Gallery of Victoria that is so keen to discourage critical discussion of their program today is happy to hype a show it once put on because it was controversial.) But I would say that the true nature of its controversy was missed or misunderstood at the time. Of course, it is always seen to have drawn a line between the national and the international, the figurative and the abstract. And to this extent it can appear unified, unified even against the apparent differences between the works, as in the well-known characterisation of the show by Ian Burn and Nigel Lendon as ushering in an “institutionalised avant-garde” as though it were some overall “avant-gardeness” of the work, or its overall “institutionalisation”, that was at stake.[2] And, as though it were effectively a matter of The Field versus the rest.

But I’d rather suggest that The Field is in controversy with itself, and even that there was a controversy between the two named curators of the show, John Stringer and Brian Finemore, a controversy that perhaps only became clearer later when Finemore put on what I think can only be understood as a riposte to The Field, the 1973 exhibition Object and Idea, also at the NGV. Here is the first task for any new historical research into the show: what was Stringer and Finemore’s relationship? Were they even on the same page during The Field? It is always assumed that Stringer was the principal curator and Finemore, as head of Australian Art in the Gallery (astonishingly, the first time such a position had ever been created in any Australian State Gallery), was merely the official representative. But, for all of Stringer’s much-touted time overseas in America before the show, where he was to return after it, was Finemore in fact better informed about what was happening overseas? It is certainly possible, as future events will bear out. Undoubtedly, part of the dominance of Stringer in the reception of The Field is the effect, I’d propose, of the fact that Finemore was murdered in an unsolved gay hate-crime in the mid-1970s, soon after Object and Idea, and so was not around subsequently to put his side of the case.[3]

And this brings me to the second matter: 1968. Amongst all of the things that happened around the world in 1968, I might just mention two: the exhibition of the Mary Sisler Collection of some 78 Duchamp works at the NGV in February and Clement Greenberg’s inaugural Power Lecture, “Avant-Garde Attitudes: Art in the Sixties”, at the University of Sydney in May. Starting with the second, “Avant-Garde Attitudes” is the lecture in which Greenberg – prophetically ahead of his time – decries what he calls “post-modernism” for its refusal of aesthetics, its passing over of art for the realm of ideas. Of course, by this time Greenberg was getting on, and his is a weak even dispirited defence of modernism, drawing obviously on the work of the protégé who had now split with him, Michael Fried, who the year before had published his canonical attack upon minimalism and its “theatricality” in the essay “Art and Objecthood.” And, as explicitly stated by Greenberg in his lecture, but beneath even mention in Fried’s essay, before minimalism was Duchamp, whose work had extensively toured Australian galleries the same year as Greenberg’s visit, as though in friendly rivalry.

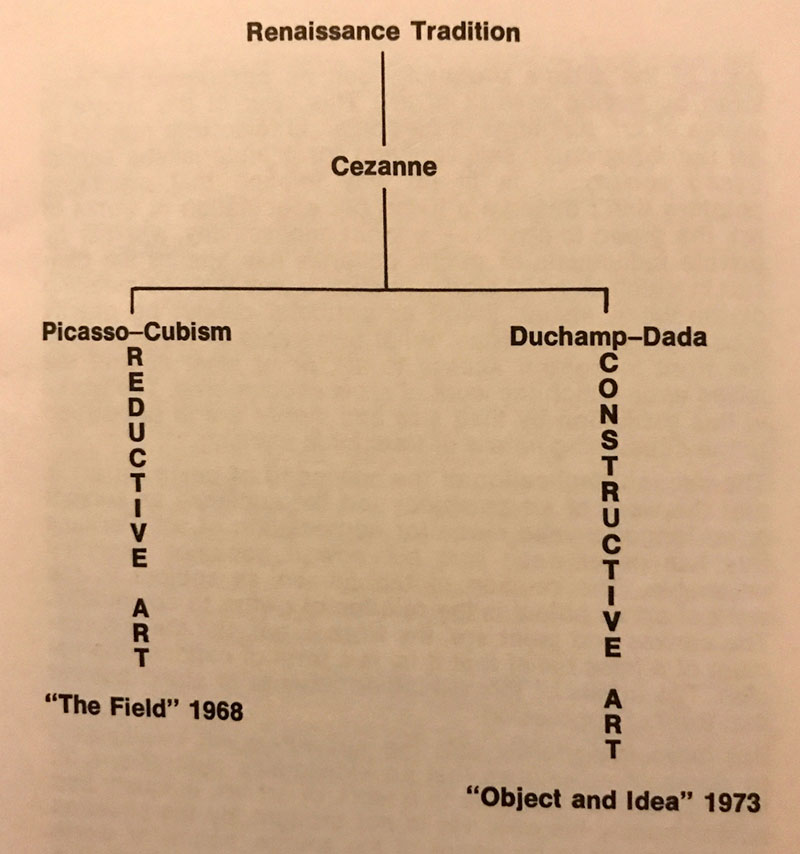

What is all of this to suggest? Not that the artists in The Field were across the emerging modernism–Duchamp/minimalism split (because artists don’t necessarily think like this). Nor even that the curators were across it (although it was the express subject of Finemore’s later Object and Idea, as the remarkable diagram showing the split after Cézanne into the two opposing sides of Picasso–Cubism and Duchamp–Dada reveals). But it is surprising that in the numerous reviews of the show at the time, both in newspapers and art magazines, it is not mentioned. And it is even more astonishing that it has not been mentioned in any of the subsequent restagings or academic commentary, given the later evidence of Finemore’s true feelings towards the exhibition. The Field is seen as a unified (if finally socio-historical) phenomenon in the essay by Burn and Lendon for Heide’s The Field Now in 1984. In the catalogue for Fieldwork at the NGV in 2002, it is admitted that the show is disparate, featuring hard-edge painters, minimalists and conceptualists, but this is seen merely as successive waves of avant-gardes, as though coming before and after the show, without seeing how each is simultaneously present in the show, dividing it from itself.[4]

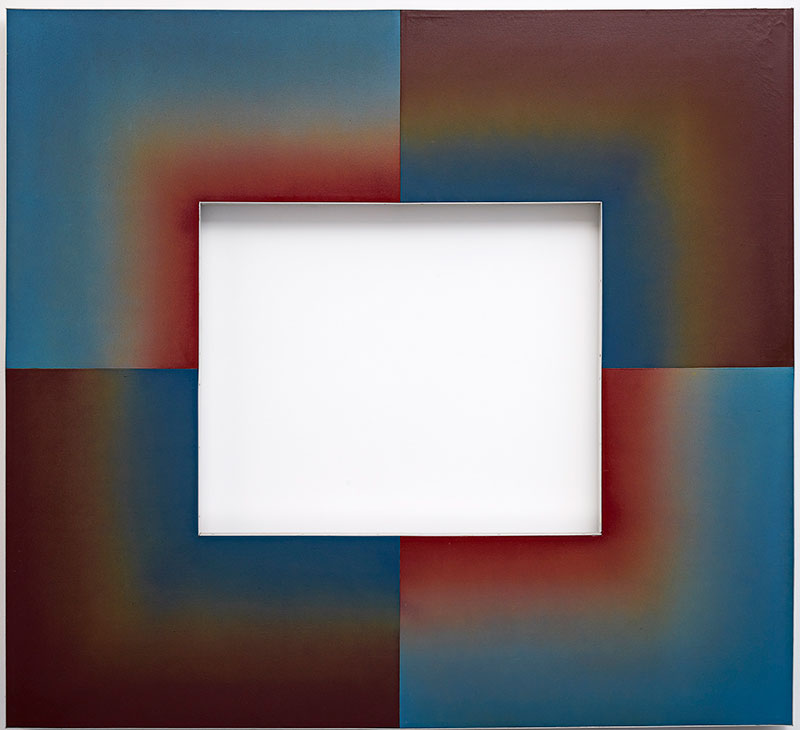

For the truly uncanny thing about The Field, looking at it now – but precisely the point is that it would also have been possible to see back then, although no one apart from Finemore did – is that a kind of invisible line can be drawn through it, placing works on either side of it and separating the show from itself. On the one hand, we have such obviously colour-field or hard-edge painting as David Aspden’s The Field(1968), Syd Ball’s Ispahan(1967), Michael Johnson’s Chomp(1966) and Tony McGillick’s Arbitrator(1968). There is also the modernist Caro-influenced sculpture of Col Jordan’s Knossus II(1968) and Clement Meadmore’s Up and Over(1967). Then there is painting that because of its over-symmetry or lack of compositional dynamism is something like minimalism: Dale Hickey’s Malvern(1967), Trevor Vickers’ two versions of Untitled(1968), Ron Robertson-Swann’s Orange Oriel(1965) and even Janet Dawson’s Rollascape 2(1968). There are line-ball minimalist sculptures like Tony Coleling’s Untitled(1968), the one with the long horizontal pole straddled by thin back wires, and Nigel Lendon’s Slab Construction(1968), which for all of its white brick-like anonymity still has aspects of contrapposto. Then there are the clearly minimalist paintings – though, of course, to put it this way is a contradiction – like Mel Ramsden’s three-metre-long untitled black panel and the clearly minimalist sculptures, like Wendy Paramor’s Robert Morris L-beam-inspired Luke(1967) and Tony Coleing’s other works, and finally what can only be described as readymades: Mike Kitching’s Phoenix II(1966), and perhaps Burn’s Two Glass/Mirror Piece(1968).

None of the original catalogue essays by Patrick McCaughey, Royston Harpur and Elwyn Lynn (well, maybe Lynn a little) mention the obvious discrepancy between the various works in The Field, even though catalogue writers are meant to be up-to-date (as opposed to artists and curators, who necessarily develop their projects over years). And this goes even more so for the then-contemporary commentators on the show, both in Melbourne and later when it travelled to Sydney. By 1968 there is a lot of evidence that the Duchamp/minimal/post-modern alternative was visible and able to be discussed. In fact (and remember the time-lag for curators), it was just this split between the two halves of The Field that Finemore was soon to make a show of. Here would be another suggestion for further research on The Field: to trawl through all of the critical literature concerning the exhibition and all of its curatorial remakes over the years to see whether this alternative is ever elaborated. For it is evidently the dialectic driving the original exhibition, the debate it is having with itself.

Put simply, the real question spectators ask themselves today as they wander through The Field is: are all the works in it the same? Are they all paintings and sculptures, or are they something else? Are they all to be understood within a modernist paradigm (which is still a pretty powerful explanation of what we are involved in here) as works of art? Is Coleing’s Untitled the same kind of thing as Meadmore’s Up and Over? Does Kitching’s Phoenix II really belong in the same show as Johnson’s Chomp? (Along with the question: why the hell didn’t someone clean Johnson’s Chomp?) And, moreoever, to not even consider that spectators would have been thinking the same question back then (or, indeed, artists, curators and critics) is just to make us seem provincial. And we have never been provincial.

So what about the rehang of the original exhibition in 2018 as The Field Revisited? It arrives as a sort of tautological endpoint to an almost endless series of curatorial remakes and rebootings over the years (The Field Now, Fieldwork, Tackling the Field, After the Field, Returning to the Field)? Amongst one of the implicit meanings of its literal restaging and the attempt to include as many of its works as possible is the assumption that it was all originally one exhibition and that all of these works in some meaningful sense belonged together. But I would argue – and I would generalise this to all cultural objects that “live on” – that the long-running fascination with The Field, the reason why successive attempts to remake it continue to be undertaken and why each is seen to fail to solve the problem, is because the show is not one, but divided from itself. In other words, the works of art are arguing amongst themselves. So that, in effect, we might offer a critique (or a remake) of one part of the show only in the name of another part of the show. It is how we might imagine this remake: not simply as a slavish reproduction but opening up the opportunity to think how the original exhibition did indeed constitute a certain turning point. Not so much between nationalism and internationalism or figuration and abstraction, but between abstraction and itself. It would be as though it offers us a chance to imagine – and my point is this is actually true – that what we can think about it now was also available to be thought back then. Not 1968 remade in 2018, but 2018 as it were inserted back into 1968.

The curation and the catalogue essays for The Field Revisited largely fail to do this. The closest they come to this interpretive point is in David Homewood and Paris Lettau’s suggestion that we can imagine the installation of the show as somehow cutting against the works in it. That its installation – the floor-to-ceiling screens, the choice of silver wallpaper to cover the walls of the exhibition – creates an “environment” that contradicts the formalist autonomy and compositional self-containedness of much of the work: “Like a pop environment or a minimalist installation, The Field’s silver walls activated the space around the work of art, heightening the spectator’s awareness of their movement around and through the exhibition space”.[5] And this is undoubtedly true. But what is perhaps missed – or maybe what I am saying is ultimately only an extension of their argument – is that it is a matter not so much of the show versus the works as of the works versus themselves. In other words, Homewood and Lettau make the point that the all-encompassing design of the original exhibition undermined the autonomy of the modernist paintings in it while following the “theatricality” of a number of the other works (for example, Paul Partos’s Vesta II, 1968). But their argument could have been abbreviated simply to point out that there were two radically different types of work on view.

McCaughey writes in his retrospective preview of the rehang that the original Field was “superficial”, but it is arguably superficial not in the way that McCaughey himself sees. It is superficial not because it mixes works of “unequal quality”, but because, whether consciously or unknowingly, it brings together two profoundly different categories of work: modern paintings and sculptures and post-modern works of art. And, as can be seen, the critics and commentators at the time would absolutely have had the resources to realise such a distinction (the visit of Greenberg defending modernism against minimalism, the Duchamp show, even the touring Two Decades of American Painting on at the NGV in June 1967, which year was already a turning point in post-War American art). But they didn’t, and it would have to wait until Finemore published his mea culpa with Object and Idea some five years later. In not making something like this the subject of the show in its rehanging, we can still speak of The Field as superficial, this time with regard not to its curation by Stringer and Finemore in 1968 but its curation by the NGV in 2018. Nothing has been seen, nothing has been learned, in fifty years. We still remain provincially blind, but this time to ourselves.

Footnotes

- ^ Patrick McCaughey, “The Field at 50: NGV Restages the Show that Changed Australian Art,” Sydney Morning Herald, 21 April 2018, p. 20: https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/the-field-at-50-ngv-restages-the-show-that-changed-australian-art-20180419-h0z06p.html

- ^ Ian Burn and Nigel Lendon, “Purity, Style, Amnesia,” in Sue Cramer, The Field Now, Heide, Bulleen, 1984, p. 21.

- ^ There is a terrific website dedicated to such crimes, and the possible police involvement in them, or at least their manifest lack of interest in solving them: http://www.josken.net/hateaus1.htm.

- ^ As co-curator, Charles Green writes: “colour-field painters … out of step with the late 1960s; minimalists already escaping field painting … conceptualists who fiercely dismissed both abstraction and minimalism as old-fashioned and irrelevant,” in ‘The Discursive Field: Home is Where the Heart Is,’ Charles Green and Jason Smith, Fieldwork, NGV, 2002. p. 12.

- ^ David Homewood and Paris Lettau, “Hall of Mirrors,” in Beckett Rozenthals, The Field Revisited, NGV, 2018, p. 93.