Inside the massive shipbuilding warehouse on Cockatoo Island lie the two biggest works of the 2018 Biennale of Sydney. One is Ai Wei Wei’s Law of the Journey (2017), an inflatable refugee boat that stretches into the cavernous depths. The other is Yukinori Yanagi’s Icarus Cell (2018), a corridor of sea containers and mirrors that leads to vertigo and disorientation. Apart from their scale, these two works have nothing in common, the first political and the second poetic. Their juxtaposition begs the question as to what this particular biennale is about, or whether this is still the right question to ask. Curator Mami Kataoka explains that her choice of theme, Superposition, is:

… a quantum mechanical term that refers to an overlapping situation. Microscopic substances such as electrons are said to be dualistic in nature: they paradoxically exist in the form of waves and granular particles simultaneously. The state of superposition can be applied to all conceptual levels—different climates and cultures; views of nature and the cosmos; perceptions of Mother Earth and land ownership; readings of the human condition over centuries; the history of modern and contemporary art.[1]

While this sounds like a handy rationale for explaining everything and nothing at the same time, it is also an attempt to give some shape to the ambition of the biennale format today. Biennales are expected to do nothing less than configure the world within an exhibition, to channel the global Zeitgeist with a representative range of artists and artworks. It is no wonder that Kataoka defers to abstract concepts and doublings, and here she is not alone. Perhaps the most successful curator working today, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev also deferred to quantum metaphors to explain her 2008 Sydney Biennale.[2] Her theme was just as vague, Revolutions – Forms that Turn equally undertood to be “turns that form,” as if the one were equivalent to the other.[3] Revolution becomes its opposite, as “The first turn collapses (is over-turned) into the second,” into a “rotation, confusion, revolt, insubordination, anarchy and disruption of order.”[4] So that in 2008 it was revolt not revolution, in a superposition of the avant-garde with Aboriginal histories, northern with southern hemispheres, the past with the present.

The conundrum here is that with such overarching, interchangeable metaphors of overlapping (2018) and rotation (2008), connectivity (2018) and relationality (2008), it is difficult to conclude what mark any one biennale might make, and how to distinguish one from the other. The biennale format has dissolved into its own sufficient contemporaniety, into being “with time” (Christov-Bakargiev).[5] And just as we cannot see quantum scale electrons it is impossible to fully grasp our own historical world, which is necessarily too vast to capture in any one exhibition.

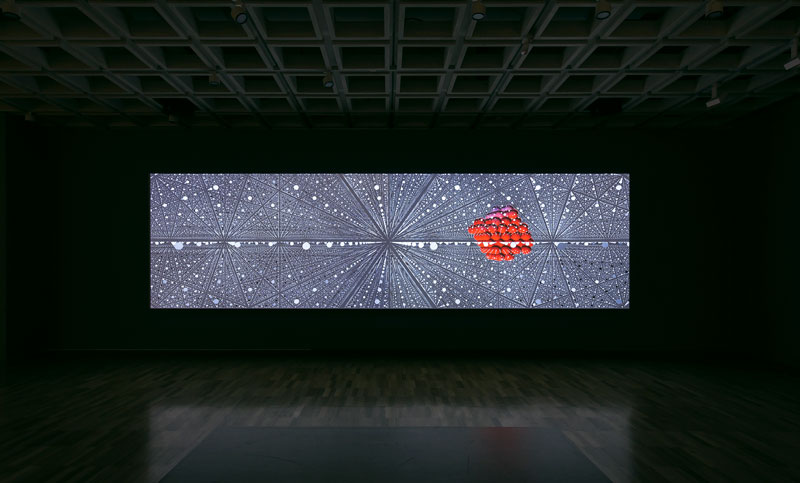

Kataoka goes further than this to argue that Superposition is not only a curatorial premise, but one that lies within the works themselves – that her chosen artists “reflect multiple and sometimes opposing perspectives within their work.”[6] And it certainly appears this way when reading the didactics, or listening to the artist's talk. Lili Dujourie’s sheet of steel leaning on a red wall is actually a condemnation of American Imperialism (1972/2018), while Semiconductor’s Earthworks (2016), a spectacular installation of pulsing patterns of light, turns out to be a modelling program drawing from geology and corporate history. Michael Stevenson’s classrooms of obscure relics and scribbles are reconstructions of New Age classrooms from North America (Serene Velocity in Practice: MC510/CS183, 2017), while Nicholas Mangan’s beautiful video of swirling fragments is actually a “meditation on the conflicting interests of capitalism, climate change and the global economy” (A World Undone, 2012). Such heavily researched, quasi-scientific fictions add up to more than what they at first appear to be, and in the Carriageworks venue in particular the works cohere into an abstract sublime, one that is tied to rhetorics of anti-capitalism and high-tech New Ageism.

But it is to a different strand of work that I turn to in order to flesh out Kataoka’s interest in this kind of complexity – a series of video pieces about exile in the greater Asian region. Beautifully hidden among the Ming dynasty bronzes and Qing dynasty porcelains in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Francisco Camacho Herrera’s video Parallel Narratives (2015–17) spins real life stories of fleeing communist China alongside an ancient Pacific trade in jade and red pottery. History and science come to suggest new possibilities as both turn out to consist of the most unlikely of scenarios. So too, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chia-Wei Hsu’s Ruins of the Intelligence Bureau (2015) tells of a secret Chinese nationalist intelligence village in the north of Thailand, where soldiers were marooned without a country through the twentieth century. Videos about Chinese nationalists fleeing communist China to Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand recur across venues in outlandish yet-true stories of hoaxes and narrow escapes. Across such lines of exile it is possible to appreciate Kataoka’s quantum metaphors for the way they describe this bringing of the invisible into view, and yet whose totality will always disappear into complexity.

video installation. Courtesy the artist and Liang Gallery, Taipei. Produced by Le Fresnoy

It is with this in mind that we can also understand why there is no need for a 2018 Biennale catalogue. While there is a good argument that a catalogue would have a better spend than Ai's overblown boat, it may well be that authoritative, critical records are no longer a necessary part of this new kind of quantum biennale.[7] Catalogues have been on the decline in Sydney for some time. While Christov-Bakargiev's 2008 version included excerpts from philosophers and writers alongside critical essays, by 2016 the catalogue had become a collage, with no critical essays at all.[8] The shift is a curatorial one as the heroic themes of older Sydney Biennales, such as European Dialogue (1979) and Boundary Rider (1993), have given way to more ambitious but also more diffuse themes, such as All Our Relations (2012) and Imagine What You Desire (2014). These are both themes and not themes, a way of capturing the ambition of the contemporary Biennale to be everything to everyone.

Taking the catalogue’s place in the Art Gallery of New South Wales is an archive of the Biennale’s own history. There are old letters and photographs in vitrines, sitting amidst display of posters and videos documenting the excitement of the past. There is also a lecture series from previous curators taking place over the course of the Biennale, in which Christov-Bakargiev herself is speaking. So it is that this Biennale is characterised by a certain self-sufficiency not only on the part of its artists but on the part of the Biennale that here superpositions its own history – its own archive – as critical content. It is easy, browsing the old catalogues that are also part of this archival display, to be nostalgic for the strong curatorial themes, essays and public programs of yesterday, that once positioned rather than superpositioned the biennale in one way or another. But the catalogue and its curatorial criticality were also part of an era in which the event aimed to make sense of international trends for a local audience, a determined attempt to bridge the country’s isolation. This remains a part of the Biennale of Sydney’s mission, but since the coming of cheap airfares and the Internet, Australia can hardly claim isolation. The biennale has instead become a site for the materialisation of modes of art that are already well-documented, have already been witnessed overseas or online.

The shift of this late Biennale format is also away from the Anglophone men who once dominated the curatorial chair. At 2018’s opening events, much was made of the fact that this is the first Asian curator to get the gig, to the point that Kataoka came to identify with her own “Asian perspective,” no doubt having learned of her significance in the event’s longer history. And the selection of Asian artists does turn out to be compelling, most spectacularly in Yanagi’s works on Cockatoo Island, including Landscape with an Eye (2018), a nuclear exploding eyeball that floats in a dark, rusting control room. This and the other Asian works often sat better than works from other parts of the world, such as continental Europe, where they cohered less to the invisible sensibilities Kataoka worked to build from venue to venue.

Of course, this failure is precisely the impossibility of the biennale format, to represent a world that will always exceed such sensibilities. If this format has become too big, is too unwieldy and ambitious, this is because it carries with it the expectations of an older, thematic era of the biennale. Hence the athematic nature of this new, post-critical type of biennale, that consists instead of the superposition of multiple currents, that only the laws of physics might be able to explain. So that next to some of the more satisfying curatorial juxtapositions: Semiconductor’s meditation on crystals (Where Shapes Come From (2016)) beside Sydney Ball’s sketchbooks (1960s–1970s); or Yvonne Koolmatrie’s five stunning variations on Ngarrindjeri burial baskets (Burial Basket (2017)) beside a John Skinner Prout etching of mortuary tables (Mode of Disposing of the Dead, 1874–76) next to such synchronies there lie just as many unlikely collisions. These, such as that of Ai and Yanagi, might make little sense at first glance, but across the venues they become part of a greater series of combinations, a quanta of differences.

In Parallel Narratives, Herrera describes the way a zenith point once helped sailors chart a course to a destination they would never reach, a destination that lies beyond natural and political frontiers. This allows his video to chart a “zenithal affinity” between dimensions in history and science. So it is that the curator turns out to be significant in this Biennale not because of her heroic vision, but because it only through the curator that we are able to imagine an exhibition of this scale making sense. Only the idiosyncrasies of an individual could explain its affinities, its superpositions, but also its points of incoherence. Only because there is a curator behind the variety of work does it become possible to imagine lines of connectivity, quantum uncertainties wavering in the Cockatoo Island breeze. For as artists have come to layer complexity within their works, to accompany their installations and videos with meticulously researched information, systems upon systems, it is necessary to turn to the curator and the exhibition as sites of critical attention, the platforms through which meaning is made from contemporary art. As artists have developed their own sufficiencies of detail, the curator has assumed her place as she who maintains the mystique of art, its ultimate invisibility, receding into exhibitions whose coherence exceeds even the curator’s own explanations.

Footnotes

- ^ See Mami Kataoka, “Welcome to the 21st Biennale of Sydney” in Guide: 21st Biennale of Sydney, Biennale of Sydney, Sydney, 2018, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Fiona Gruber, "Only Connect," The Australian, 9 June 2012.

- ^ Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Artistic Director Foreword: https://www.biennaleofsydney.com.au/about-us/history/2008-2/

- ^ Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, “Revolutions forms that turn: the impulse to revolt,” in 2008 Biennale of Sydney: Revolutions—Forms That Turn, exhibition catalogue, Biennale of Sydney and Thames & Hudson, Sydney and Melbourne, 2008, pp. 30–33.

- ^ Christov-Bakargiev, “Revolutions,” p. 33

- ^ Kataoka, p. 10

- ^ The argument for spending money on a catalogue rather than on Ai Wei Wei has already been made in Gina Fairley, “Review: 21st Biennale of Sydney,” http://visual.artshub.com.au/news-article/reviews/visual-arts/gina-fairley/review-21st-biennale-of-sydney-255382

- ^ See 2008 Biennale of Sydney and 20th Biennale of Sydney: The Future is Already Here—It’s Just Not Evenly Distributed, edited by Stephanie Rosenthal, exhibition catalogue, Biennale of Sydney, Sydney, 2016.