Framing the major exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia is a display of works from the collection touching on sovereignty and colonisation grouped under the title Occupied Territory. This exhibition began in July so precedes the opening of AGSA’s exhibition for Tarnanthi. Here among works by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal artists hangs Russell Drysdale’s Mullaloonah Tank (1953), a portrait of four Aboriginal people, in which a curtain as backdrop propped up like a canvas appears to shield or separate the group from the country they are standing in. In this painting, as in the works of earlier Australian art by Yosl Bergner and Ray Crooke, portraying Aboriginal people as refugees and outcasts on their own land, the prejudice and sense of exclusion is palpable. Not so Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, which brought together a notable crush of Aboriginal people to North Terrace for the opening at AGSA and other venues across the city of Adelaide, with a raft of different perspectives and languages represented, including previously hidden words and concepts (also embedded in the project titles) to educate and enthral audiences.

Tarnanthi is a city-wide event, an art fair at Tandanya for over forty art centres, a major exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia, including over two hundred artists, plus twenty-six exhibitions around the city with many more artists. The venues and media range widely from night-time projections on the Target Centrepoint Wall and at FELTdark to Clay Stories at the Jam Factory’s Seppeltsfield Gallery in the Barossa Valley, the large South Australian artists group show Our Mob at the Festival Centre, artists of the Ngaanyatjarra lands at praxis ARTSPACE and Tjukurpa Stories at Hahndorf Academy. There was a day-long Panpa-panpalya (ideas forum), many talks, an afternoon of celebrations at Port Adelaide, smoking ceremonies, dancing and music, performances and stories. Stan Grant opened the exhibition at AGSA, comparing his experiences of Lake Mungo and the Sistine Chapel to come to a definition of art as not just something on the wall but “something that really lives inside us.”

First staged in 2015, and with secure sponsorship from BHP now to be held annually until 2021, this ambitious festival curated by AGSA’s Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Nici Cumpston seeks to round up Indigenous art-making from across the country, not in the form of the tightly curated Indigenous triennials at the National Gallery of Australia but in a more open exploratory fashion to initiate and encourage individual artists as well as those from communities and art centres from across Australia. Such projects may develop over many years thus having a lasting impact on the lives of the makers and their audiences. It is a complicated dance, as such variety and group agency involving art as social work or what could be called relational aesthetics is a large part of its performative potential. The art is never just a static presence on the wall separate from lived experience but is a means of providing income for communities, an affirmation of identity and the means through which stories can be refreshed and passed on.

Exhibitions of Aboriginal art can be very didactic or documentarian, teaching and informing about culture or relating the adverse impacts of European settler culture which can make the experience for the viewer something of an endurance or sombre reckoning. Can we, as a largely non-Indigenous viewing public, get through this wall of difference, and not just observe, but embed ourselves in a different worldview and experience? Tarnanthi answers this question in many ways, by the presence of many artists during the festival, and the exploratory and unpredictable nature of many of the works of art on show, to support creative engagement.

The inclusion of many different media beyond painting highlights the ongoing development and extension of Aboriginal culture and audience receptivity to new forms of contemporary art, often involving installation and screen-based media. This has provided artists with the opportunity to make work of size and spectacle. Reko Rennie’s OO_AR, a video projected on three large screens with Nick Cave soundtrack commemorates his grandmother’s life and removal from her family with an extravagant spectacular gesture. He buys a Rolls Royce, paints it up, drives it to Kamilaroi country near where she was born, draws circles on the land, drives away again. He has a photo of his grandmother Julia with him as a child on the dashboard. Is he the black Shaun Gladwell?

Archie Moore’s work Whipsaw at Fontanelle at Port Adelaide looked back to a replica of his grandmother’s house, with its rusted corrugated iron walls and dirt floor, first made for the 2016 Biennale of Sydney, where it was controversially sited at Bennelong Point.. At Fontanelle in the former Port Adelaide post office building, it is more like an enclosed, windowless shed, partly filled with the haze of drifting smoke (from a machine) and a soundtrack of wheels, fire and water to create a space of reverie and reflection but also uncertainty about the worlds beyond the walls.

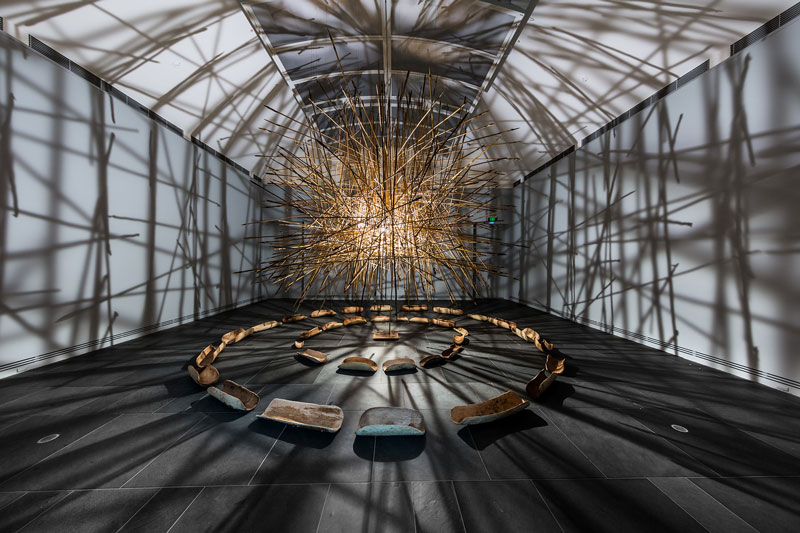

The major Tarnanthi exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia was focused on the Anangu Pitjanjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands. Works about the nuclear bomb tests at Maralinga included The Kulata Tjuta Project, a large number of spears suspended over a big circle of coolamons. The spears from this project in the last Tarnanthi were suspended like a threatening cloud of hail, this year it was more like an explosion. This installation was introduced by paintings on flourbags with symbols and inscriptions asserting sovereignty, alongside maps of Australia and videos of people talking about Maralinga. “We try not to be resentful” says one man.

Spears were also a centrepiece of Kaiki and Taralyi a project and exhibition at Tandanya led by Narrindjeri Major Moogy Sumner which involves the ongoing reclamation of tradition and bringing old ways into the present by re-enactment and recreation. The eighteen spears here were made by Sumner of reeds and seem impossibly light and delicate while another eighteen made of glass by Jessica Loughlin are superbly fine with their engraved lines and glass tips. Each represent the eighteen clans of the Ngarrindjeri nation. The accompanying works by James Tylor and Damien Shen felt more provisional as newly learnt crafts skills applied to making traditional weapons made from raw materials. It felt as if they were just at the beginning of something, as does the video by Charlotte Sumner filmed in the landscape where the artefacts were made.

At the Santos Museum of Economic Botany where relationships between people and plants are always in focus, an exhibition showed how string made mostly from kurrajong bark is an enduring feature in Yolgnu lives. So there were examples of string figures (cat’s cradle) being made by Wandjuk Marika in a video, actual string figures pinned onto boards collected by Frederick McCarthy in 1948 and borrowed for the show from the South Australian Museum, and two sets of etchings of string figures, one lot intaglio printed in 2010 by Grey Lady Press, and the others relief printed in 2013 by Basil Hall. But the best thing was the actual strong new shining string made in 2017 by different Yolgnu people presented on rather lovely wooden spindles. Photographs of the string being used in contemporary daily life was the missing element here.

At the South Australian Museum the exhibition Ngurra: Home in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands curated by Glenn Iseger-Pilkington covered many aspects of life through photography, audio and moving image work as well as T-shirts, everyday objects cast in soap, paintings, Tjanpi weavings, motorbikes and cars. Based around the idea of explicating ngurra which means “home,” the show was framed as an implicit riposte to the claim of living on homelands being a “lifestyle choice” as described by Tony Abbott in 2015. Immersive and absorbing, interactive and busy, the exhibition provided many entry points. Outstanding was a 2004 painting by Coiley Campbell and a wonderful big tree by the Tjanpi Desert Weavers.

Then there was Barangaroo Ngangamay at the Migration Museum, photographs and elements of a site-specific work made by Genevieve Grieves and Amanda Jane Reynolds for Barangaroo Reserve in Sydney, in homage to a Cammeraygal woman who lived there during the British invasion. Here the immense softness and big healing spirit of women’s voices doing women’s business was a mesmerising body of work to encounter, while nearby Bush Mechanics, a show initiated by the Motor Museum and installed in a corner of the Drill Hall contained the antic energy of young men in excerpts from the eponymous TV series and the actual battered Holden EJ Special Station Sedan, the roof of which collapsed and was then removed and turned into a trailer without wheels.

The strength of Aboriginal women was in full force at ACE Open in the women’s group show Next Matriarch where Hannah Brontë’s stunning digital work of morphing black women as rap artists dominated the space in an extraordinarily powerful and confronting way. Kaylene Whiskey paints lively humorous images of women as super-heroines and pop-cultural icons, while Ali Gumillya Baker’s sovereignGODDESSnotdomestic uses a mixture of severity and queenliness to commemorate the lives of the women in her family rejecting a history of servitude. Versatile performance artist and designer Nicole Monks was included here as well as in Tarnanthi at the Art Gallery and at the Jam Factory where her furniture using kangaroo pelts turned chairs into thrones. At the Gallery We Are All Animals/Sheemu her video and costume marked her live performance combining emu feathers and sheep’s wool, animals associated with Aboriginal and settler culture, to reconcile aspects of a common material heritage and culture.

Also at the Jam Factory in Yirrb – Together the mother-daughter team from Waringarri Arts Jan and Peggy Griffiths show ceramic dishes and landforms with strong narratives. Speaking of ceramics, a body of work made with great expertise and feeling by Pepai Jangala Carroll and Derek Jungarrayi Thompson of Ernabella Arts, on exhibition at AGSA also possessed a strong Chinese influence while responding to country and ceremony.

At the entrance to the exhibition at AGSA, it was confronting and arresting to encounter a large projection of black and white archival footage of near-naked Aboriginal men and women dancing and singing flanked by a colour film of clouds on an adjacent wall. In front of the projections are Wanupini Larrakitj, wooden memorial poles with clouds painted on them and halfway down the stairs and nearby are Mokuy, spirit figures, both made by Nawurapu Wunungmurra at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre. My immediate reaction to the film footage was to recoil at what is possibly culturally inappropriate – showing images of dead people. But, framed as part of a contemporary art installation, it came with Indigenous agency and permission to observe and admire the abandonment and physicality of these people from another era. The projections, devised by Ishmael Marika as part of the The Mulka Project at Yirrkala, clearly inspired connections across time. As he states in the catalogue, “Watching the knees of my ancestors I match the rhythms of the past with the songmen of today linking Mari Guthara, grandfather to grandson.” This reminded me of the The Documentary of Dr G. Yunupingu’s Life, recently screened at the Adelaide Film Festival, which included footage of the funerals of Dr G’s mother and father where the singing and dancing was especially moving, showing bent knees, impossibly thin calves and compelling energy.

Further into the exhibition, the collaborative video by Mundatjngu Mununggurr and Gutingarra Yunupingu for The Mulka Project called Yuta Mulkurr, New Minds, is composed of short takes of different images of country, weather, the sky and the peripheries of community life. Later in the day when I looked at the clouds I felt differently towards them as if I was closer to them, or able to see them with new eyes.

A room of black and white photographic portraits of mature Tasmanian Aboriginal men made in Launceston between 2013 and 2015 called Saddened Were The Hearts Of Many Men by Ricky Maynard is a response to American photographer Walker Evans’ project Let Us Now Praise Famous Men which documented the lives of impoverished tenant framers during the Depression. The faces that you see in Maynard’s photographs, and the men and women in the photographs by Robert Punnagka Fielding of APY Elders, and in the catalogue of Yarrenyty Arltere Artists by non-Aboriginal photographer Tony Kearney also convey bitter and hard life experiences. These intimate portraits of Aboriginal people assert fortitude and survival while replicating the mixed blessing of anthropological portraiture that while reviled as inhuman and intrusive has been important in recent land claims and research into family histories. The photographs of artists in the catalogue in general are also appealing in their honesty and directness.

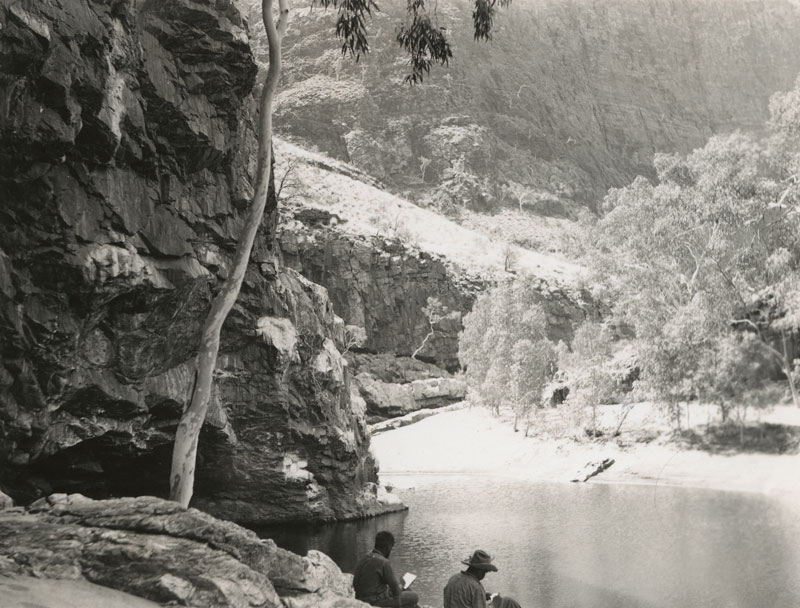

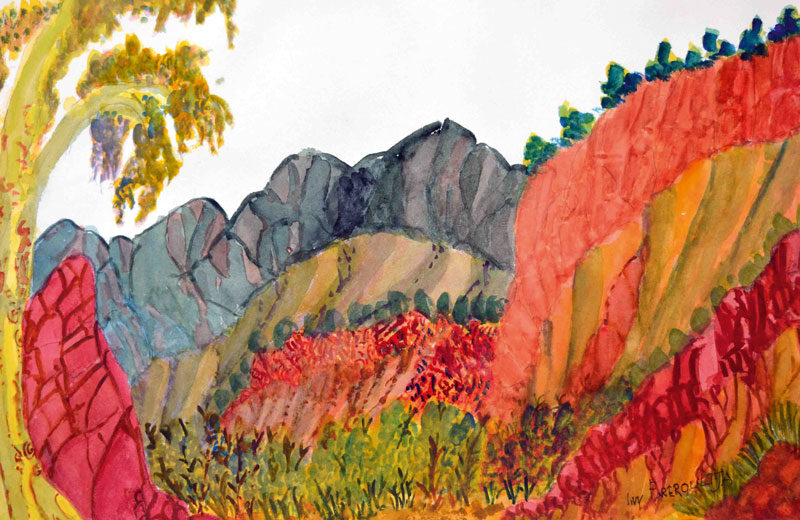

Other powerful works were from a project initiated by non-Aboriginal artist Tom Nicholson that examines the black and white photographs in the Battarbee Collection at the South Australian Museum taken on painting trips by Rex Battarbee and Albert Namatjira at various sites in Central Australia. Called What If This Photograph Is By Albert Namatjira? the project juxtaposes photographs and paintings in irregular configurations that need close viewing. The seventeen artists involved from Iltjara Ntjarra/Many Hands Arts Centre in Alice Springs each made watercolour paintings in the style of the Hermannsburg School of Namatjira as they have been doing for years, but somehow the paintings are given more structure and invigorated by juxtaposition with the photographs. As Nicholson point out in his essay in the catalogue quoting one of the senior painters, Mervyn Rubuntja, it is gap between the photograph and the painting that drives the impetus and inspiration for the work.

Nearby, the work by Bob Burruwal and his wife Lena Yarinkura from the Maningrida region of two tableaux of a Namorrorddo story about spirit beings was presented with very little story in a darkened space with a soundtrack that included heart beats and whistling. It enchanted the space, and if you stopped and observed closely the animation and vitality of the figures included a child dog and its parent. I was standing still in the space in a spotty shirt, and when I moved a woman shrieked because she had not seen me in the darkness. That was really quite spooky. You have to read the story in the catalogue.

A work from the APY Lands, sporting similar characters was the Indulkana spaghetti western Never Stop Riding, a short wild ride with Aboriginal cowboys in R.M. Williams gear. That chapter of Aboriginal men’s history was also present at the Adelaide Central School of Art Gallery exhibition Abstracted Muster, a collaborative charcoal drawing by Mervyn Street and non-Aboriginal artist Robert Hannaford, which temporarily covered the walls with a muster of animated cattle, horses and stockmen. Back at AGSA, Jimmy Pompey and Eric Kunmanara Barney’s delightful bronze animals also draw on the close knowledge of stock animals among an earlier generation of Aboriginal people.

.jpg)

Not dissimilar to the working life of Abstracted Muster, amongst the most unusual and striking works at AGSA for me were the paintings by Nyaparu George Williams working at Spinfex Hill Studios in Port Hedland in Western Australia. Portraits from memory of the men he had known, working on stations and in mining, whom he describes as drifters, mineral men and horse men. Here, they are drawn in thin scratchy black marks, then coloured vividly and surrounded by freshly painted landscapes in virulent hues to create an all-over intense charge. Maybe it is the charge of memory. There is a fresh intensity and necessity about these works by an artist who has for many years been creating images of the Pilbara and the Kimberley.

It is important to mention the two colourful and complex giant collaborative paintings from the APY lands, the men’s one and the women’s one. And something to take away and reflect upon is the explanation of the qualities of Kunmara (Gordon) Ingkatji who died at the start of the men’s painting being made and to whom it is dedicated. The artists’ statement says that he was: “a highly principled man and lived by the values of unconditional giving/generosity (munytja); always being friendly, happy (pukulpa); taking seriously his role as teacher (nintilpai); holding law strong and being a strong man (wati kunpu) and never forgetting to love (mukulya).”